‘We are never neither really someone else, nor really the same person.’

– Philippe Lejeune, On Autobiography, 1989.

IN ANDRÉ BRETON’S NOVEL Nadja, first published in 1928, the author describes an unconventional woman who embodies the principles behind Surrealist art: a ‘disinterested play of thought’, the practice of ‘psychic automatism’ and the search for the ‘marvelous’ in everyday life.1 Italian-born French couturière Elsa Schiaparelli (1890-1973) was a real-life Nadja who incarnated these ideals in an ambiguous way. Like the persona of Paul Poiret, hers too was built around her status as an artist rather than a dressmaker. Ironically, this promotional strategy was achieved through refined commercial acumen: by associating themselves with art rather than business they imbued their work with a magical aura that became key to their commercial success. The designer’s autobiography, Shocking Life (1954), wove together her personal and professional contradictions and secured a legacy after her maison had ceased to exist.

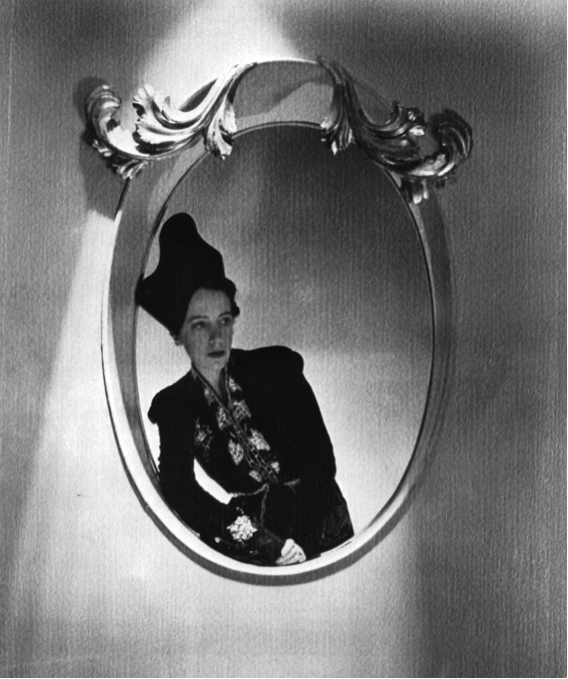

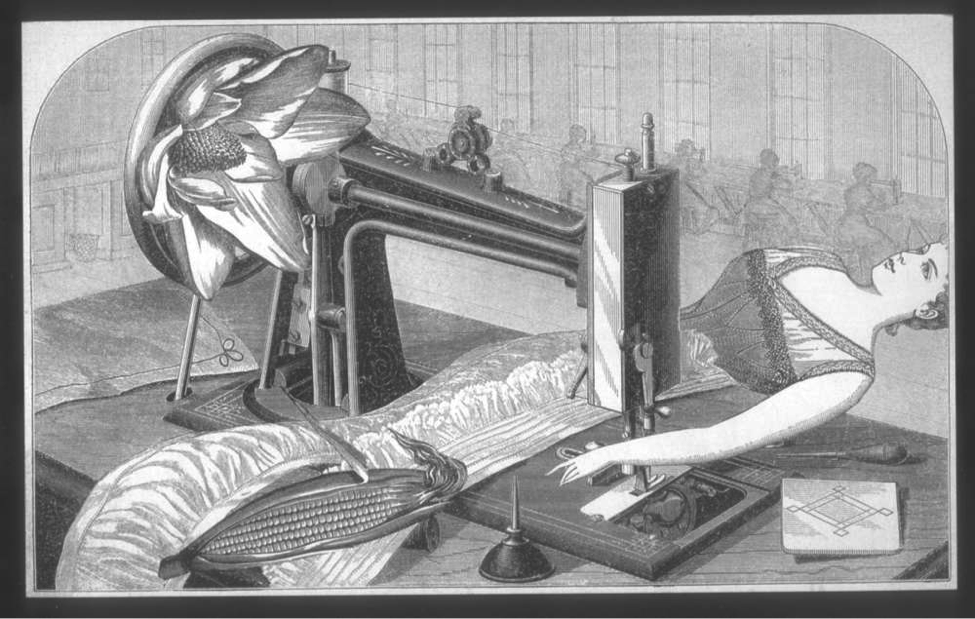

A recurring theme in the text and in her work is that of metamorphosis. In the book, Schiaparelli employed rhetoric strategies to shape the narrator as an ever-changing self, impossible to pin down. As in her designs, where she subverted taste and functionality of a garment – an insect became a button, a shoe inspired a hat, a trompe l’œil effect turned a jumper into a shirt. A key word in the Surrealist vocabulary, metamorphosis bears strong associations with transformation, mystique, and duality. In this way, Schiaparelli’s autobiography is a literal mirror to the Surrealist themes in her dress designs, navigating the blurred lines between art and fashion, history and fantasy, political engagement and studied indifference in the construction of her public persona.

The title Shocking Life alone suggests multiple readings. ‘Shocking’ refers to her life, one of excitement, privilege and excess; it also references ‘Shocking Pink’, the colour she created, which acts as a synecdoche for her provocative designs; finally, it underscores her commercial success by echoing the name of the fragrance she launched in 1937. But as critic Judith Thurman observes, ‘what is most shocking about Schiaparelli […] is her obscurity.’2

