WHEN AMINE BENDRIOUICH WAS interviewed by Vogue Italia in 2018, the second question posed (after ‘Who are you?’) was, ‘How do you relate to North Africa as a designer and creative mind?’1 Fashion designers outside the established fashion capitals are repeatedly considered according to (the references they make to) their cultural identity, while European designers will rarely be asked to explain or justify their references in regard to their cultural/national identity (just imagine asking Nicolas Ghesquière to explain his French references in his work for Louis Vuitton). Today a designer can easily be born in Morocco, grow up in France, study in Brazil and work in Korea. Does this make his or her work Moroccan, French, Brazilian or Korean? The so-called ‘globally recognised signifiers,’2 be it wax-print for African designers, bold colours for Latin American designers or minimalism for Asian ones, are not only a stubborn heritage of Eurocentric imperialist thinking, but also a persisting means to differentiate, diminish and exclude ‘Other’ fashions from the dominant Eurocentric fashion discourse.

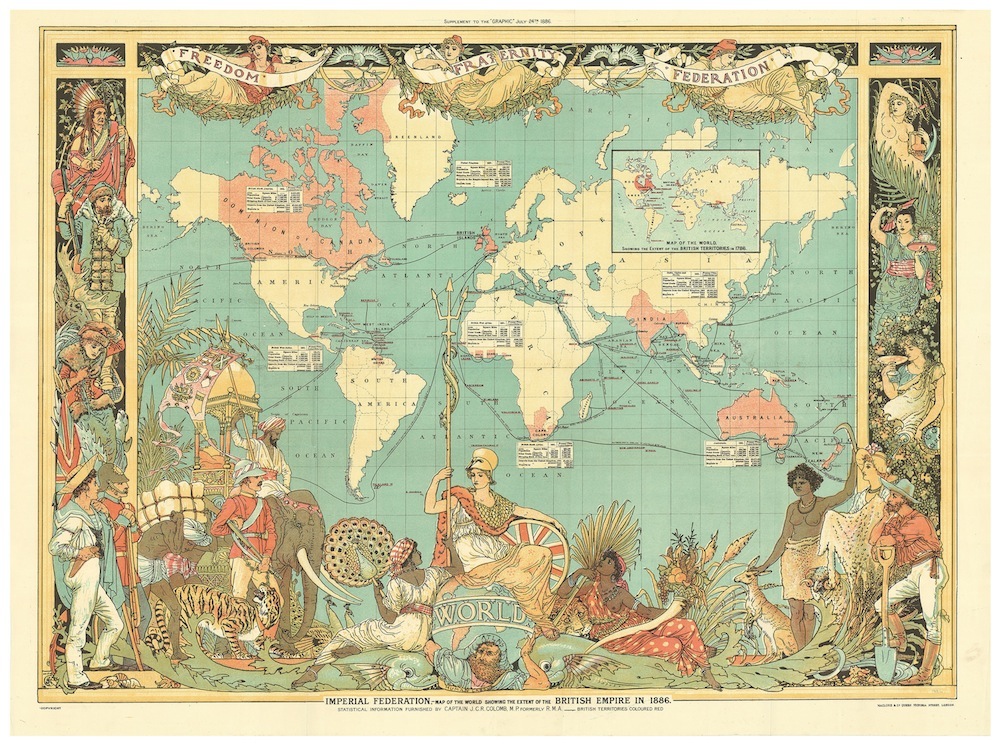

These stigmatised ideas of the ‘Other’ are remains of Western imperialist rationale when colonised societies and cultures were defined as traditional (e.g. unchanging), authentic (e.g. geographically isolated) and ancestral (e.g. historically disconnected) to emphasise their difference with European society and culture, believed to be ‘modern and cosmopolitan,’ as a means to justify oppressive and abusive colonial politics. In other words, if these people were ‘uncivilised,’ it was Europe’s ‘moral duty’ to ‘civilise’ them through colonialism. Historians, archaeologists, ethnographers and even artists were employed by colonial authorities to document local cultural heritage and, as was proper to the time, did so in orientalising and folklorising ways. They stripped these societies and cultures from their rich, dynamic and often globally interconnected (fashion) histories, turning them into ‘people without history’3 and therefore ‘un(der)developed.’ A common preoccupation of the colonial era was to create inventories of indigenous cultures to distil a diffuse and disordered reality into more rational categories, based on collective identities, organised in terms of gender, ethnicity, religion, region, tribe, etc.4 They especially focused on isolated rural areas to establish these inventories, because change and external influences were slower and less obvious, and therefore more compelling to their expectations of the traditional/authentic/ancient.

