Kay Boyle was an American poet, novelist, journalist and translator. As a young writer she worked for several fashion journalists, an experience which informed this excerpted short story “Anschluss,” originally published in Harper’s in 1939. A contemporary of William Carlos William, Gertrude Stein and Hart Crane, Boyle was a victim of McCarthyism in the 1950s and lost her position as a foreign correspondent for the New Yorker. She went on to participate in many activist movements, including the strike at San Francisco State University in 1968 and that decade’s protests against the Vietnam war.

SHE HAD COME OUT in July to Brenau for two years now, and back twice at Christmas: Merrill, the fashion-editor’s assistant coming from Paris for her vacation in Austria, stepping off the train into this other world of mountains and seeing the dark forests’ shapes lying unaltered in the grass or snow. Fanni was at the station every time to meet her, the strong black silky braids pinned up high round her head and wearing her homemade dirndl and apron.

It might have been Fanni that brought her back: they reached out their arms to each other and kissed each other’s face; but even while the slow, low American voice was saying, ‘Fanni, here I am again. Here I am back, Fanni,’ the travel-weary and fashion-weary eyes were looking for something else besides the scenery and the voice was waiting to say it.

Fanni stood looking at her, the smile fixed on her mouth, seeing again not in desire or envy but with awe the mascara on the lashes, the hats that varied from summer to winter, from Descat to Schiaparelli, marveling at the undying scent of Chanel in the Paris clothes.

‘Is it possible, Fanni, I’m back?’ the voice went on saying, the naive youthfulness and blitheness masking for a little while the satiety and the concern, calling attention wildly for a moment to something fresher than the scars from thirty years of being gallant and bright. ‘Fanni, you’re looking so … ‘ [this or that or the other thing.] Or, ‘I simply love your dress or your shoes or your jacket – it’s quilted, isn’t it? You must tell me which shop it came from. I’ve got to have one to take back to Paris. They’d be crazy about it.’

If the hotel porter didn’t come at once Fanni, being the younger, stooped and without difficulty picked up one of the pigskin bags. They would argue about it, one of them wearing high heels and the other broad hand-stitched sales, because Merrill said it was much too heavy for her; and then when the porter came at last the American woman began laughing her soft, quick, youthful laughter. She couldn’t think of the German words to say any more – only ‘Guten Tag‘ and that was as far as she could remember. Out of the station the three of them went, the hotel porter carrying the bags and laughing, and the two young women holding arms and laughing, out into the unfailing miracle of the wintry starlit world or into the stormy blue summer evening’s light.

Outside in the square, Merrill knew all the horses and she had saved sugar for them from the dining car. Sugar for horses, said the eyes of the porters and eyes of all the drivers on the boxes of the open carriages or sleighs, and even Fanni’s dark, quiet eyes said it. It was a thing they never got used to seeing: just one more of the lavish, unthinking gestures foreigners made over and over, like ordering whisky in the face of poverty. At one season they would be carriage-horses when she came, drowsing there in the sun with their feed-bags on their noses; and the next time they would be wild eager creatures with their breath white on the air before them, shaking their harness bells and pawing at the thick-packed snow.

Only when the two women got to the Gasthaus and sat down at the long, clean, polished table in the public room did Merrill say the words that had been there every instant, what she had come across these countries alone to utter, had waited, mouth shut and eyes worn with despair over cocktail glasses, manicure tables, typewriter keys, programs of couture openings, shorthand notes, to ask month after month, ‘Fanni, how’s Toni? How is he making out?’

She looked away when she said it, taking her gloves off or her cigarettes out, or seeking for her lighter in her bag. Nothing was ever changed in the warm dim room except the season’s changes: one time the tall tiled stove hot to the hand and the next time cool, and hot red wine in the glasses instead of beer. Or else the changes in the waiters’ faces: this one in jail for political agitation and another one moved on to somewhere else because he had worked his three months out of the year there and could go home and collect his dole in leisure for the months ahead. And Merrill, drinking the beer or the wine and chewing at the big tough pretzels, would look at something else and say:

‘How’s Toni, Fanni? I must say he’s the most unsatisfactory letter-writer! What’s he doing now?’

Fanni would take a swallow from her glass and shake her head.

