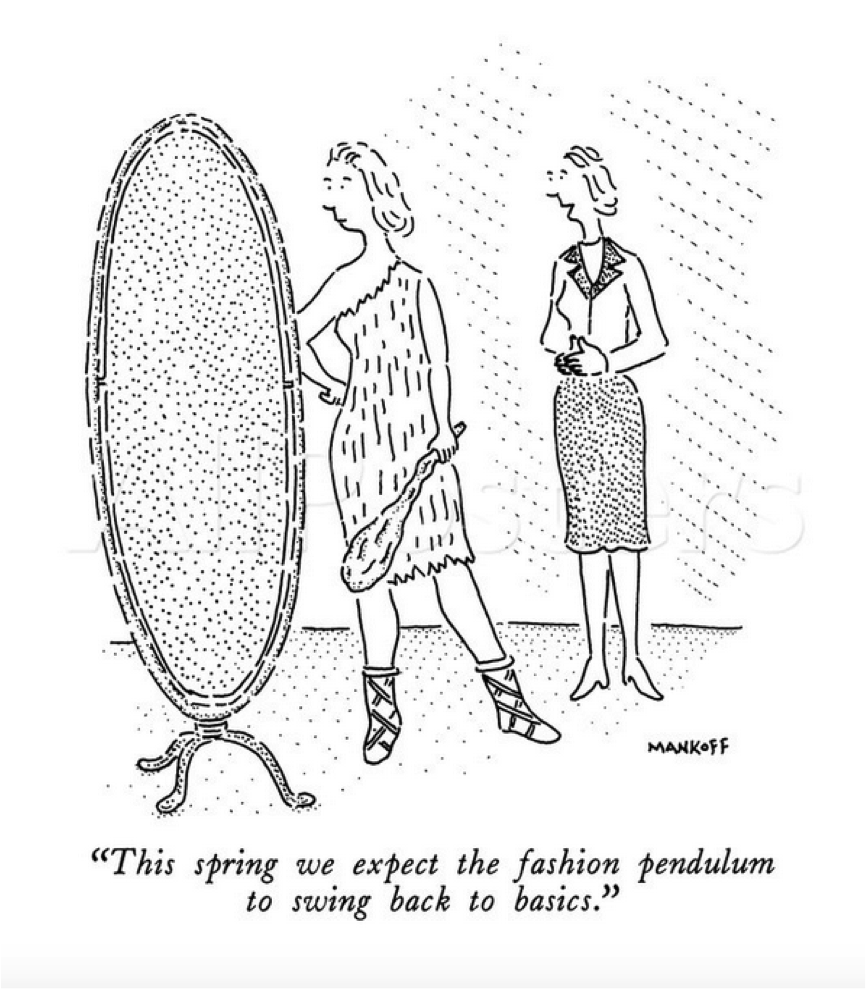

THE FASHION CYCLE, OR trend cycle, helps us trace a garment’s journey from ‘in’ to ‘out’ of fashion. It’s a idea most would be familiar with, even those who don’t maintain a particular interest in fashion, since it presents a framework for looking at the economics of the fashion system as a whole, encompassing high to low.

The concept was introduced in the late-nineteenth century by sociologist Thorstein Veblen when he began to analyse the emerging consumer behaviours of the middle class in his text, The Theory of the Leisure Class from 1899. Nowadays it’s a popular, albeit generalist, concept often bandied about, but in basic principle it offers a systematic explanation to the commercial ebb and flow of the clothes that we wear.

For fashion, the Trend Cycle is often represented as a bell-curve following the journey from fashionable to unfashionable. The ‘trickle-down’ effect is an explanation for this transition, which, as consumer culture scholar Angela Partington explains, ‘describes changes in taste as innovations made by the dominant class, given that modern social codes allow the immediately subordinate group to emulate the tastes and preferences of the one above. According to this model, the high status groups are forced to adopt new styles in order to maintain their superiority/difference, as these tastes filter down the social scale. This happens periodically so a cyclical process is created, generating the otherwise mysterious mutations we know as fashion.’1

Looking at the production of clothes as part of the Fashion Cycle has the effect of simplifying it all, distilling it into a formula that overlooks many of the subtleties of how we produce, buy and wear clothes.

***

Further Reading:

Every generation laughs at the old fashions, but follows religiously the new. We are amused at beholding the costume of Henry VIII, or Queen Elizabeth, as much as if it was that of the King and Queen of the Cannibal Islands. All costume off a man is pitiful or grotesque. It is only the serious eye peering from and the sincere life passed within it which restrain laughter and consecrate the costume of any people. Let Harlequin be taken with a fit of the colic and his trappings will have to serve that mood too. When the soldier is hit by a cannonball, rags are as becoming as purple.

The childish and savage taste of men and women for new patterns keeps how many shaking and squinting through kaleidoscopes that they may discover the particular figure which this generation requires today. The manufacturers have learned that this taste is merely whimsical. Of two patterns which differ only by a few threads more or less of a particular colour, the one will be sold readily, the other lie on the shelf, though it frequently happens that after the lapse of a season the latter becomes the most fashionable. Comparatively, tattooing is not the hideous custom which it is called. It is not barbarous merely because the printing is skin-deep and unalterable.

I cannot believe that our factory system is the best mode by which men may get clothing. The condition of the operatives is becoming every day more like that of the English; and it cannot be wondered at, since, as far as I have heard or observed, the principal object is, not that mankind may be well and honestly clad, but, unquestionably, that corporations may be enriched. In the long run men hit only what they aim at. Therefore, though they should fail immediately, they had better aim at something high.

Henry David Thoreau, Walden, 1854

Indecent – 10 years before its time

Shameless – 5 years before its time

Outré (Daring) – 1 year before its time

Smart – ‘Current Fashion’

Dowdy – 1 year after its time

Hideous – 10 years after its time

Ridiculous – 20 years after its time

Amusing – 30 years after its time

Quaint – 50 years after its time

Charming – 70 years after its time

Romantic – 100 years after its time

Beautiful – 150 years after its timeJames Laver ‘Laver’s Law’, from Taste and Fashion, 1945.

Fashion is the imitation of a given example and satisfies the demand for social adaption; it leads the individual upon the road which all travel, it furnishes a general condition, which resolves the conduct of every individual into a mere example. At the same time it satisfies in no less degree the need of differentiation, the tendency towards dissimilarity, the desire for change and contrast, on the one hand by a constant change of contents, which gives to the fashion of today an individual stamp as opposed to that of yesterday and to-morrow, on the other hand because fashions differ for different classes—the fashions of the upper stratum of society are never identical with those of the lower; in fact, they are abandoned by the former as soon as the latter prepares to appropriate them.

Georg Simmel’s essay, ‘Fashion’, published in the International Quarterley, 1904. (http://www.modetheorie.de/fileadmin/Texte/s/Simmel-Fashion_1904.pdf)

J Ash and E Wilson, Chic Thrills: A Fashion Reader, University of California Press, 1992 ↩