After independence, most formerly colonised regions united in nation-states for the first time and found themselves in need of a unifying national identity. Ironically, these colonial writings, representing a snapshot in time, provided nationalist movements with a ‘traditional/ancient/ancestral’ cultural heritage on which to construct unique and distinct national identities.5 This not only permitted them to clearly differentiate from the foreign oppressor, but also to justify new political power structures based on (constructed) historical grounds. By selecting specific garments, patterns and materials to symbolise national identity, while deliberately omitting others, the nationalists once again erased multifaceted regional diversities and historical dynamics in the name of national unity. Therefore, in the same way colonisers aimed to distil and organise a ‘diffuse and messy reality’ into streamlined categories, nationalists aimed to create unity to symbolise a unified nation, erasing complex histo-geographical multiplicities. Also, the same prejudices once introduced by colonisers to justify their modernity and superiority, were reproduced by nationalists to validate national identity and political structures as traditional and ancestral.

Meanwhile, referencing cultural identity through the use of (stereotypical) cultural heritage has become an important marketing tool for fashion designers outside the established fashion capitals. Amine Bendriouich’s answer, for example, to Vogue Italia was, ‘North Africa is the place that influenced me the most as it’s the environment in which I was born and raised. Being Berber, Tuareg and Arab exposed me to a rich cultural heritage that includes a lot of different tribes from the African continent. I think this heritage appears in my work quite spontaneously through the shapes, volumes, colours, details, and accessories that I blend with all my other influences, from street culture or whatever comes my way.’6 These designers have been turning to their cultural heritages to establish ‘different and unique’ design identities. They have been especially introducing textiles and decoration techniques that were previously used in ‘traditional’ objects like religious items and/or rural clothing of specific regions, because of their association with tradition or authenticity and therefore considered more exotic/different/unique. Although all designers (including European ones) consciously or unconsciously reference their cultural identity in their work, only designers outside the established fashion capitals are considered accordingly as a means to differentiate and exclude them from ‘mainstream’ fashion. For example, while Dolce & Gabbana might build their brand by referencing (a cliché of) Sicilian heritage/identity, they are still considered as ‘real fashion’ – a Moroccan, Indian or Kenyan designer referencing his or her (clichéd) cultural heritage are typically thought of in terms of ‘reimagining tradition’ (or some such nonsense), which in turn is, consciously or subconsciously, pitted against ‘real’ fashion.

Designers from former colonised countries are bound to use stereotypical references (as documented under colonial rule) in their work, because they have no knowledge of their indigenous fashion histories, which have all too often been erased or reduced to a static snapshot in time, and qualified as ‘traditional dress.’ The ‘natural’ historical continuity of their cultural capital was not only interrupted by colonialism, it was also robbed of its historical dynamics through colonial historical writings. Today, dominant Eurocentric fashion discourse upholds this narrative by arguing that designers outside the dominant fashion capitals are ‘modernising traditional dress,’ as if it was happening for the first time in centuries. We conveniently forget that, as part of indigenous fashion systems, these practices have been innovating and adjusting to new fashions throughout history by merchants, craftsmen and designers, a fact that has been and continues to be systematically erased and denied by our Eurocentric discourse.

