The summer I finished college I worked in a vintage shop in Dublin. I arrived every Saturday at 9am, dressed in all black and ready to set up. When the other girls were hungover the owner would remark on their hair or say ‘you’re a little slow today,’ but because I was always hungover she never mentioned it.

The owner had specified we only wear dark colours; presumably to enhance the aesthetic effect of the clothes for sale. We, the shop-girls, were visually pleasing but unthreatening scenery, foregrounding the garments as the dramatic actors of the space.

I had two pairs of cheap black jeans and three long-sleeved black shirts which I rotated for these shifts, where I would stand by the entry-way, in front of the many multi-coloured silk scarves. My job was to make sure no one stole the scarves and to convince people to buy the clothes. I wore shoes with rubber platform soles, which, if it was raining and I stepped quickly diagonally, led me to lose my balance and twist my ankle. In these nondescript work outfits I felt uniform, unidentifiable, and thus unassailable.

When I was not in the shop, I spent much of my time in borrowed clothes. The owner of the vintage shop would let the girls who worked for her borrow from her collection and I would sometimes walk home with a dress or a shirt for the week. I spent the rest of my time in items taken from my girlfriend’s closet, whose apartment I haunted, as my room was too small for us to fit comfortably. Her closet was full of clothes that I enjoyed wearing but would not have thought to buy for myself. Up until that point, I had only purchased from the women’s section. I had an aversion to basics. I liked clothes that were bright and textured and girlish. Her clothes were simple and masculine. Black T-shirts, button-down shirts. Wearing them I felt as though I was transforming into a new kind of person, one whose femininity was more relaxed and sure of itself.

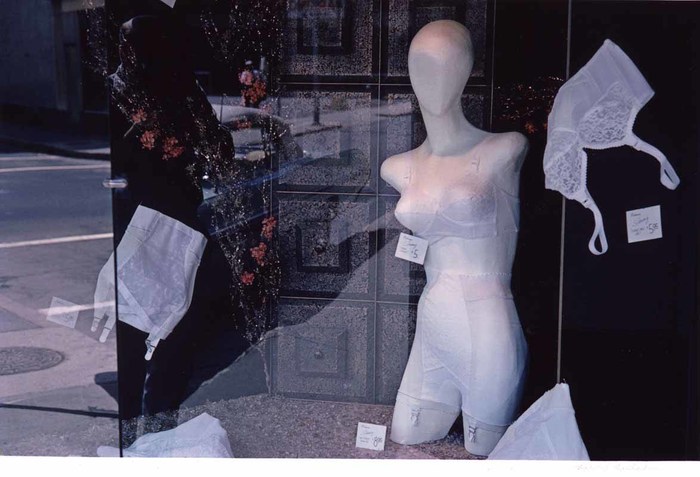

The shop moved clockwise through decades. It had to be set up anew every Saturday, bringing the rails of clothes down from the back room unsteadily down a ramp and through the small parking lot. The hat boxes and wooden coat hooks were stored during the week in the changing rooms; we draped plastic over them to protect them from dust and bird droppings. I moved the headless mannequin, dressed in a dark blue silk dress, to hide water damage on the wall. The shop was arranged carefully to hide any wear and, once set up, the CD player on and playing jazz, it was an entrancing, feminine realm. There was an abundance of luxurious fabrics and strikingly embroidered kimonos, glittering flapper vests, pretty silk dresses, and fur stoles were hung from the tops of the walls, above the clothes in lines on hangers. Before I worked there, I had been afraid to touch anything. The shop had reminded me of my desire, as a child, to sit next to a glamorous woman doing her makeup.

This taking-down and putting-back-up was a consequence of the building’s regular use. The man who owned the building parked his car there during the week. When we took down the shop after closing, walking past his parking spots, waiters on their smoke breaks could often be seen from over the wall separating our building from theirs. We would hear bits of their conversation as we pushed the rails of clothes back up into the back room.

The owner complained of the smell. ‘It’s that damn vegetarian restaurant,’ she’d say. Sometimes people brought us clothes to sell. Whenever a car stalled on the lane in front of the shop it was someone offering a deceased relatives’ furs. They popped out of their silver or black cars, the engine still running, and carried their bags to us. Usually we turned away the furs with compliments; they were not in good enough condition. I remember one heavy coat; it was a strange fur, from a male animal, and when I put it on I felt sunken. The owner looked at me wearing it for a long moment. ‘For a woman of another decade,’ she said. We did not take it. I was glad, because that would have meant dragging the heavy thing to the back, to hang with the other winter furs in darkness until they came back in season.

