MY HUSBAND AND I discover his shop on Nashville’s Broadway by chance. Not far from The Ryman Auditorium and down the road from a long string of honkytonks popular with bachelorettes celebrating their last single days, we are both drawn in by the gaudy designs and the multitude of rhinestones on display. He greets us smartly dressed in boots, well-cut trousers, a natty neckerchief and a black T-shirt with his own logo emblazoned in gold. His white hair is slicked back. He is eighty-three years old.

I was born in a little town in Mexico. I was the fifth of twelve: six boys and six girls. My parents had a hacienda. My dad was a salesman and so commercially smart he could’ve sold condoms to the Pope. He’d sell anything you can think of. He did a lot of travelling, a lot of dealing. I remember one time he told me he had a little business going that was doing very good. I saw him picking some junk up off the floor and I said, ‘Dad, what are you doing?’ He said, ‘This is money.’ I told him I’d make him a hobo outfit. (Laughs.) He was selling junk: broken televisions, broken shovels. Everything was broken. But there was always a hundred and fifty people buying, and a line of people waiting to pay. I saw it was successful but I don’t know how he did it. People love junk I guess.

My oldest brother showed me how to sew; he was playing with tailoring. I was seven and he was five years older. I was a different child. I got my doctorate degree in psychology when I was nineteen, so I was five, six years ahead of everybody else in school. Guys at school hated me, but I never competed with them. I was number one in class, all the time. I don’t know what to tell you. I came to this country and I was asked to become a citizen.

I sat down there at the sewing machine, and helped my brother to sew. I learned how to cut pants in two hours. When I was twelve I made seventy-seven prom dresses for the girls in my town. I thought they needed something different instead of going to the mercantile store to buy a dress. Actually, a lot of people get married in the same little poo-poo dresses – I’d never make one of those in my life. No one ever told me what to do. There’s people out there, you tell them what to do and they’ll do it. Their whip is their bank account. Money never meant anything to me: I had money.

Back then I looked weird: I’d have one cream sleeve and one royal blue sleeve – each side of my shirt was a different colour. The back was sometimes one solid colour, sometimes two. My trousers were also different. Everybody in my era had black trousers, tan trousers and white trousers. I had none of that! I love a lot of black, but colours is my number one. I looked like a dragon walking into a chicken coup. My girls were always very elegant dressed. I was in my own world. When I was in college people would come over to do homework and talk and learn how to cook. And they said, ‘Why, the way you are Manuel, why?’ I’m the architect of my own destiny.

I was making a lot of money – at the age of eight and a half I was making more than the banker. After making the seventy-seven dresses I went into the shoeshine business. I made shoeshine boxes and orange uniforms for my friends so they would stand apart from the other shoeshine boys. I made so much money. My story about clothing is just that I love to make clothing. I like to make every piece different to the next. My clients tell me, ‘I really love this jacket, make me one like it.’ I say, ‘In my place you never get what you see – it’s always different.’ And that’s what they love.

I moved to California in the early Fifties. It was a struggle at first. In the early Fifties, mass production was just starting and I did everything. I made sleeves, I made zippers – I knew every stitch. I learned how to do embroidery in California. A friend of mine was a model and she said let’s go to the Pasadena Rose Parade on the first of January – it was more famous than the Macy’s parade in New York in those days. At the time I was doing a lot of fittings for Mr Sy Devore who was the tailor to the stars in Hollywood. He gave me fifty-five dollars for a fitting. You know how long a fitting would take? Five minutes! Mr Devore guaranteed me three fittings a day; that’s why I went to work for him. I did fittings for Frank Sinatra, Johnny Weissmuller, Gregory Peck, Sammy Davis Jr, Bob Hope…

So I just fell in love with embroidery; I thought, ‘Gee, this is an English trade. Kings and Queens rest with embroidery.’ I found out the woman making the embroidery for the parade was Viola Grae, so I went to work with her. I learned; I listened to the master. But she did resent that I learned so quick. That was my problem all the time.

I always looked like a million dollars. I always looked good, and I was in a way very handsome. Who scores the ball? Manuel. Who’s the best soccer player? Manuel. The girls would say, ‘We know your teammates don’t want to admit it but you’re the alpha man.’ I was definitely overpowering. I learned English when I was six years old.