A recent example of this practice is an article published by The New York Times Style Magazine entitled ‘The Designer Reimagining Traditional West African Fabrics for a New Generation.’7 It portraits Kenneth Ize, a Lagos-based designer, as the European fashion elite’s latest discovery (and nominated as a finalist for 2019’s LVMH Prize for emerging talent). In true colonial style, he is pictured as single-handedly saving through innovation ‘centuries-old techniques that are in danger of disappearing’ (due to mass-production introduced by the very same dominant Eurocentric fashion system). The textiles and weaving techniques that Ize uses (‘traditionally reserved for special occasions’ to add to the exotic myth), are pictured as having no dynamic history of their own, and the continuous development and innovation that they (and all clothes everywhere) are continuously undergoing is once again denied. Clichés of ‘undeveloped and poor Africa’ are even (unconsciously and most probably not deliberately) confirmed by the designer who explains that his collaborators live in ‘small and isolated villages that aren’t always easy to find.’ ‘There’s no real institutional framework to mobilise or support people who still practice this artisanship here,’ he explains, while ignoring the poor reputation and social status these artisans have been suffering from ever since colonial rule ensured that their craft shifted from ‘fashionable’ to ‘traditional’. Journalist Elizabeth Coop writes that ‘Ize’s collections feel both contemporary and rooted in the traditional garments he remembers his mother wearing during his childhood’ and ‘he is helping to sustain these crafts by creating innovative clothes for a younger generation,’ sentences which differ not at all from colonial discourse aimed to exoticise, differentiate, discriminate and exclude the Other. Although Kenneth Ize aims to ‘show a different, or at least a more nuanced, picture of African life and culture,’ he is unfortunately mainly confirming our clichéd and stigmatised ideas of the continent.

To ‘self-orientalise’ or ‘self-exoticise’ is a powerful marketing tool which works well both on a national and international level. Nationally it has enabled designers to compete with international fashion because it meets desires of localness that foreign brands cannot, while internationally it fulfils desires of the exotic or different associated with the designer’s country of origin. However, this practise also puts designers in a bind, since their marketability lies in their association with cultural difference, while this same cultural difference prevents their full membership in an ostensibly universal fashion community, composed of individual designers who (claim to) transcend the creative constraints of a single cultural tradition.8 The way anthropologist Claire Nicholas formulates it, these designers negotiate the reproduction of essentialising and Orientalising displays of tradition/authenticity, while claiming cosmopolitan inspiration drawn from other traditions, similarly simplified as Indian, African, Asian and European.9

The clichés on which these cultural identities are constructed, however, are in urgent need of deliverance from both ‘the white man’s gaze’ and cultural reductionism due to national identity politics. The way Kenyan creative director Sunny Dolat formulates it in his book Not African Enough, contemporary African fashion designers who step outside the narrow confines of what the world – and other Africans – considers to be ‘African,’ are frequently accused of ‘not being African enough.’10 The focus on heritage, he explains, often meaning a snapshot of the past as defined by the ‘white man’s gaze,’ has overshadowed the wider shifts into a globalised, more equal understanding of Africanness. Contemporary African fashion designers, he says, assume the power to describe and analyse their own worlds relative to their diverse points of view and it should not matter that a design is from Africa just because it is made from wax print. Just as copying any garment in wax print became the singular textile representation of the African continent, leading to a dearth of other forms of design, many designers outside the established fashion capitals have been limiting themselves to a selective set of garments, materials and decorations considered representative of their cultural identity (both by the West and fellow countrymen). As Sunny Dolat argues, there is a need to dismantle the super-concept ‘African’ as the assembly of words, images, sounds, ideas, weaknesses, histories and failings associated with an entire continent.11

Hence, decolonising fashion is about the obliteration of the Eurocentric cultural episteme, whereby European fashion remains ‘the norm’ while Other fashions continue to be considered ‘in relation to.’ The way Walter Mignolo and Rolando Vazquez, two influential thinkers in the discipline of decolonialism, formulate it, (Euro)modern aesthetics have played a key role in configuring a canon, a normativity that enabled the disdain and the rejection of other forms of aesthetic practices.12 Decolonial aesthesis, they say, is an option that delivers a radical critique to modern, postmodern, and altermodern aesthetics and, simultaneously, contributes to making visible decolonial subjectivities. They argue that decolonial aesthesis is a re-valuation of what has been made invisible or devalued by the modern-colonial order. A word like ‘fashion’ is not only not universal, but in its association with colonialism conceals a diversity of ideas and ways of relating to the world that does not belong to the genealogy of Western tradition. Aesthetics, they argue, as many other normative frameworks of modernity, has been used to disdain or ignore the multiplicity of creative expressions in other societies. For Europeans, the rest of the world never reached the state of producing art, literature or fashion; it is stuck producing ‘arts-crafts,’ ‘myths’ and ‘costume.’13

