One basic modern need is to escape the feeling that desire has gone stale. Fashion therefore depends on managing the maintenance of desire, which must be satisfied, but never for too long.

Anne Hollander, Sex and Suits, 19941

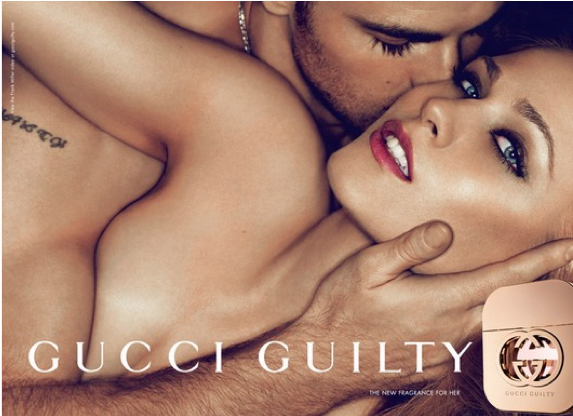

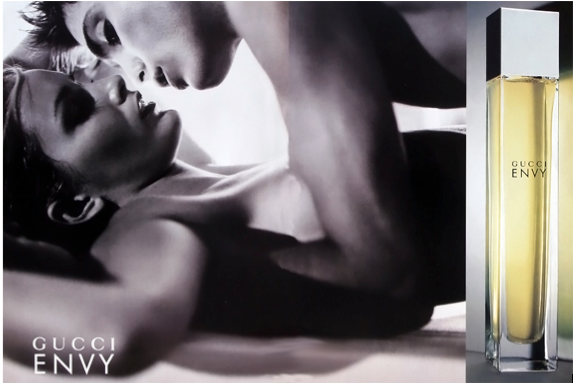

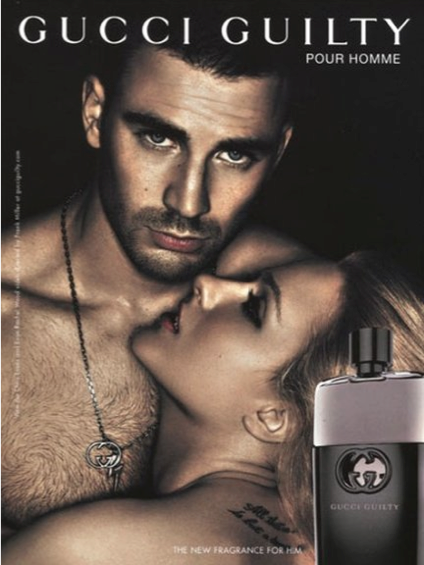

FASHION, SEX AND FRAGRANCE. All are, whether in a tactile, carnal or olfactorial sense, desires to be fulfilled but also generators of desire in themselves. A large motivating factor in dressing and scenting ourselves is in the hope of attracting a sexual partner; we dress to be undressed, and scent ourselves to invite someone to take a step closer. Both sight and scent work on a highly aphrodisiacal level and, more importantly, are marketed as such. When Napoleon wrote to his wife Josephine asking her not to bathe for two weeks prior to his arrival so that he could fully enjoy her natural scent, he highlighted the sexual potency of scent. The power of scent to connect with a carnal desire for sex is a concept that is crucial to fragrance advertising, which markets itself through gendered sexual stereotypes. The age-old adage of ‘sex sells’ is as important to fragrance marketing as it is to fashion. Cultural and social critic Susan Kaiser describes a ‘gendered system of looking’ in which ‘sex sells, and it is usually women’s bodies that are represented and “consumed”.’2 For example, Gucci’s fragrances Envy and Guilty are illustrated with images that adhere to the notion of the heteronormative male gaze. Although one might hope that Guilty’s his and hers advertisements would at least offer equal exploitation of the sexes, even in the female fragrance version, the models’ body language points to a passive woman, who is to one extent (physically) restrained by her lover, and to the other (in the Gucci Guilty Pour Homme advertisement), literally clinging to him. The world of Guilty is one where not only lust wins over love, but a white, thin, young, female body is passive object within it.

