IN NO ONE ARTICLE of dress is the ultra-feminine psychology more apparent than in the hat.

***

In ordinary life we have the well-known fact of the lasting beauty that shines in such severe simplicity as the white face-bands of the nun, or in many of the neat and unchanging caps worn by Puritans, Quakers and others. We even know, in that remote shut-off compartment of the mind wherein we keep our articles of faith, that ‘Beauty unadorned is adorned the most.’

Beauty, however, is far from our thoughts. With serene unconscious fatuous pride our women put upon their heads things not only ugly, but so degradingly ridiculous that they seem the invention of some malicious caricaturist. In ten years’ time they themselves call them ugly, absurd, and laugh at their misguided predecessors for wearing them. If honest and long-memoried, they even laugh at themselves, saying: ‘How could we ever have worn those things!’ But not one of them stops to study out the reason, or to apply this glimmer of perception to the things she is wearing now.

Any book on costume shows this painful truth – that neither man nor woman has had any vital and enduring beauty sense; and further that while man has outgrown most of his earlier folly, woman has not.

There is today no stronger argument against the claim of Humanness in women, of Human Dignity and Human Rights, than this visible and all-too-convincing evidence of sub-human foolishness.

In other articles of costume there have always been certain mechanical and physiological limitations to absurdity. In hats there are none. So that the wearer is able to carry it about, so that in size it is visible to the naked eye, or capable of being squeezed through a door – with these slight restrictions fancy has full play, and it plays.

The designer of women’s hats (let it be carefully remembered that the designers and manufacturers are men) seem to sport as freely among shapes as if the thing produced were meant to be hung by a string or carried on a tray, rather than worn by a human creature. There is a drunken merriment in the way the original hat idea is kicked and cuffed about, until the twisted misproportioned battered thing bears no more relation to a human head than it does to a foot or an elbow.

The basic structure of a hat is not complex. Its ancestry may be traced to the hood, coif, cap, the warm cloth or fur covering, still shown in ‘the crown’; and to the flat spreading shelter from the sun, now remaining in ‘the brim.’ In simplest form we find these two in the ‘Flying Mercury’ hat, a round head-fitting crown, a limited brim. The extreme development of brimless crown is seen in the ‘night-cap’ shape worn by the French peasant, the ‘Tam O’Shanter’ of the Scotchman, the ‘beretta’ of the Spaniard, or the ‘fez’ of the Turk. The mere brim effect is best shown in the wide straw sun-shield of the ‘Coolies.’

Among the Welsh peasant women we find the crown a peak, the brim fairly wide; among priests, Quakers, and others, we find a low crown and a flat or rolled brim; in the ‘cocked hat’ the brim is turned up on three sides; the ‘cavalier’ turned his up on one side and fastened it with a jewel or a plume. Among firemen and fishermen the brim is widened at the back to protect the neck from water.

There is room for wide variation in shape and size without ever forgetting that the object in question is intended to be worn on a head. But our designers for women quite ignore this petty restriction or any other. I recall two instances seen within the last few years which illustrate this spirit of irresponsible absurdity.

