IT USED TO BE that our consumption was tightly controlled by a few big corporate beasts. We were their captive audience; they knew who we were, our appetites seemed predictable enough and so they all fed us much the same thing. Now however, they’ve emerged blinking into a new environment populated by many different species, each of which seems to want different things… Survival in this new terrain, however, is not of the fittest but of those with the best fit with their environment. More than anything, it depends on finding something you feel strongly about and cultivating it. Find a clear niche and you make it fantastically easy for people to find you. Fail to do so and you risk ending up on the list of endangered species.1

James Harkin, from ‘Niche: Why the Market No Longer Favours the Mainstream’, 2011.

Though journalist James Harkin’s theory sits in the context of economics, it could be applied to the rise of niche fragrances we are currently witnessing. While large beauty corporations like Coty, Givaudan or International Flavors and Fragrances (IFF) continue to thrive, small ‘niche’ companies have proven to be highly successful competitors. Le Labo Fragrances, a boutique fragrance brand based in New York and London, has expanded into a business with over $US20 million in annual retail sales since it was founded in 2006. In October 2014, the company was purchased by cosmetics giant Estée Lauder2, indicating the increasing importance of independent brands even in a mainstream market. This once small sector of the industry has experienced exponential growth, begging the question: has niche grown too big for its own niche?

By definition, a niche fragrance company is characterised by an independent and smaller production scale, as well as a select number of specialist stockists as opposed to the department and chain stores of its mainstream competitors. This more artisanal approach towards production, means that niche scents often – although not always – carry a higher price tag, adding to the notion of a more exclusive, and some would argue higher quality, product.

A recent podcast by the fragrance website Basenotes, ‘The Art Perfumes Formerly Known as Niche’3, highlights the rise of niche perfumes in the fragrance market. In the discussion perfume marketer Callum Langston-Bolt states: ‘Niche is a place where you are able to do more unusual things. You’ve got more room so the perfumer is able to make this kind of fragrance, they can make something new or bizarre’. To which Lizzie Ostrom, founder of the olfactorial events company Odette Toilette, adds, ‘It’s the marketing, it’s a craving for the way that niche perfume markets itself and is much more sophisticated about telling a story that people find compelling and that offers them another way into the fragrance.’

Like fashion, scent is symbolic, offering a way of communicating ourselves as individuals and social beings. As such, choosing and purchasing a fragrance is a highly selective process, since a signature scent can be seen as the ultimate accessory and form of identification. Applying fashion theorist Carol Tulloch’s concept of style narratives, that ‘the process of self-telling, that is, to expound an aspect of autobiography of oneself through the clothing choices an individual makes,’4 one could refer to scent narratives. This creation of identity plays an essential part in the actions of the fragrance consumer: a mass market perfume is unlikely to satisfy a customer wanting to identify themselves as unique or fashion-forward. Just as in fashion, no one wants to be caught wearing the same thing as those around us, and it is this consumer desire to be different that niche fragrance companies capitalise on. Harkin’s thesis furthers this notion, outlining ‘a world in which no size fits all, and in which anyone who tries to be all things to everyone ends up as nothing to anyone.’5

