When Demna sent Crocs down Balenciaga’s runway in 2017, this literal platforming of the aesthetically offensive shoe apparently elicited an audible gasp from the audience.1 I also couldn’t help rubbernecking. Something about this sartorial collision in class and taste crashing Paris Fashion Week felt unexpectedly familiar. Nostalgic even. As much as these shoes were a logical response to a culture hell-bent on hustling viral content, engineered outrage and fake news, my mind recalled a much older kind of fakeness: the luxury fashion counterfeit. In particular, I wondered how luxury fashion houses had ended up producing goods that looked like the knock-off knick-knacks that filled the Chinese shopping malls of my youth.

Fashion magazines occasionally remind their readers to spare a thought for anonymous Asians in developing nations making and selling counterfeit luxury goods, yet they rarely report on how these individuals might themselves consume them. Certainly, little consideration is given to the way Asian consumers in the diaspora think about luxury. And yet, it is precisely this demographic, the consumer who is economically or culturally excluded from purchasing luxury goods while having direct access to their counterfeit counterparts, that has helped transform the industry into what it is today: a flattened spectacle where domains like class, identity and even politics have all collapsed into this thing we call fashion.

When I was growing up in the 1990s in Canada, counterfeit goods occupied a very different status than today. They existed in two parallel worlds. In the world of white, mainstream fashion commerce and journalism, counterfeit goods were objects of impersonation that were inherently discrediting. The rise of luxury handbags and their clever copies in the 1990s was such a cultural moment that a fake Fendi earned itself a cameo on a Sex and the City episode in which the main character is publicly humiliated for owning it.2

But in the marginalised world of Chinese immigrants, counterfeit goods were entirely normalised. In the malls of Toronto’s Chinatown and Chinese-dominant suburban neighbourhoods, commerce functioned according to a completely different logic. Bargaining was the norm (if not a competitive sport), retail stores were designed to cram in as much inventory as possible, and popular luxury designs were endlessly replicated in a fugue-like multiplicity. Here, the luxury retail experience was irrelevant and fakes spanned the gamut from caricatures to near-perfect clones.

Back then, on the spectrum of illegality, I placed buying and selling fake purses adjacent to speeding on the highway or smoking weed. Technically illegal, yes; in practice, so common as to be unremarkable. This shadow industry was so ubiquitous in my life, that I didn’t think twice about the fact that my friend’s parents owned a knock-off purse stand in one of Toronto’s Chinatown malls. In fact, my friend was not even aware of the original luxury products that these goods were mimicking. Neither she nor I recognised the triangular metal pieces glued onto her nylon purses as Prada, nor the horse bits as Hermès.

As outsider subjects, we had taken these signifiers out of their original modes of circulation. As aliens who did not speak the language, we had amputated the signifiers from their origin stories. After all, your relationship to luxury changes when your desire for upward social mobility is not focused on consuming signifiers of affluence so much as the need to achieve material security like good housing and employment in unfamiliar environments.

This is not to say immigrants, including those in the working class, cannot think of luxury goods as a means of projecting an image of success and affluence. But the relationship to luxury can be far from passive or servile. Like Hong Kongers making playful, absurdist choices for their children’s English names – names like Alphonse, Bambi and Cornelius come to mind – the diaspora rejects an earnest participation in a culture they are excluded from.3 It is at once buying into the power dynamic of a racist world order that’s been imposed upon you while demonstrating how much you don’t take it seriously at all. In this way and more, the people I knew detached luxury goods from their marketing and then homogenised them with a plethora of other ‘fancy white people things.’

I have so many memories of family members appraising both knock-off and designer clothes with only a vague appreciation for ‘fancy white people things’ and showing no actual interest in what these brands were supposed to signify. I can still recall bringing my Japanese friends visiting Toronto to shop at Abercrombie & Fitch and Victoria’s Secret; for them, all-American quarterback boys and next-door collegiate girls were indistinguishable from private-jet-setters donning Louis Vuitton or Chanel. I had assumed Japan’s greater economic integration with international markets would have made my friends more sensitive to the cultural and class differences signified by these global brands. Still, to them, all white people looked the same: well-fed and free of genuine worries.

***

I also observed globalisation changing these brands themselves. Many of the august fashion houses that were replicated in my friend’s Chinatown purse stall were eventually acquired and made over by the profit-squeezing machinations of multinational luxury conglomerates like LVMH and OTB Group. As fashion entered the aughts and luxury corporations began pivoting toward the bottom line,4 increasingly, their material goods came to reflect the homogeneity of ‘fancy white people things.’

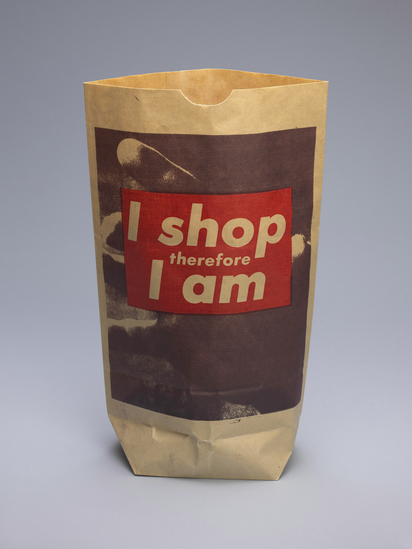

The meaning of luxury has collapsed not only to outsiders but from within as well. In order to tap into aspirational desires for designer items, executives pushed sales and diffusion lines in the aughts, flooding the market with discounts and monograms in the 2000s.5 In their ubiquity, designer logos began to circulate according to the same logic and volume as logos for gasoline, fast food, media channels and couriers, all mingling together in a kind of miscegenation for signifiers that all but invited the rise in pirated, bastardised goods. Meanwhile, the growth of outlet retailers and second-hand markets meant that designer logos were distributed en masse into spaces so far flung from flagship metropoles that today, there is nothing remarkable about spotting DKNY and Armani Exchange on the backs of migrant labourers, asylum seekers and the unhoused.