‘Doing?’ she’d say, wondering anew that this useless and uneasy thing must be asked. ‘Oh, nothing. You know the way it is here. There is nothing for anybody to do. He makes things out of wood of course a little, and he plays, you know. He plays the harmonica most of the time.’

That was the sign for them to burst out laughing again, screaming, shrieking, rocking with laughter together, as if Toni were the name for half-wit, for village nut, for the queer white-headed boy; or as if this were a family joke they’d never get over if they lived to be a hundred, a pain in the side, an ache in the face season after season instead of the two syllables describing glory, naming at last the animal and golden-flanked Apollo toward whom their love turned, sistered by his power. Here they sat, summer or winter, laughing fearfully at it: Toni, my brother, said Fanni’s slow, silent, loving tongue, and Merrill strangled in her nervous fingers Toni, Toni, my strange, wild, terrible love – the two women laughing and laughing as if the time would never come to wipe their eyes and speak coherently of him.

This year they had left it like this: whether there was the Anschluss or whether there wasn’t, they would meet in Brenau toward the middle of the summer just the same. You can’t change a people’s ways or their faces overnight, Merrill said for two months to herself in Paris. Her right hand was free of its good glove, and the silver-mounted pencil in her fingers flew at the paper while the mannequins in winter suits, fur wraps, ski ensembles came down the carpeted floor toward the double row of seated women, hesitated, turned lingeringly, and mounted the salon’s length again. ‘Really adorable fur buttons, leather-frogged,’ she jerked down, ‘like your very smartest Hussars.’

Her left fingers took the cigarette from her lips and snuffed it out in the metal engraved dish while her right hand blocked quickly down in the still girlish American script: ‘Upper sleeves built to assist any filly beyond her first carefree youth to shoulder the responsibility of looking sixteen and spirited this winter.’

Outside was the Paris heat, July’s, and Merrill thinking: once this farce of the openings is through I’ll set my lovely profile toward the heights. Everyone, mannequins, sister-journalists, sales ladies to be split into two categories if you caught them unawares: those who went upward out of choice and looked a mountain in the eye and those who took their clothes off at once and went to sleep on beaches. The Nordic and the Mediterranean blood, each manifestation of it going back to its source, like eels up out of the water with a flick of the tail and covering ground, field, thicket, swamp,wood, returning to their own latitude to breed.

‘Hats this winter,’ she wrote, ‘are likely to be taken by your little girl to put on her Dy-dee doll if you don’t watch out.’ All the seas in the world could dry up and the beaches tum to oyster shells and 1 wouldn’t care, she thought, noting that wimples were worth a word or two, as long as they left Austria and the mountains and the people exactly the way they were.

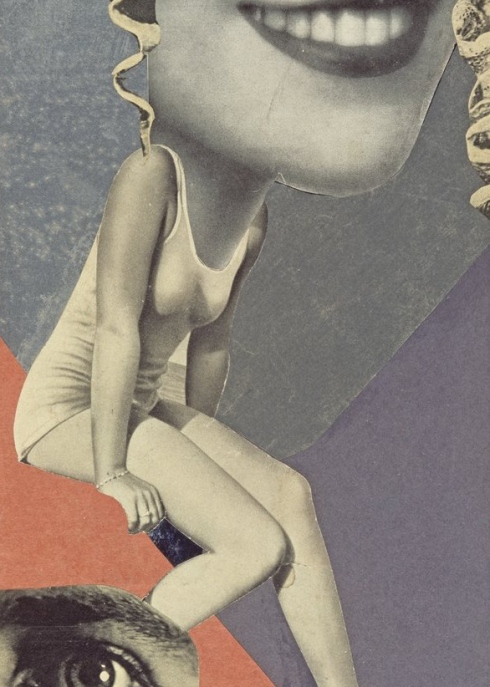

(Made for a Party), Hannah Höch, 1936

…

In January, just before she must get back to Paris for the openings, they arrested Toni again and put him into jail. But there was no shame or even wonder to it as there would have been in any other place on earth. It was merely another part of the spectacle to see him at the high barred window, his ski-jacket on because there was no heat inside those walls, and his harmonica playing fast and recklessly. Fanni and Merrill went down the back-street at night and tried throwing a comb up the height of the Rathaus to him, and it struck three times against the bars and fell again before he got it, and each time he missed it he giggled like a girl. That’s what I love, she thought wildly; that’s what I love – that dark faceless shadow leaping like a fool for a comb to do his hair with, laughing like a nut when perhaps they’ll hang him tomorrow, and she turned to Fanni with her voice shaking in her throat.