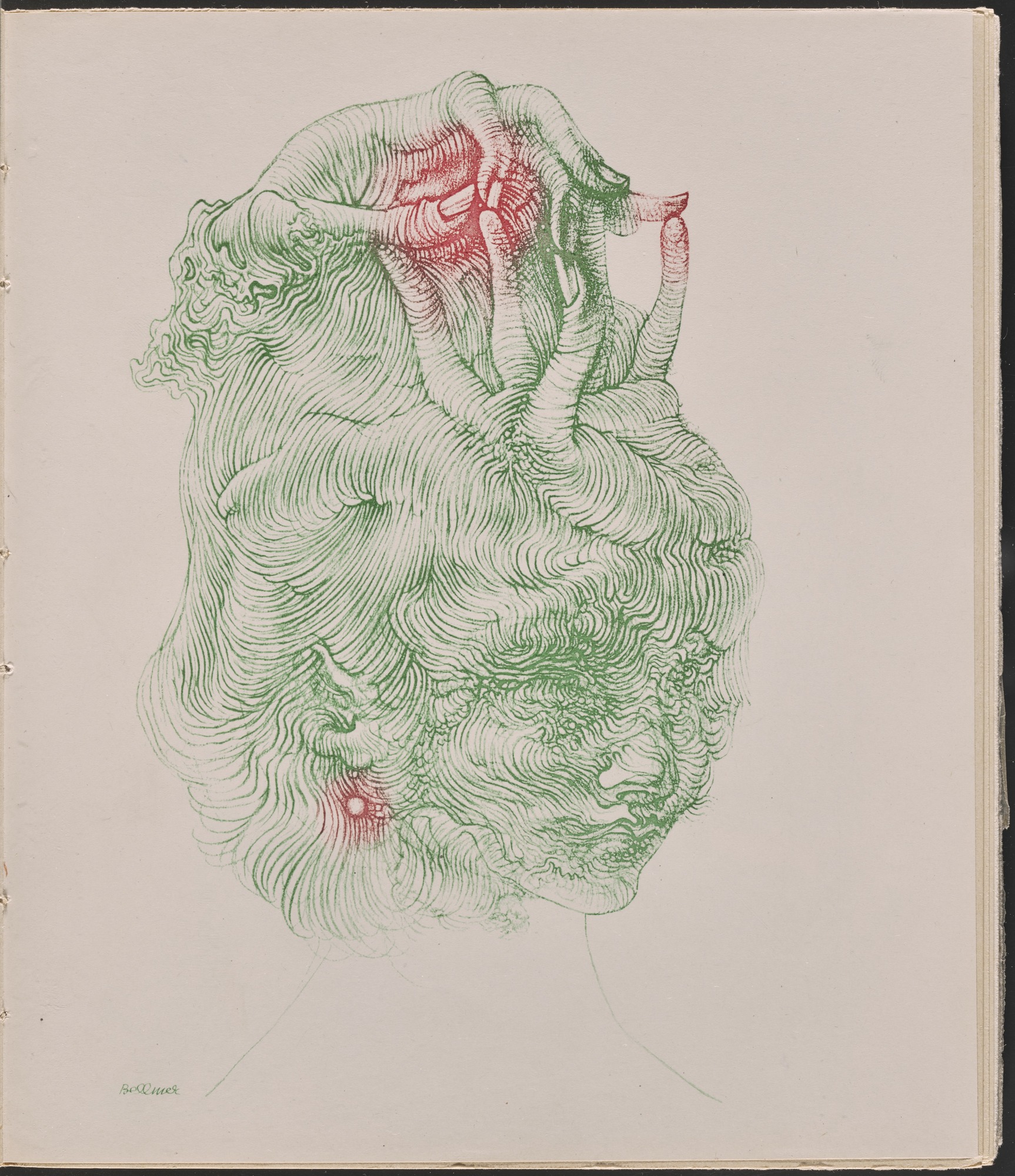

In one case the crown was lifted and swollen till it resembled the loathsome puffed-out body of an octopus; and this distorted bladder-like object was set on an irregular fireman’s brim – to be worn side-ways.

For forthright ugliness this goes far, but here is one that passes it for idiocy: Figure to yourself a not unpleasing blue straw hat, with a bowl-shaped crown, setting well down on the head, and a plain turn-up brim about two inches wide. Then a grinning imbecile child gets hold of it. With gay grimaces he first cuts the brim carefully off, all of it, leaving the plain bowl. Then, chattering with delight, he bends the brim into a twisted loop, and fastens it across the ‘front’ of the inverted bowl, about halfway up. There it sticks, projecting like a double fence, serving no more purpose than some boat stranded by a tidal wave halfway up a hillside. And this pathetic object was worn smilingly by a good-looking young girl, with the trifling addition of some flat strips of blue velvet, and a few spattering flowers – all as aimless as the stranded brim.

Five years ago it was customary for women to wear hats not only so large in brim circumference as to necessitate tipping the head to get through a car door, but so large in crown circumference as to descend over the eyebrows, and down to the shoulders. These monstrosities were not ‘worn’; they were simply hung over the bearer as a bucket might be hung over a bedpost. And the peering extinguished ignominious creatures beneath never for one moment realised the piteous absurdity of their appearance.