Girls in summer dresses came with small bags of clothes, sometimes looking to sell items they had bought from us a few summers ago. They always wore expressions that conveyed that they were running a day of many errands. I admired this in them and enjoyed hearing them tell us what they had done in the clothing they no longer wanted. One young woman, tanned and in a pink dress, told us she had worn the dress which she was now returning to a wedding. She took it out of her bag, a sheer turquoise floaty thing.

‘Ah, I remember you buying this,’ the owner said. She smoothed it onto the counter. ‘Lovely, but a little tight around the shoulders.’ I imagined her dancing at the wedding, adjusting the dress straps, realising she could not open her arms all of the way.

On a hot day, a little white fan running at the front counter, me sweating in my black clothes, two older lesbians came into the shop. They stood close to one another, in easy intimacy, as they looked at the scarves and the menswear section. They both had close-cropped grey hair, wore dark wash denim, and walked with a gentle butchness. I watched as one half of the couple tried on a bow tie, looking in the mirror as her partner watched her too. I was a little afraid for them; that someone would say something rude. I also desperately wanted them to look at me with a look of recognition. I had no way of knowing if they did. They only smiled politely as they left.

Some notable purchases: a mink wedding stole bought by a poker player for his new wife, early Gaultier designs taken home by an American mother and daughter with similar brightly coloured geometric glasses, a Burberry coat snatched by a painter with small bows tied into her hair, a chocolate brown Stetson hat bought by a man who came in wearing a vintage baseball cap which was stolen off of his person and I had to run into the street to retrieve.

Some notable borrowings: The first time I wore a suit – a real suit, not a ladies blazer that cinches the waist and trouser-pockets so shallow they can’t fit your whole hands – it was my girlfriend’s. I liked the way the silk lining felt on my skin and the boxy shape it drew of my body. Everyone drank too much, I got stuck in a crowd-crush, and ended the night crying – but the suit stuck with me. I wanted to dress like that again. From the vintage shop: A checkered Pendleton skirt I wore to a party where my shirt unraveled at the hem and dancing felt urgent; we had just broken up for the first time. A long 1960s flower patterned dress I wore on my balcony with my housemate talking about our futurelessness; we could not imagine futures for ourselves. A silk tie with a brown heart on it which I wore to a goodbye party for two friends moving to Australia, speaking to people I hadn’t seen since graduating, everyone had moved away. A drop-waist deep red velvet party dress which was so tight it made me sit up straight in the hot room I wore it in, sipping white wine and trying to pay attention to the author explaining the meanings of his short stories; we had just broken up for the last time.

Once, in early summer, after work I went to a house party where I did not know anyone very well. I drank too quickly, out of anxiety, and threw up for hours on my girlfriend’s balcony. She held my hair back as I said stupid things like how nice it was we had known each other for years, if not well the whole time.

In the morning I got a text that I was expected at my housemate’s mother’s funeral. There was a miscommunication, I hadn’t been told. My clothes from the previous day had vomit and sweat on them. In the dark, I took what I thought were black clothes from her closet and shuffled into her too-big shoes. There was no air conditioning on the hour long bus ride and I threw up into the paper bag my sandwich had come in. The bag leaked and I had to ask for directions to the funeral home. In the light, I saw that the trousers I had borrowed were a dark purple.

The rest of the summer eased under us like this – cold white wine over lunch, sweet fruit which burst into sourness, oysters promised but never ordered, flaky sea salt on breakfast, a new lipstick, a shirt-sleeve torn and returned stitched up, friends’ disapproval, words clipped from the day’s paper, walking to the sea on overcast days, wandering until I was tired. All events passed while wearing other people’s clothes. If the mood shifted at all, it shifted slowly.

At the end of the season, I found a black pinstripe silk Balmain Paris jacket in a thrift store. It fit perfectly around my shoulders. I wore the jacket over my black outfit to the vintage shop on a cold day. ‘This,’ the owner said, looking at me and holding my elbow, ‘is how you should dress.’

Ava Chapman is a writer and poet from Los Angeles living in Dublin. Her work has appeared in The Dublin Review, Trinity News and Trinity Journal of Histories. She was the 2022-2023 editor of Icarus, Ireland’s oldest literary journal, and currently serves as co-editor of Lesbian Art Circle, a publication and event series.