‘Political agitation,’ she said fiercely, as if she had not said the same thing a hundred times before. ‘But what kind of political agitation? Why can’t he have a lawyer and a room to himself if he’s a political prisoner?’

‘Mein Gott, it’s nothing!’ said Fanni. This softness, this female fury in the strange foreign woman was enough to take even the significance of truth away. She stood, a little shorter than Merrill, in the snow-covered back-street, both of them held and hidden in the shadow of the Rathaus wall. The street lamp was farther along, but even without its light Fanni could see or else remember the beauty of the other woman’s face, fragile, nervous, balked, with the little lip trembling and the eyes painted blue and starry as a child’s, and the child’s hood fastened underneath her chin. There was the actual sight or else the photograph of it fixed indelibly in Fanni’s dark, shrewd, merry eyes. ‘He’ll be out again in three or four days,’ she said, wanting to touch Merrill’s arm perhaps but not knowing how to make the move. ‘It’s happened so often. It happens to them all if they go round lighting the fires. It’s treason – is that the word you said it was? – yes, treason, a small treason, very little, to light the swastika fires on the hills at night.’

‘Peaches!’ Toni’s voice called down to them. ‘Merrill, can you got me peaches?’

‘Get, not got!’ Fanni called up the wall. ‘It’s a joke,’ she said to Merrill. ‘He thinks that is very funny. He saw those pictures with colors on them about peaches in the American magazines you have.’

‘Fanni, I can’t bear it,’ said Merrill in a low, fierce voice. ‘I can’t bear it. I’ll get him diamonds. I’ll buy his way out if they’ll let me.’

All the way back to the middle of town they could hear the harmonica playing, the little grief in it now nursed in the hollow of his hand and asking in warbling nostalgia for a homeland that had perhaps never been or for a hope without a recognizable or possible name to give it. Night after night he played until the evening he came out, and Fanni walked on ahead to let them kiss each other by the wall.

‘Merrill, I like the perfume again,’ he said against the hood’s fur.

‘Toni, Toni,’ she said, holding to him, and she felt the tears running down her face.

‘Toni, we can do something together. You don’t have to stay here. You could go to France with me – you could – ‘

‘I’ve never been into a city,’ he said.In a minute he might begin laughing out loud at the thought of himself wearing city clothes. ‘I have to stay here in my country. I’m too poor a one for you.’

‘I’m old enough to take care of you, much older than you,’ she whispered and he held her hard against him.

‘You are my doll,’ he said, saying it savagely and hotly against the hood’s white fur. ‘You smell good like a doll, and little small teeth like that. If I wanted to do it, I could break you as children do with a doll, pull your arms out and break all your little bones in your skin–’

He bit quickly at her cheek and chin and lip, soft, dry, nibbling bites at powder, scent, and rouge, and she looked up at him with the tears still on her face.

‘Toni, I’ve put red all over your mouth and my mascara’s running,’ she whispered.

‘I’ll keep your red like that,’ he said. ‘I’Il keep it like that on my face. I’ll never wash it away.’

Then in 1938 it happened; it happened in the spring. The German troops went over the border without a word and there was the Anschluss, and maybe he’ll be singing a different tune about it now that he’s got it, thought Merrill. Perhaps he’ll want to get out of the country by hook or by crook now he’s got what he’s been wasting behind bars for. They won’t be able to change his face or the shape of his hands or his mouth singing what words he did; not love ditties on top of a mountain, nor popular airs, nor things of classic pricelessness, but the pure loud clarion call of ‘Austria, Awake, Awake!’ Awake and in your right mind by this time, I should hope, thought Merrill, buying the ticket to go back; united and awake and in her senses she can’t cast the pearls of his teeth before swipe nor squander the fortune of his glance on one direction. His country nor no other can make a law abiding man out of what he is. He’ll go on rebelling, shouting the Nazis down as he shouted the Catholics and the Communists and Schuschnigg out of countenance, revolting now in the same cool, careless way against what he’s been wearing the flesh of his bones to get.

