ACCORDING TO THE PHILOSOPHERS Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, in art as in philosophy authors create conceptual personae as productive tools to express ideas and suggest new modes of thought.1 Friedrich Nietzsche signed himself ‘the Antichrist’ or ‘Dionysus crucified’ while Joseph Beuys crafted his ‘shaman’ persona for his Actions from the 1960’s forward to combine his spiritual inclinations with unorthodox materials and a ritualistic brand of performance art. The same is true for artistic collectives such as Invisible Committee and Bernadette Corporation, which can be seen as examples of ‘collective conceptual persona[e]’ in that they are groups who perform a fictive person by ‘opting for opacity.’2 In fashion, both designers and brands can become ‘social and/or artistic masks.’3 Designers or brands often employ a conceptual persona as productive tool to describe their creative approach or express their philosophy. The recently renamed Maison Margiela has successfully chosen anonymity as core value and PR strategy since its establishment, often using the mask both literally and metaphorically.

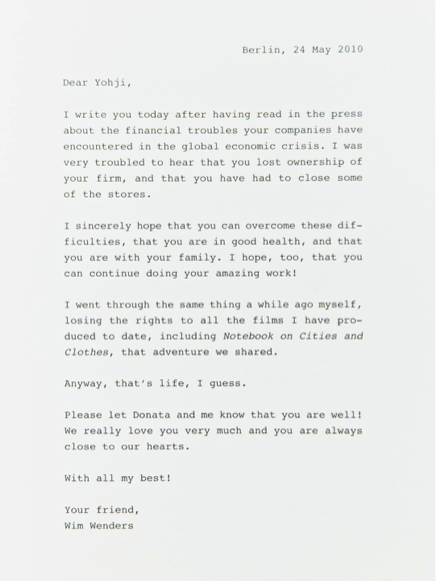

Yohji Yamamoto’s autobiography, My Dear Bomb (2010), similarly creates a complex conceptual persona of a designer, that of the ‘insider/outsider.’ A composite autobiography; the text of My Dear Bomb is a collection of multiple voices, writing styles and visuals. The designer’s own poetic writing dominates the text of the book, but is punctuated with other ephemera: recorded conversations with writer Ai Matsuda, lyrics to songs by Yamamoto, as well as short contributions and letters from friends and critics. Visuals such as photographs and sketches confer to the autobiography elements typical of journals and sketchbooks. Throughout the book, and in the obscurity of its non-linear narrative, Yamamoto positions himself as an outsider despite the fact that he is celebrated as a ‘designer’s designer’4 by the fashion industry at large. The book is an extension of Yamamoto’s practice but ultimately reinforces the core values and aesthetic of the Yamamoto brand in the creation of this paradoxical persona.

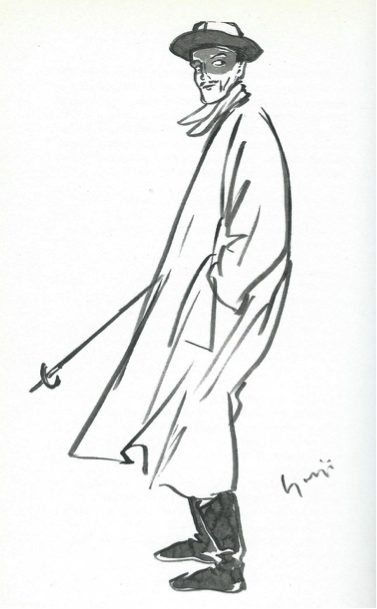

Throughout My Dear Bomb, Yamamoto maintains a resistance to the fashion industry. Reflecting on his 1981 debut in Paris, which received criticism from mainstream press and established his cult-like following, in the book the designer explains this ambivalent position with a metaphor: ‘I was turning my back to stick out my tongue at the world, so when they praised me for it, I immediately felt uneasy.’ This oppositional stance to the industry, and accepted notions of fashion, is reiterated with the use of militaristic terms. His relationship to fashion is a ‘fight,’ a ‘struggle,’ a ‘battle’ motivated by ‘anger’ and ‘rage’ – a careful selection of words that underlines Yamamoto’s awareness in crafting his persona and philosophy. Fashion itself becomes a war-like endeavour: ‘Simply put, the work of a fashion designer is a battle with tailoring.’ These principles can be seen in Yamamoto’s women’s and menswear, which regularly seek to challenge the association between Western femininity, display and sexuality and traditional notions of masculinity and power. This outsider stance, further developed in My Dear Bomb, extends beyond fashion and embraces broader socio-cultural systems of control, including bourgeois values and gender roles, an ingredient essential to the Yamamoto brand.

