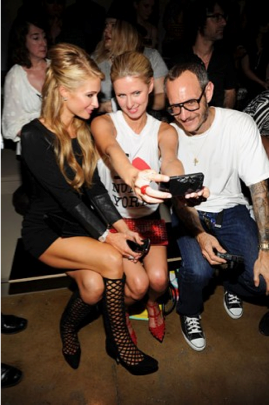

A QUICK GOOGLE SEARCH on ‘socialite’ will inevitably come up with any number of recognisable faces from twenty-first century celebrity culture. Touted by gossip magazines and tabloids like The Daily Mail, Hello and Who, the term is rarely used with flattering connotations. Paris Hilton, Nicole Richie, Tara Reid, Blake Lively and Kim Kardashian, among many other women, are just some of the wayward celebrities that nowadays are deemed as ‘socialites’, suggesting that, despite the attention they receive as objects of public fascination, their activities lack substance and are therefore trivial and excessive. With this in mind, it’s interesting to note the shift in perception that the term ‘socialite’ has undergone since its historical origins and its later heyday in the social circles of New York’s upper class with the ‘ladies who lunch’.

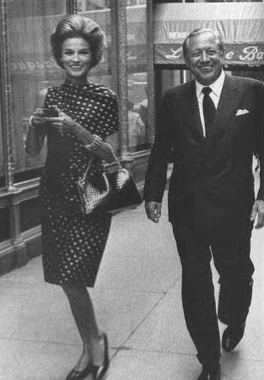

The term ‘socialite’ is a mainstay in popular culture and has its roots in the eighteenth and nineteenth century, when it referred to a woman – either a wife or mistress of nobility – who in their ceremonial title, was required to spend much of their time socialising. Additionally socialising was often necessary to their livelihood and the maintenance of their cultural footing. More recently, in the twentieth-century the notion of a socialite has become intrinsically linked with New York’s high society. Increasing wealth and culture in the city created the phenomenon of the ‘ladies who lunch’. According to John Fairchild, publisher of Women’s Wear Daily, the term was solidified in his magazine in the early 1960s (long before Stephen Sondheim’s Broadway hit), and regularly used in the social pages of WWD alongside images of upper class women. The era, which lasted from the mid-1950s until (arguably) the late-1980s, saw the elegant set of New Yorkers – millionaire wives, former models, editors and designers – frequenting Madison Avenue restaurants like The Colony, Le Pavillon, La Côte Basque and La Caravelle. The women in these establishments outnumbered the men six to one, making them prime spots for the financial and social elite to mingle frothily in designer clothes and jewellery.

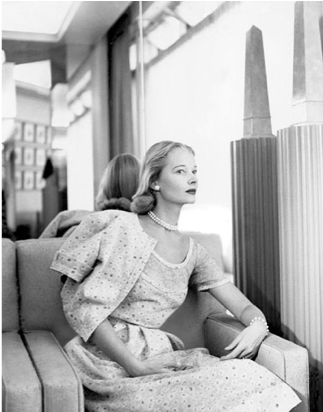

The mid to late-1950s was an opulent time, adjacent industries and cultural characters rubbed shoulders over lunch, facilitated by characters like the Duchess of Windsor, Truman Capote, Slim Keith, Babe Paley, Jackie O, Nan Kempner, Adele Astaire, Gloria Vanderbilt, Lila Wallace and Bunny Mellon, among many others. Fashion designers were also important in marking this social elite. One of the most prominent was the haute couturier Main Rousseau Bocher, with his label Mainbocher, who dressed many of these ladies who lunched, resulting in the designer’s business success corresponding closely with that of the socialite era. The designer, originally from New York, opened his couture house in Paris in 1929 under the moniker Mainbocher, after leaving his job as the editor-in-chief of Vogue Paris. In 1936 Wallis Simpson, a key figure of her generation, famously wore Mainbocher to her wedding to King Edward VIII. The dress, and the wedding – including, as it did, the King’s abdication and the elevation of a commoner to nobility – became a point of public fascination and launched Mainbocher’s American career. Following this success, the designer moved back to New York in 1940 and established his fashion house there, making Mainbocher Christian Dior’s American couture counterpart in catering for the upper class set.

In an era noted for its elegance and propriety, Mainbocher was integral to forming this notion. His dresses were strategically placed on the beautiful, wealthy and privileged and their elegant and effortless design came to mark the style of the epoch. The designer had a particularly strong affinity with the socialite CZ Guest, who accurately depicted Mainbocher’s sensibility with what her friend Truman Capote termed her ‘cool vanilla charm’.

In keeping with the style of their dresses, the sensibilities and public personas of the ladies who lunched were also demure, elegant and restrained. In his 2012 article for Vanity Fair Bob Colacello concedes that many of the ladies who lunched denied that they had participated in the activities; interior designer and millionaire wife Mica Ertegun, for instance, insists ‘I was never part of it’1, suggesting that socialising was as much about being prudent and restrained as it was about the outward projection of opulence and wealth. This act of omission might also reflect the changing role of women in society and the balancing of the workforce: the era of the ladies who lunch upheld outdated notions that its privileged women were not expected to work. This attitude arguably contributed to the decline of the era, and stands in sharp contrast with today’s society, in which it is no longer respectable for women to merely socialise, and not work.

Beyond the 1990s and into the contemporary era, ‘socialite’ has become a largely scandalous term, suggesting the type of attention-seeking party-goer so attractive to gossip magazines. Television programs like Gossip Girl (2007) and the reality shows The Simple Life (2003) and The City (2008), have succeeded in thoroughly exhausting the term as having negative connotations for those to which it is applied. This shift naturally reflects the prevalence of mass media and celebrity culture, but is also reflective of a change in our cultural taste. The bygone gatherings of Mainbocher’s ladies who lunch no longer have a place in such a society, and the sartorial values of elegant, modest glamour, so integral to the clothes which were worn at the time, have gone along with it.

Laura Gardner is Vestoj’s former Online Editor and a writer in Melbourne.

‘Here’s to the Ladies Who Lunched!’, By Bob Colacello. Published in Vanity Fair, February, 2012. http://www.vanityfair.com/society/2012/02/ladies-who-lunched-201202 ↩