For the first time, stepping off the train at Brenau, she could not fling her arms out to Fanni or kiss her face, nor draw that first deep draught of other air in before she said, ‘Fanni, it’s like falling asleep again and finding the same dream still waiting for you.’ This time she must stand waiting on the platform alone, turning from the far sight of snow on the mountain tops to the shady, summery road leading off under the heavy boughs toward the first hotels where the swastikas on the flagpoles folded and unfolded languidly on the breeze. Fanni did not come running late down the pathway worn along the rails nor call her name out across the picket fence. The sun shone hot in the waning afternoon, thunder clouds were gathering on the rocky horns at the valley’s end, and the horses sneezed in their feed-bags on the square outside. In a moment the hotel porter came through the station door, took off his cap, and said, ‘Heil Hitler’ and shook her hand.

‘Griiss Gott,’ said Merrill brightly, and then she started laughing as usual because she couldn’t think of the German words to say. ‘Und Fräulein Fanni – und –Fräulein Fanni?‘ She said it over several times to him, but he only shook his head and stooped to pick her bags up. All he knew was that the hotel had raised his wages and that the place was full of Germans, full of them, just like the old days again before the frontier was closed, and they’d put a new uniform on him. He made her feel the cloth of the jacket. ‘Oh, gut!’ said Merrill, having forgotten the right word to say. ‘Perfectly lovely. Très gut, Hermann!’

At the Gasthaus the letter was waiting for her, and standing in the room where Fanni had always been she read it once quickly, and then reread it slowly. After she had folded it in the envelope again she took it out and stood reading it over. You will forgive me for not being at the station, Merrill, or words similar to this it said. Now I am district nurse and I cannot choose my own time. Today I must go on my bicycle to Kirchberg to arrange about the vacations for some expecting mothers and I shall then have to report what I have done at the office when I get back. So, please, may I come in this evening and see you? We are all very well organized now. Toni is Sports’ Organizer at the lake, so if you go swimming this afternoon you will see him. He is also Director of the Austrian Youth Local. Of course he is very proud. If you do not see him swimming, he too will come in and visit you with me tonight. So until we meet, my dearest friend.

Even the little bathing cabins, set out in rows on the south side of the lake, were topped by swastika banners, small ones fluttering in dozens against the wide somber mountain waters. This place, where before so few people had come, was now singularly alive: the refreshment tables crowded and bathers lying on the wooden platform that sloped to the edge, swimmers basking on the floats, bathers stretched reading their newspapers and smoking on the summer grass. Enormous, thick-thighed, freckled-shouldered, great-bellied people, not Austrians but invading cohorts come across the border with heads shaved close to baldness, speaking the same tongue and bearing vacation money to a bankrupt land. The air was filled with their voices as they called across the echoing waters, the hullabaloo of monstrous jokers gurgling at the surface, the shower and impact as the great bodies dropped from the diving boards and smote the tranquil currents with their mighty flesh.

Their bathing dress was dark and plain, the women wearing skirted ones with modest backs and necks, and Merrill changed into her pale-blue two-piece suit in the cabin and looked down at the strip of delicately tanned skin between the top and trunks and wondered. I never minded wearing this before, she thought. Why do they make me know I’ll look a queer fish among them: hair curled, mouth painted, thin as a rake, and half-naked? With something almost like shame she stepped out of the cabin door into the cool mountain air. The storm was gathering quickly in the valley and in a little while the sun would be gone.

Once she looked up she no longer saw the people: the heavy sloping shoulders, the shaved narrow pates, the folds of obscene hairy flesh at neck or chest, or cared for whatever insult or censure now stood in their eyes. Toni was on the springboard, ready to take the high dive, the heels lifted, the calves small as fists with muscle, the knees flat, the thighs golden and slightly swollen for the movement not made yet but just about to come. The throat, the lifted chin, the straight brown nose were set with cameo-clarity for an instant against the deepening sky, his arms thrown back and laying bare his breast as if for this once, just now, and this time forever, the shaft of love might pierce directly and the blood might flow at last.