I met this chick one day, she was coming into a cleaner’s and I opened the door for her. I liked her – she looked very much like Elizabeth Taylor. It was Nudie Cohn’s daughter. She was working in the back of her father’s shop. Anyway I married that chick, my first wife ever. I had waited long enough. I worked with Nudie for many years: I was the head tailor, then the head designer and later his partner at Nudie’s Rodeo Tailors in North Hollywood. After my wife and I got divorced, I opened my own shop down the road from Nudie’s, and a lot of his clients became my clients. I’ve been married four times so far. To be an artist is… we’re hermits in a way, we’re like queen bees. I don’t have the time to be with a family. It’s just hard.

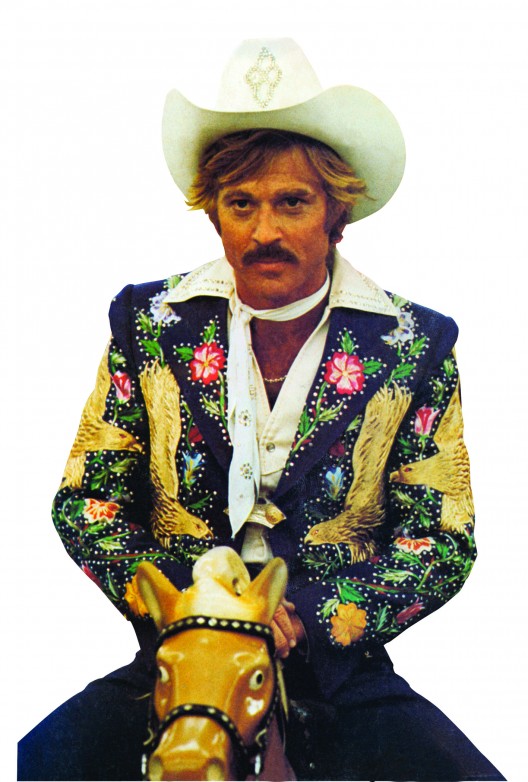

Eventually, they started calling me ‘Rhinestone Rembrandt’ and all this bull. Vogue magazine called me that. I’m so grateful for California: I really got into the movie industry. I worked with Edith Head. I made the jeans James Dean wore in Giant. I made a shirt for Salvador Dalí, and I got to meet Pablo Picasso. But after a while L.A. became… They were stealing transistor radios from cars; we were afraid to shake hands with friends lest they take your rings off. It got a little too tight for me. In 1988 I came to Nashville. By then I had in my arms a two and a half year-old girl – my third and last child. I bought my home and my joint in Nashville on the same day. I’ve stayed here, though my wife is no longer my wife, she’s gone. Then I had another wife – she’s gone too. Now I have another beautiful wife, Maria.

I’ve dressed kings, queens, beggars, prostitutes, lawyers, bankers. I dressed Gram Parsons, Dolly Parton, John Wayne, Sylvester Stallone, The Rolling Stones, The Jackson Five and all four Hank Williams. I made Elvis’ gold lamé suit, and people say that I put Johnny Cash in black, but I’ve never in my life felt the need to be important or rich. I hate money, because of what it does to people. When Barbara Walters asked Johnny Cash about the black suits I made him he said, ‘I wore black before, but nobody put me in a better black than Manuel.’ He called me one day and said, ‘This is Johnny Cash.’ I said, ‘I know who it is, you just have to breathe in the goddamned receiver!’ So he told me, ‘Brother, I want you to make me clothes for fifty-two shows. For the first time in my life I can afford to buy them.’ I made maybe five hundred different pieces for him, all black. When he got the clothes he asked me, ‘How come they’re all black?’ And I said, ‘Well there was a big sale on black fabric!’ (Laughs.)

I like to wear black too, and gold. The colours of oil and money. Money is the most pursued thing in life, but you don’t need to chase it. If you just keep producing, a lot of good is going to come your way. I was born under the sign of diamonds, I’m a Taurus, which also means I’m full of folly. I don’t care that much for the zodiac though: I am my own zodiac. Now what is your reading of me?

Interview conducted together with David Myron.

David Myron is a Paris-based craftsman and carpenter, as well as a regular Vestoj Salon collaborator.

Anja Aronowsky Cronberg is Vestoj’s Editor-in-Chief and Founder.