I miss going out dancing. Dressing up in something slinky that moves when I move, wearing impractical shoes… Nowadays I just stomp about in sensible footwear. I move differently, I think we all do. I pay attention to different parts of my body. I pay attention to the space around my body.

What follows is a flight of fancy through twentieth-century performance art, grounded in my day-to-day reality. An investigation into the kind of dancing we are doing now, and a consideration of how clothes might be employed to determine gestural formations and peripatetic navigation. In short, how gesture and clothes might move others away from us and in doing so may briefly unite us.

The other day I was part of an accidental group dance:

I was on my way to work. I stepped off the train carriage onto to the platform at Cambridge Heath station, turned right, walked a little forward, and began to descend the narrow stairwell. Well, mid-descent I caught up with the man in front of me and I wanted to overtake. I was however unconvinced that there was suitable space to feel confident that I could make such a move. The margin of empty space was ambiguous and on top of that I never know how much room I myself take up. I was whirring through these calculations, when, with the slightest of gestures, the man in front made my decision for me. He extended his arms outward with his hands strained so that the palms were horizontal, parallel to the ground. I understood his sign and maintained my distance behind him. The people behind me however were beginning to get frustrated with this designated pace and I was soon overtaken, only for my overtaker to find that they could not overtake the man whose arms had sprung out once more, this time with stronger intent (tauter wrists, flatter hands). The unsuccessful overtaker was forced to remain behind and I, obligingly, allowed them to slot in front of me. This strange wriggling and reshuffling was silently negotiated in as little time as it will have taken you to read this. Although fleeting and relatively commonplace, each move made within our troupe of five was deliberate and considered, each gesture read and understood. Looking back, I think of this pedestrian event as an improvised dance of socially acceptable distance.

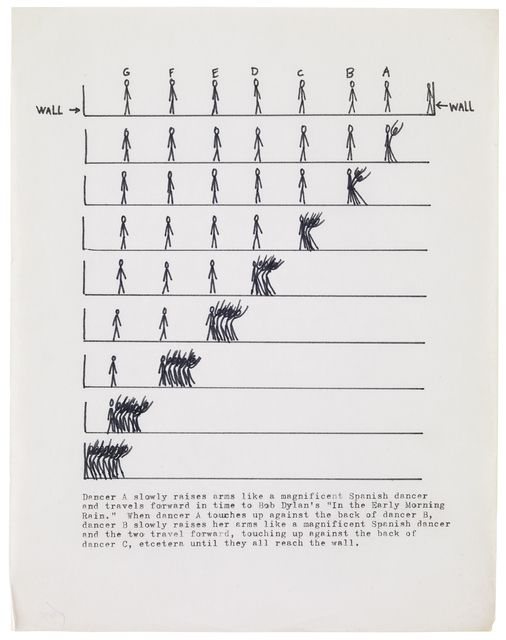

In 1973, Trisha Brown choreographed a work called ‘Spanish Dance.’ In it five dancers stand equidistant from one another, all facing the left wall. Dancer a, who is furthest from the shared focal point, begins the piece by raising their arms, then, wiggling their hips, they shuffle forward toward the next dancer along the line (b). Once a bumps into b, b then raises their arms and the pair move forward as one unit until they bump into c, c then raises their arms, and the three snake toward the next dancer. This routine continues until the group of five, all squished against each other, finally squish into the wall and can go no further.

The wiggling episode performed by the quintet in the stairwell reminded me of ‘Spanish Dance.’ That is, if ‘Spanish Dance’ didn’t reach its conclusion, if it ended with four dancers pressed together whilst the fifth dancer maintains significant space around them, and, of course, if those four dancers weren’t actually pressed together but stretched apart like an open accordion.

Trisha Brown along with her contemporaries at the Judson Dance Theater sourced their choreographic material from everyday occurrences. Seemingly unremarkable itinerant routines – hopping on and off the curb, walking, running and hailing a cab – were all plucked from the street and incorporated into the repertoire of postmodern dance. Stripped of flourish and theatricality to evidence action in plain sight; dance became task.