‘Toni,’ she said in silence, ‘Toni, Toni,’ watching his hands part the surface and the body slide perfectly into the water’s place. Once he had risen, visible as light floating upward from the depths, and shaken the drops from his face and hair and thrust the locks back, she was at the edge and kneeled there, waiting. ‘Toni,’ she said out loud, and immediately he turned his head, wiping the water from his mouth and chin, and treading water. He took the five long strokes that brought him to her and reached his fingers to the edge of rotted timber and hung there, the hands tanned yellowish, the square nails clean, his upper lip drawn back upon his teeth, and then he lifted himself out, dripping, and stood on the wood.

‘Mein Gott, Merrill, you look like somebody from the theater,’ he said quickly. For a minute she might not have heard him, sitting there mindless, heedless, watching his wet bare feet stain the boards beneath them with water as if a shadow were spreading imperviously across the weather-rotted and time-rotted wood. She looked at the small, strong, perfectly molded ankle-bones with the skin drawn over them like tight, sheer silk, and suddenly, as if at that instant she heard the quickly uttered words or just at that instant understood, she jerked her eyes up to his face.

‘What time did you get in?’ he said. ‘Fanni showed me the letter you wrote. I thought you said this week some time–’

‘No, today,’ said Merrill. She sat squinting up at him, trying to shade her eyes and face although no sun was shining, feeling in panic her half-nakedness, the thinness almost skeleton-like among these people, the strip of body between breast and navel obscene, infecund. ‘It’s quite gay here, isn’t it?’ she said, making a gesture with her naked pale arm and hand. ‘Quite different, isn’t it?’

‘No, it is not gay,’ he said. He was smoothing his upper arms dry with the palms of his hands. ‘They are not like the English and American people who came here before. They know we are a country, not a playground. They respect us. They do not come to dress up for parts in a musical comedy the way the other people did.’

She sat there at his feet, squinting up at him, watching him turn to pick the bath towel off the springboard’s trellis and start rubbing his shoulders with it.

‘It is very serious here now,’ he said. ‘You see how they dress? Fanni will tell you how things have changed for us.’ And then he said quickly, ‘The nails of your toes, Merrill,’ squatting down on his thighs to come nearer to her and so say it the more violently and brutally. Merrill looked startled the length of the legs curved under her to the ten dull red medallions varnishing their extremities. ‘Wear that in Paris. Wash it off before you come here to us,’ he said. ‘Now we’re busy we haven’t time for people masquerading. We aren’t the tourists’ paradise any more. People can’t come and pay to see us dance and roll over on our backs like bears with rings through the nose–’

‘Toni, you got what you wanted, didn’t you?’ Merrill said in a low, quiet voice, sitting there without movement, even the nervous hands lying still. ‘You got what you were working for, didn’t you, Toni?’

‘Yes,’ he said, ‘yes,’ and then he said, leaning again, ‘Merrill, don’t go, but just put a bathrobe round you. Everyone here is looking at you like something out of the Tiergarten. Nobody’s used to suits like that or paint like that on the mouth–’

That was the next to last time she saw him. The last time was when she took the train the day after at the station, and he was there on the platform with half a dozen others, all young, all neatly uniformed in gray and green and smartly belted at the waist. They were there to meet the Innsbruck train which must have been bringing officials on it, and when he saw her on the other side of the glass his face altered and he took a step forward as if he were about to speak, as if it were not too late to say it. But the movement of the car passed like a veil between them and he brought his heels sharply together and lifted his right hand and she saw his lips open as he spoke, either ‘Heil Hitler’ or ‘Aufwiedersehen–‘ and that was all.

Kay Boyle was an American poet, novelist, journalist and translator. As a young writer she worked for several fashion journalists, an experience which informed this excerpted short story “Anschluss,” originally published in Harper’s in 1939. A contemporary of William Carlos William, Gertrude Stein and Hart Crane, Boyle was a victim of McCarthyism in the 1950s and lost her position as a foreign correspondent for the New Yorker. She went on to participate in many activist movements, including the strike at San Francisco State University in 1968 and that decade’s protests against the Vietnam war.