Yet it is perfectly easy to show the effect by putting the shoe on the other foot – that is, the hat on the other head. Imagine before you three personable young men in irreproachable new suits of clothes, A., B., and C. Put upon their several heads three fine silk hats, identical in shape and style, but varying in size: upon A., at the left, a hat the size of a muffin ring, somehow fastened to his hair; upon B., in the middle, an ordinary sized hat, fitting his head perfectly; upon C., at the right, a huge hat, a hat which drops down over his ears, extinguishes him, leaves him to peer, with lifted chin, to see out from under it in front, and which hangs low upon his shoulders behind. Can any woman question the absurdity of such extremes – on men?

When some comic actor on the vaudeville stage wishes to look unusually absurd, he often appears in a hat far too large, a hat which, seen from the back, shows no hint of a neck, only that huge covering, heaped upon the shoulders. In precisely such guise have our women appeared for years on years, with every appearance of innocent contentment – even pride. They had no knowledge of the true proportions of the human body, the ‘points’ which constitute high-bred, beautiful man or woman. They did not know that a small head, one eighth the height of the person, was the Greek standard of beauty; that a too large head is ugly, as of a hydrocephalic child, or of some hunched cripple whose huge misshapen skull sits neckless, low upon his shoulders. They deliberately imitated the proportions of this cripple. Seen from behind a woman of this period was first a straight tubular skirt, holding both legs in a relentless grip, as of a single trouser; then a shapeless sack, belted not at the waist, but across the widest part of the hips (a custom singularly unfortunate for stout women, but accepted by them unresistingly); and then this vast irregular mass of hat, with its load of trimming, as wide or wider than the shoulders it rested on. In winter they would add to this ruthless travesty of the human form by a thick boa, stole, or tippet, crowded somehow between shoulders and hat, so that you could see nothing of the woman within save her poor heel-stilted feet, the strained outline of those hobbled legs, and part of the face if you ducked your head to look beneath the overhang, or if she lifted her oppressed eyes to yours.

At present the Dictators of our garments have changed their minds and we are now for the most part given hats of the most diminutive size, whose scant appearance is ‘accented’ by some bizarre projection, some attenuated crest of pointed quill, or twiddling antennae.

What accounts for this peculiar insanity in hats? Why should a woman’s hat be, if possible, even more absurd than her other garments? It is because the hat has almost no mechanical restrictions.

When a woman selects a hat; when she tries one on, or even looks at one in a window, she sees in that hat, not a head-covering, not her own spirit genuinely carried out through a legitimate medium, but a temporary expression of feeling, a mood, a pose, an attitude of allurement.

The woman’s hat is the most conspicuous and most quickly changed code-signal. By it she can say what her whole costume is meant to say; say it easier, oftener, more swiftly. Because of this effort at expression, quite clearly recognised by the men who design hats, they are made in a thousand evanescent shapes – to serve the purpose of a changeful fancy. Did he see her in this and think he knew her? He shall see her in that and find she is quite different. Man likes variety; he shall have it.

***

If a woman wants to judge her hat fairly, just put it on a man’s head. If the hat makes the man look like an idiot monkey she may be very sure it is not a nobly beautiful, or even a legitimate hat. If she says: ‘Oh, but it is so cute on me!’ let her ask herself: ‘Why do I wish to look cute? I am a grown woman, a human being. Mine is the Basic Sex, the First, the Always Necessary. I am the Mother of The World, Bearer and Builder of Life, the Founder of Human Industry as well. My brother does not wish to look ‘cute’ in his hat – why should I?’

Women, supposedly so feminine, so arbitrarily, so compulsorily feminine, so exaggeratedly and excessively feminine, do not realise at all the true nature, power and dignity of the female sex. When they do, even in some partial degree, there will be nothing in the long period of their subservience upon which they will look back with more complete mortification than their hats.

Feminist writer and sociologist Charlotte Perkins Gilman originally published her polemic on hats, excerpted above, in 1915, as part of a series of essays in her magazine The Forerunner. It later became a chapter of her book, The Dress of Women.