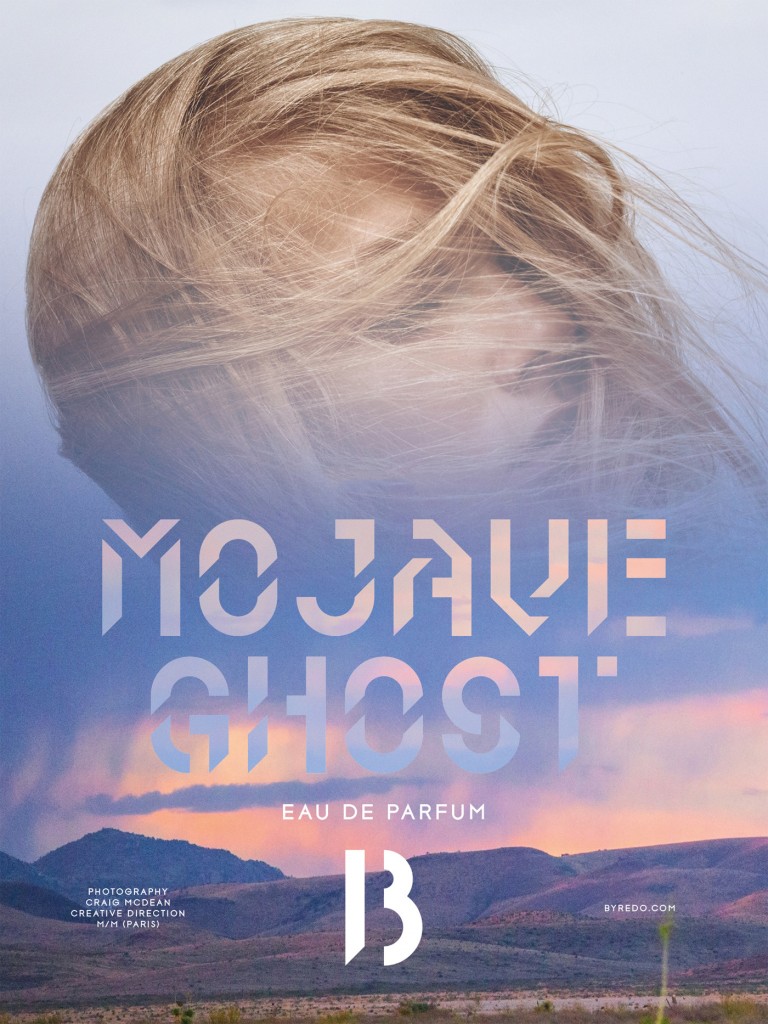

Claiming a stake in the world of niche fragrances means offering a customer authenticity over availability. Whether a company draws on their heritage, like London’s Penhaligon’s, offers highly artistic campaigns, like those of Byredo, gives perfumers carte blanche, like Editions de Parfum Frédéric Malle, or simply goes for an unconventional concoction smelling of blood, sweat, saliva and sperm à la État Libre d’Orange, the notion of rarity and exoticism is crucial. These niche fragrance companies craft their fragrances to appeal to a consumer desire for individuality.

In contrast to fashion, concerns of wearability and overexposure are less significant for fragrance. If a perfume bought from your local drugstore is akin to fast fashion, then niche fragrances are the haute couture of scent. However, the higher price point, limited availability and complex product narratives of niche fragrances do not distance or exempt them from fragrance trends or commercial profit. As a result, niche fragrances can be inspired by anything from blood types (Blood Concept) to New York City districts (Bond No. 9). The rise in niche fragrance into larger-scale businesses, of which Le Labo is a good example, challenges the authenticity of the market. As the fragrance industry continues to grow, do these brands run the risk of becoming mainstream?

One could argue that simply because a niche fragrance brand gains mainstream attention does not mean it has ‘sold out’. For if we define niche by a perfume brand’s production methods, boutique retail positioning and focus on craftsmanship; as long as they retain these values, the product arguably still retains its credibility. Even if rising sales figures threaten brand overexposure, as long as consumers are in search of an individually crafted and highly authentic product, niche fragrance companies will continue to thrive and offer scents that reside in the realms of the extraordinary.

Carla Seipp is a freelance fashion, arts and fragrance journalist.

Harkin, James. 2011. Niche: Why the Market No Longer Favours the Mainstream. London: Little, Brown. p. 5-6 ↩

‘Le Labo Was Just Acquired by Beauty Giant Estee Lauder’, by Adele Chapin, October 15, 2014. http://racked.com/archives/2014/10/15/estee-lauder-le-labo.php ↩

Tulloch, Carol 2010. “Style-Fashion-Dress: From Black to Post-Black”. Fashion Theory 14(3). p 361-86. In: Fashion and Cultural Studies. 2012. Kaiser, Susan. London and New York: Berg. p. 6-7 ↩

Tulloch, Carol 2010. “Style-Fashion-Dress: From Black to Post-Black”. Fashion Theory 14(3). p 361-86. In: Fashion and Cultural Studies. 2012. Kaiser, Susan. London and New York: Berg. p. 6-7 ↩

Harkin, James. 2011. Niche: Why the Market No Longer Favours the Mainstream. London: Little, Brown. p. 4 ↩

État Libre d’Orange website: http://www.etatlibredorange.com. ↩