On the other end of our social strata, the rising glut of gabillionaires and the offshoring of luxury production – first towards formerly Communist European states and then the People’s Republic of China – have diffused the fashion industry beyond the Occident. Mainland China is not only a key luxury apparel manufacturer but also its driving force, engendering a new class of consumers with a yen for the fancier things in life.

This shift in sartorial meaning and fortunes has been fascinating to observe because luxury houses continue to cash in on the cultural cache of white supremacy. Fashion’s old guard still stubbornly upholds the image of a certain kind of producer for a certain type of customer, even as global market forces have destabilised the ground that gave rise to this image. It is both horrifying and satisfying. Horrifying to see these venerated luxury houses, hollowed-out relics of an aristocratic world order, cutting corners and abandoning the material underpinnings of their luxurious operations. Satisfying to see the same brands now trying to appease shareholders and executives who are courting mainland Chinese consumers with no allegiance to Eurocentrism and its values.

Of particular note are recent collections of printed leather goods and t-shirts from Givenchy and Gucci featuring Disney characters slapped over their logos.6 On the one hand, they are purchased by consumers with a playful irreverence for luxury items and produced in factories with no investment in the mythos of a house brand. On the other hand, one wonders at the offense felt by those tasked with upholding and projecting an image of old-world elitism for these houses. How does it feel to have signature handbags associated with signs of mass American consumerism for children? Does it rankle to represent a house that boasts a self-serious heritage of serving Europe’s upper crust when it is now producing goods pandering so blatantly to the Chinese nouveau riche, they resemble the purses that my friend’s mother would have sold at $20 a pop?

***

If anything, there is now something effortlessly authentic about knock-offs, whereas ironic marked-up collaborations feel overly engineered, cynical, and easily lost in today’s never-ending stream of online clout chasing. When I see Gucci’s Disney t-shirts, I can almost smell the sweat of marketing executives, chartered accountants and IP lawyers gathered in a boardroom.

Yet even this way of reading the fake feels like it is eroding. Global markets and increased migration are introducing an influx of shoppers who have no reason to employ Western notions of selfhood, authenticity and realism but instead bring their own ways to parse out what is tasteful and tacky, and the differences between acts of creation and counterfeiting.7 These newer consumers may not be particularly invested in any distinctions between a $2,000 Gucci Mickey purse, a $200 Coach version and an endless array of disposable $20 mimics just a convenient mouse click away.

And it’s not just the diaspora anymore. As inflation and cost of living crises continue to make life more difficult to afford for middle-class shoppers of any ethnic background, what is vulgar is not the fake, but the desire to distinguish the real from the fake.8 Today, someone who buys into the belief that luxury corporations are in the business of selling quality goods worth their ever-increasing price tags is the real dupe.9

It took decades to unfold in the mainstream market, but the collapse of signifiers that were all around me as a child: the commodifying force that flattened out all the ‘fancy white people things’ in the Chinese malls of my youth has finally been replicated at the height of high fashion. The cultural collapse delivered by capitalist logic imposed on so many descendants of the colonised has now come full circle to infect the upper echelons of colonial affluence.

I didn’t know it then, but fake purses were the forerunners of a culture where forgeries can be just as real as fact and the blue ticks can turn out to be fraudulent. Fake it till you make it, as the saying goes. What they never told us is that faking it seems to have been the goal all along.

Kawai Shen is a writer based in Toronto.

E. Harwood, ‘Crocs Get Yet Another High-Fashion Upgrade,’ Vanity Fair, 2nd October 2017, https://www.vanityfair.com/style/2017/10/paris-fashion-week-balenciaga-crocs, accessed 14th September 2023. ↩

S. Santiago, ‘I Started Rewatching ‘Sex and the City’ and Now I Have to Have a Fendi Baguette’, Racked, 21st February 2017, https://www.racked.com/2017/2/21/14594524/sex-and-the-city-fendi-baguette, accessed 14th September 2023. ↩

J. Man, ‘Hong Kong Loves Weird English Names’, Atlantic, 1st October 2012, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2012/10/hong-kong-loves-weird-english-names/263103/, accessed 14th September. ↩

D. Thomas, Deluxe: How Luxury Lost its Lustre, Penguin Press, 2007. ↩

A. Boutayba, ‘Logomania, the 2000s and Celebrity Culture’, Coulture, 16th August 2020, https://coulture.org/logomania-the-2000s-and-celebrity-culture/, accessed 14th September 2023. ↩

D. DiPede, ‘13 Of The Best Disney Collaborations In recent Years’, Style Democracy, 17th May 2021, https://www.styledemocracy.com/best-disney-collaborations-in-recent-years/, accessed 14th September 2023. ↩

L. Pang. ‘China Who Makes and Fakes: A Semiotics of the Counterfeit’, Theory, Culture & Society 25. 6, 2008. ↩

CT Jones, ‘How ‘Dupe’ Culture Took Over Online Fashion’, RollingStone, 15 September 2022, https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-features/dupe-culture-fast-fashion-tiktok-1234591964/, accessed 14th September 2023. ↩

C. Chen, ‘Why Luxury’s Counterfeit Problem Is Getting Worse’, Business of Fashion, 18th October 2022, https://www.businessoffashion.com/articles/luxury/fashion-counterfeit-problem-authentication-technology/, accessed 14th September 2023. ↩