The matter-of-factness of pedestrian acts provided Brown with a means to study the operational logic of gestures without metaphor or distraction. She broke habitual movements down into their constituent parts – a bend, a stretch, a rotation – and arranged them within a spatial and temporal system. A delineated choreographic structure enabled her to demonstrate how minute motions accumulate to form a corporeal rhetoric which is then read and interpreted by those beyond the performer. Brown was not only concerned with the gestures themselves but the durational cause and effect that such gestures have on other bodies and the space around those bodies.

In ‘Spanish Dance,’ we can all anticipate the comic finale from the very first ‘bump,’ but Brown makes us watch and wait and in doing so builds suspense with a kind of Chaplin-esque chain of circumstance. It’s a wonderfully pared-back exercise in slapstick, demonstrating how the progression and proximity of gestures make an individual activity into group activity, but what I just can’t get out of my head is that moment just before the quintet are unified. The four with their bonded shaking hips, and that lone figure standing in front, untouched, as if a forcefield surrounds them. Currently we are all required to be that individual, with that space around us, and the accompanying idiom is that our lives have ‘been put on pause.’ The dance has been paused.

Well, actually, nothing has been paused. Despite the state rhetoric of ‘locking down’ our physical movements haven’t been suspended, they have adapted: adapted to demonstrate our participation in a new, collective, movement practice called social distancing.

He extended his arms outward with his hands strained so that the palms were horizontal, parallel to the ground. I understood his sign and maintained my distance behind him.

The gestures of the man on the underground form part of this, not necessarily new but nevertheless topical, rhetoric of distance. I’ve seen people jogging with their arms extended like wings and others lurch off the pavement onto the road, risking ensuing traffic to evade human contact. There seems to be either the tactic of retreat – ducking, dodging and swerving – or the unwavering confidence that the other will and must move. These gestures all ask of the other ‘please don’t touch me,’ or the more assertive ‘don’t you dare touch me.’

However, sometimes a gesture alone is too subtle – it requires your fellow company be conscientious and accommodating. Sometimes we need clothing and props to make that gesture unmissable. Through the mobilisation and alteration of articles of clothing, the ‘keep your distance’ gesture can extend beyond your body proper to demarcate your preferred spatial boundaries. I’ve sourced some examples from female performance artists to offer up strategies for choreographing distance; fail-safe methods that have already had a test-run on the street.

Between 1970 and 1973, conceptual artist Adrian Piper took to the streets of New York for a series entitled ‘Catalysis.’ For these works Piper performed a variety of pedestrian tasks – commuting, visiting the library, attending an art gallery and browsing shops – but she did so with various modifications to her appearance. For example, in Catalysis I she boarded a train at rush hour wearing clothing saturated in a mixture of vinegar, milk and cod liver oil. For Catalysis III she slathered her clothing with white paint, attached a wet paint placard to her chest and went shopping at Macy’s. Had the man in front of me been soaked in paint and stench, well then, the very thought of slipping in front of him mightn’t have even crossed my mind – hell, I would have stayed far back.

In conversation with art historian Lucy Lippard, Piper explained that these operational – and confrontational – acts in public spaces not only let ‘art lurk in the midst of things’ but that they provoke ‘an active and undetermined response’ in herself and from others (rather than the standardised set of responses triggered by gallery settings).1 Wet paint and pungent aromas transgress social codes and elicit a hyper-awareness of the dangerous permeability of passing bodies, forcing passers-by to reconfigure their proximity to such. The sticky, smelly clothing attracts and repels, latching onto whoever is near, encouraging people to physically steer clear, simultaneously summoning the gaze and deterring the body. By drawing attention to subliminal personal boundaries Piper commented, ‘I want to register my awareness of someone else’s existence, of someone approaching me and intruding into my sense of self, but I don’t want to present myself artificially in any way. I want to try to incorporate them into my own consciousness.’2

Piper’s clothing alterations act as catalytic agents, introducing novel physiological and psychological negotiations within quotidian conduct. In these performances the passing pedestrian is necessarily implicated as an essential component in the reaction. It’s a causal chain of circumstance again, wherein, as Piper states, ‘the art-making process and end product has the immediacy of being in the same time and space continuum as the viewer.’ ‘Catalysis’ ultimately has no independent existence outside of its function as a medium of change, demonstrating that any one movement doesn’t exist in a vacuum but is always relational. Even in separation, there is continuity, in avoidance, interdependence.