So, evaluating the work of designers outside the established fashion capitals according to (references made to) their cultural identity not only continues to fulfil ‘the centre’s’ need to distil a diffuse and disordered peripheral Other into more rational categories based on collective identities, but also to differentiate and therefore discriminate and exclude, while simultaneously protecting its own boundaries. By setting this fashion apart as ethnic, Moroccan or Asian, it not only diminishes it and discards it as ‘not real’ fashion, but also confirms French, Italian, American or British fashion as ‘real’ or the norm.’ Initial qualifications like primitive/folk/exotic dress may have evolved into traditional/ethnic/world fashion, but this does not make it less discriminating. As the anthropologist Sandra Niessen formulates it, binary oppositional thinking like dress versus fashion, traditional versus modern, Western versus non-Western, is not only a way to preserve the boundary between the West and the Rest and to protect Europe’s position of power, but also to ensure the maintenance of a conceptual Other on which to rely for purposes of self-definition.14 This being said, it is important to note that just as the West/modernity/fashion needs the Non-West/tradition/dress to define itself, the same holds true for the other way around. Therefore, as Sandra Niessen argues, on each side of fashion’s conventional divide we find people speaking the high and low dialects of the same global fashion language, whether they are protecting the exclusiveness of Western fashion or defending the purity of traditional attire.15 But where the so-called exotic Other was at first depicted by the dominant West as a passive victim of its static traditions, it now takes agency and uses these traditions to construct and formulate distinctive and unique (fashion) identities. In the process, however, there has been a shift from orientalising to self-orientalising, whereby the so-called ‘white man’s gaze’ through hegemonic Eurocentric discourse is appropriated and continues to dictate what Other fashions should be and look like.

So, returning to our initial question of whether a designer’s work should be classified as Moroccan, French, Brazilian or Korean, there is only true answer. It is completely irrelevant.

Angela Jansen is a fashion anthropologist based in Belgium.

https://www.vogue.it/en/vogue-talents/news/2018/05/23/african-fashion-morocco-amine-bendriouich-marrakech/?refresh_ce= ↩

William Mazzarella, Shovelling Smoke: Advertising and Globalization in Contemporary India, Durham: Duke University Press, 2003. ↩

Eric Wolf, Europe and the People Without History, Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1982. ↩

Claire Nicholas, ‘Of Texts and Textiles…: Colonial Ethnography and Contemporary Moroccan Material Heritage,’ The Journal of North African Studies, vol. 19(3), 2014, pp. 390–412, p. 398. ↩

Andre Adam, Casablanca Essai sur la transformation de la société marocaine au contact de l’occident, 2 tomes (Paris : CNRS), 1968. ↩

https://www.vogue.it/en/vogue-talents/news/2018/05/23/african-fashion-morocco-amine-bendriouich-marrakech/?refresh_ce= ↩

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/01/t-magazine/kenneth-ize.html?action=click&module=Well&pgtype=Homepage§ion=T%20Magazine ↩

Claire Nicholas, ‘Creative Differences, Creating Difference: Imagining the Producers of Moroccan Fashion and Textiles,’ in After Orientalism: Critical Perspectives on Western Agency and Eastern Re-appropriation, Pouillon and Vatin (eds.), Leiden: Brill, 2015, pp. 236-250: 237. ↩

Ibid. ↩

Sunny Dolat, ‘Not African Enough,’ Business of Fashion, retrieved on 29-01-2018 from https://www.businessoffashion.com/articles/intelligence/op-ed-not-african-enough?utm_source=Subscribers &utm_campaign=9380a8492a-hottest-bran ↩

Ibid. ↩

Walter Mignolo and Rolando Vazquez (2013), ‘Decolonial AestheSis: Colonial Wounds/Decolonial Healings,’ Social Text Online, retrieved on 21-11-2018 from (https://socialtextjournal.org/periscope_article/decolonial-aesthesis-colonial-woundsdecolonial-healings/ ↩

Ibid. ↩

Sandra Niessen (2003), ‘Afterword: Re-Orienting Fashion Theory,’ in Sandra Niessen, Ann Marie Leshhowich and Carla Jones (eds.), Re-Orienting Fashion: The Globalization of Asian Dress, London: Berg. ↩

Ibid. ↩