The obscurity that Thurman pinpointed is the key feature of Schiaparelli’s protean and self-constructed persona in Shocking Life. Throughout the book, the designer alternatively refers to herself as ‘I’, ‘she’ and ‘Schiap’. In the foreword her personality is presented as inherently contradictory: ‘She is unpredictable but, in reality, disarmingly simple. She is profoundly lazy but works furiously and rapidly […] She is generous and mean […] she both despises and loves human beings […] If she is charming she can also be the most hateful person in the world.’ The effect is a constant mirroring of fragments of her own persona, which makes it difficult for the reader to see beyond the theatricality of rhetoric. While personal and historical accounts abound, the misadventures, the travels, the economic success, the troubled family life and the observations on World War II seem to follow one another for the sake of spectacle rather than reflection, to dazzle readers rather than draw them in. Schiaparelli’s technique follows the refusal of logic, rationality, clarity and order advocated by Bréton in his 1924 Surrealist Manifesto, a text that was in turn influenced by Freud’s studies on dreams and the unconscious. Schiaparelli’s focus in the text is the surface: of the events, of her self, of her persona.

Much like Paul Poiret, Schiaparelli resorts to the romantic myth of the misunderstood artist. She describes her youth as a constant struggle against the expectations of her family; she was ‘revolutionary and stubborn’, ‘far too imaginative’ and ‘ultra-sensitive’, looking for a creative outlet to express herself. Her view of fashion is summarised in the following passage:

‘Dress designing, incidentally, is to me not a profession but an art. I found that it was the most difficult and unsatisfying art, because as soon as a dress is born it has already become a thing of the past […] The interpretation of a dress, the means of making it, and the surprising way in which some materials react – all these factors, no matter how good an interpreter you have, invariably reserve a slight if not bitter disappointment for you. In a way it is even worse if you are satisfied, because once you have created it the dress no longer belongs to you. A dress cannot just hang like a painting on the wall, or like a book remain intact and live a long and sheltered life.’