If you’re not prepared to soak your clothes in cod liver oil then perhaps a huge pair of green gloves would be more to your taste.

In the early Seventies Sylvia Palacios Whitman was a dancer in Trisha Brown’s company. In 1974 she started making her own performance work, often employing untrained participants to move in and around certain objects and costumes. At the Sonnabend Gallery in 1977 she showcased ‘Passing Through,’ a piece in which she wore various props, most notably a very, very large pair of green gloves. A photograph taken by Babette Mangolte of Whitman performing ‘Green Hands’ has been widely circulated and is relatively well known although Whitman herself remains relatively unknown.

‘Green Hands’ was first shown in a gallery, but it was also taken out onto the street. Two years ago, Whitman donned the gloves again and made her way across the Brooklyn Bridge. Speaking of this iteration of the performance she said, ‘you’ll see that the performance incorporates people on the street. In New York, people are all going about their business, and then some of them see me with the green hands and don’t know what to think.’3 You can find the video footage of this performance online and it’s quite wonderful. People jog past, others stop and stare, some are amused, some bemused.

Piper and Whitman’s exaggerated alterations to the body index relationships beyond the body. Piper explains, ‘the immediacy of the artist’s presence as artwork/catalysis confronts the viewer with a broader, more powerful, and more ambiguous situation than discrete forms or objects.’4 The ambiguous situation – provoked and exposed by Piper and Whitman’s conspicuous gestures – is the hidden logic (or illogic) of street etiquette, a choreography in which we all partake.

‘Catalysis’ and ‘Green Hands’ confront the very nature of confrontation; how the body can be activated, extended and interpreted to intrude on ‘space.’ The body is in space, the body is space, space is never neutral. Right now, space holds the righteous function of safety, but space cannot withhold that safety without the cooperation and coordination of bodies. Sociologist of space Henri Lefebvre once wrote, ‘I see the humble events of everyday life as having two sides: a little, individual, chance event – and at the same time an infinitely complex social event.’5 If we are to effectively maintain ‘social distance’ then it is a decidedly social task.

What I experienced on the London underground, recognised in ‘Spanish Dance,’ and see in these works by Piper and Whitman is the shared understanding that a single gesture has a cumulative effect. From a subtle flick of the wrist to an enlarged green hand, these individual, improvised yet intentional movements compel others to change their footwork, gait or path accordingly. So, when feeling despondent from the profound lack of crowd-generated energy (a Londoner’s bread and butter), I propose we turn to our clothes and our gestures, and in studying their signals and the reactions we receive, we might find that despite distance, dance lurks in the midst of things.

Isabelle Bucklow is a graduate in anthropology – visual culture from University College London, and works as a researcher and writer at Atelier Éditions Publishing.

Adrian Piper Talking to Myself: The Ongoing Autobiography of an Art Object, Bari: Marilena Bonomo, 1975, p.54, p.47 ↩

Lucy Lippard and Adrian Piper, ‘Catalysis: An Interview with Adrian Piper’, The Drama Review: TDR, 16:1, 1972, p.76 ↩

Wera Hippesroither and Sylvia Palacios Whitman, ‘The Artwork Speaks by Itself’, PW-Magazine, 2019, https://www.pw-magazine.com/2019/sylvia-palacios-whitman-the-artwork-speaks-by-itself/> ↩

Adrian Piper Talking to Myself: The Ongoing Autobiography of an Art Object, Bari: Marilena Bonomo, 1975, pp.42-43 ↩

Henri Lefebvre, Critique of Everyday Life: Volume 1, London: Verso, 1991, p.57 ↩