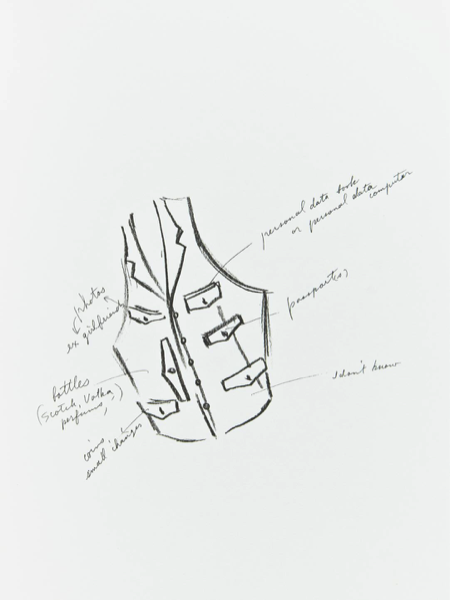

In My Dear Bomb Yamamoto’s conceptual persona is reinforced in the poetic style in which the book is written. The text resembles that of poetry or music, rather than a traditional narrative of autobiography. Throughout the book the author regularly likens his work to other components of the arts: according to Yamamoto, in fashion, as in music, the hand of the designer must be practiced like a ‘finely tuned piano’ to create a garment that will have a life of its own and ‘begin to sing.’ Even functionality is bestowed a lyrical quality in Yamamoto’s descriptions, where pockets are ‘for storing treasures,’ the ‘life or death of a garment depends on finding the point of rapture’ for a button and ‘the pleasures of attaching sleeves are like those of building tunnels.’ Yamamoto indirectly becomes himself a poet, musician and architect, creating secondary conceptual personae that reinforce his status as a fashion outsider, while simultaneously projecting an artistic aura onto his designs and, by association, his brand. By proclaiming himself an outsider, then, he engages in a branding strategy that paradoxically reveals his position as an insider.

The evocative language of these moments of reflection on craftsmanship through metaphor, imagine new possibilities for fashion as discourse and practice. By enriching its vocabulary, Yamamoto indirectly offers alternative approaches of engaging with the subject of fashion based on the richness of materiality and the bodily, sensorial experience it can trigger. In particular, references to touch and hearing throughout My Dear Bomb offer a unique insight into the potential of the ‘erotics of design’5 to enrich everyday life and the human experience. Like Thomas Carlyle’s tailor in Sartor Resartus, though lacking the irony of the original, the designer’s words elevate fashion to the status of an autonomous artistic realm that may even offer reflections on the human condition:

‘Just as man lives and grows old, so too does fabric live and age. When fabric is left to age for a year or two, it naturally contracts, and at this point it can reveal its charm. The threads have a life of their own, they pass through the seasons and mature. It is only through this process that the true appeal of the fabric is revealed. […] The intense jealousy I occasionally feel towards used clothing comes from this fact. It was in just such a moment that I thought, “I would like to design time itself.”’

Simultaneous to his symbolic struggle with mainstream fashion, My Dear Bomb reveals a reverence to the craft of fashion that encourages us to read Yamamoto as an ‘insider’ to the fashion community. He admits a sense of companionship with the likes of couturiers Jean-Paul Gaultier and Azzedine Alaïa in their quest for the perfect construction. When discussing the issue of the neckline, for instance, he declares himself jealous of Sonia Rykiel’s perfectly calculated round neck rather than Rei Kawakubo’s neckline, a ‘hole for the neck’ that she masterfully opens with bold, punk-like attitude. Yamamoto’s views on garment construction confirm his position as colleague to these influential designers of the past three decades, and embeddedness within these ranks in the fashion industry.

The book My Dear Bomb as an object itself fulfils Yamamoto’s trademark sensibility and ability to engage successfully with branding. The design of the book, by Paul Boudens, well-known for collaborating with members of the Belgian and Japanese avant-garde, reinforces the idea that, more than an autobiography, the book is an artistic manifesto. Yamamoto’s trademark black extends across the cover and on the edges of the pages. The paper of the book, coarse and thick, has a tactile quality that further reinforces an emphasis on the format, alongside content, of the book. My Dear Bomb in this sense is a collectible and a rare commodity in itself.

Anecdotal and often obscure, Yamamoto’s My Dear Bomb is lacking as traditional autobiography. However, it can be read as a highly refined and crafted manifesto in which Yamamoto as a person, his persona and his brand are inseparable. But if, as Deleuze and Guattari write, ‘the destiny of the philosopher is to become his conceptual persona or personae,’ My Dear Bomb allows Yamamoto to become, from time to time, a rebellious outsider, a critical insider, a master tailor, a warrior, a nostalgic poet, a sensitive musician and, ultimately, a designer whose success lies in the impossibility of pinning him down.

Alessandro Esculapio is a writer and PhD student at the University of Brighton, UK.

G. Deleuze & F. Guattari, What Is Philosophy?, London & New York, Verso, 1994. ↩

S. Lütticken, “Personafication: Performing the Persona in Art and Activism”, New Left Review, 96, Nov-Dec 2015. ↩

Ibid. ↩

L. Salazar, Yohji Yamamoto, London, V&A Publishing, 2011. ↩

A. Aldrich, “Body and Soul: The Ethics of Designing For Embodied Perception,” in D. McDonagh (ed.), Design and Emotion, Boca Raton, FL, CRC Press, 2003. ↩