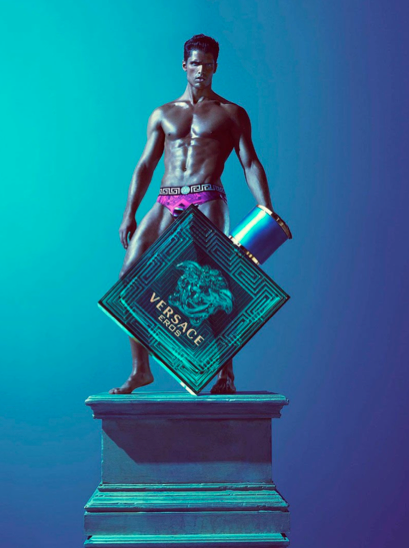

In fragrance, as in fashion, the male gaze is also directed at the male figure. In the Versace Eros campaign, model Brian Shimansky, with his highly-defined torso and chiseled facial bone structure, embodies the hyper-masculine Adonis. While the house of Versace may practically be built on sex, it also makes an abundance of references to Greek mythology, a theme that, in this context, conjures imagery laced with homosexual narratives in figures such as Homer and Sappho. The model’s tanned body, oil-slicked and clad in bright pink briefs, presents more a metrosexual, or even homosexual – as opposed to a heteronormative – archetype. Shimansky’s body may exude strength, but can one not also see him, perched atop a pedestal, as a passive object of desire?

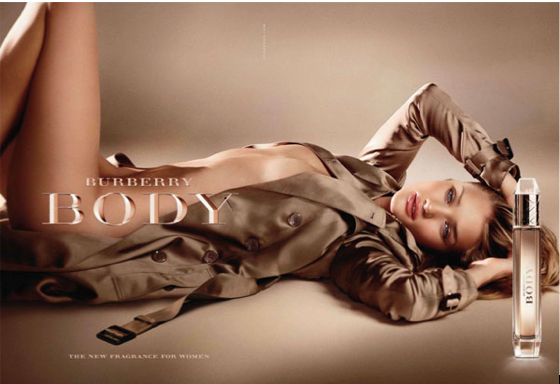

According to Kaiser, ’clothes like bodies or appearance styles in general, can be turned into symbols that are desired or fetishised’3, Burberry continues this notion by draping its trademark trench coat on an otherwise naked model for an advertisement for its fragrance, Body. Here the trench coat, a defining symbol of Burberry embedded in traditional British style, is transformed into a sensual, seductive garment. The advertisement rebrands the iconic trench highlighting the sexual potential for the garment, and for the Burberry brand. Since sexuality is an engendered concept, aesthetics in fragrance advertising are targeted to the relevant gender. As typographer and historian Charles Bigelow states, ‘Perfume is marketed as an agent of communication of social messages and, par excellence, of sexual messages – romance, aphrodisia, seduction – and it is not surprising, therefore to find that gender is strongly marked in perfume typography.’4 This is clear in the campaigns of Vera Wang’s Lovestruck or Dolce & Gabbana’s Dolce fragrance. Both employ a rounded, handwritten style font, which reinforces a softer, more feminine, aesthetic.

Aiming to capitalise on the primal desire that scents represent, fashion brands produce images that speak to our consumer desires in a way that only reinforces stereotypes surrounding gender and sexuality. While this sexualisation in fragrance seems inevitable, it still reinforces unrealistically and problematic ideals of beauty. Whether in matters of style, sex or scent, consume with care.

Carla Seipp is a freelance fashion, arts and fragrance journalist.

Hollander, Anne. 1994. Sex and Suits. New York: Knopf. p. 49. ↩

Kaiser, Susan. 2012. Fashion and Cultural Studies. London and New York: Bloomsbury. p. 128-129. ↩

Kaiser, Susan. 2012. Fashion and Cultural Studies. London and New York: Bloomsbury. p. 149. ↩

Bigelow, Charles. The Typography of Perfume Advertising In: Fragrance: The Psychology and Biology of Perfume. Edited by Charles S. Van Toller and George H. Dodd. London and New York: Elsevier Science Publishers Ltd. p. 255 ↩