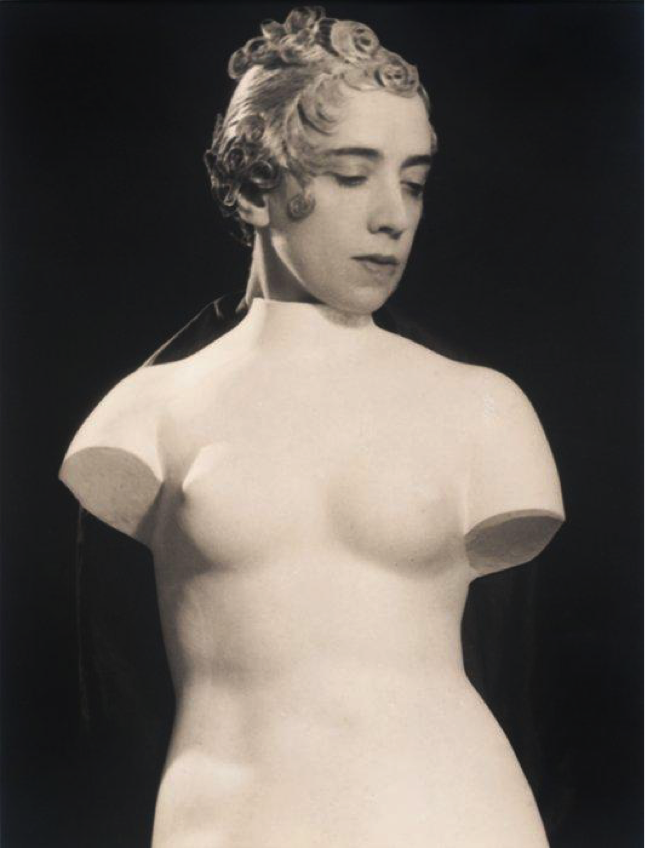

Schiaparelli expresses dissatisfaction with the commercial nature of fashion while also drawing from Surrealist rhetoric to describe to her creative process as ‘a dream’. The issues of originality, fantasy, and authorship that emerge echo depictions of fashion, femininity and sewing machines in Surrealism at large. Her use of terms from the artistic discourse, with which she was intimately familiar, also elevated the credibility of her persona and added an aura of exclusivity to her brand. The Surrealist fascination with everyday objects and articulation of the self as unstable or ‘decentered’3 meant that fashion became an important site for the exploration of identity. Many Surrealists gravitated around fashion working as photographers, illustrators and designers, and did in fact embrace its commercial nature. Rather than to prove herself to them, however, Schiaparelli had to prove herself to mass audiences, which generally considered art and fashion as very distinct realms.

In reality, Schiaparelli engaged with the commercial nature of fashion just as well as her rival Coco Chanel, who famously dismissed her as ‘that Italian artist who makes clothes’. Not only did she promote her ‘hard chic’ silhouette to the masses by associating her brand with Hollywood darlings like Marlene Dietrich, Greta Garbo and Katharine Hepburn, but she was the first designer to lend her creations out as a promotional strategy to often photographed Parisian women such as French actress Arletty and socialite Reginald Fellowes.

Schiaparelli’s business acumen was confirmed by the launch of her fragrance Shocking, whose bottle was designed after the body shape of Mae West, then one of the most celebrated Hollywood actresses. As fashion historian Colin McDowell observes, her maison was financially secure thanks to the licensing of nail varnish, underwear and menswear, but also less fashionable goods such as mattresses and shower curtains.5

Omissions abound in Schiaparelli’s autobiography, where silences matter as much as her dramatic stories. The designer glosses over her controversial political connections during World War II and constantly downplays the role of her less-than-glamorous business endeavours. It is the space between what is said and unsaid that allows her to craft a mythical persona. Like Nadja, who seeks to crash bourgeois values through her clothing and embodies Breton’s view of irrationality as the essence of femininity, Schiaparelli thrived on contradiction; her public persona offered her a consistent strategy to avoid the implications of her incongruence.

Alex Esculapio is a writer and PhD student at the University of Brighton, UK.

A. Bréton, The Manifestoes of Surrealism, University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, 1972. ↩

J. Thurman, “Mother of Invention,” The New Yorker, 27 October 2003, p.58. ↩

C. Evans, “Masks, Mirrors and Mannequins: Elsa Schiaparelli and the Decentered Subject”, Fashion Theory, Volume 3, Issue 1, 1999, pp. 3-32 ↩

R. Martin, Fashion and Surrealism, New York, Rizzoli, 1987. ↩

http://www.businessoffashion.com/articles/education/elsa-schiaparelli-1890-1973. ↩