TODAY, HELMUT LANG WORKS as an artist. His minimalist and deconstructivist work is no longer presented on runways, but represented by galleries dealing in contemporary art. The narratives of his work emphasise the death of his fashion identity and point to his role as a new kind of creator. After resigning as creative director of his fashion house in 2005, Lang turned away from his former profession to focus solely on fine art. This decision came with creative freedom, unencumbered by the functional and economic restrictions of the moving body and wearability. From 2009 to 2010, Lang donated a large volume of his fashion archive to museums worldwide and – in that same year – a large fire in his New York studio destroyed most of the remaining archive. The destructive fire triggered a contrary reaction in Lang: why not just destroy his archive entirely? This idea generated the art installation ‘Make It Hard’, an exhibition presented in 2011 at The Fireplace Project in New York and recently installed at the Sperone Westwater Gallery, also in New York. The project that embeds Lang’s fashion archive into the art industry, forcing us to question the role of art to fashion, and – more pertinently for Lang – of fashion to the art world.

Whilst working in fashion, Lang spoke about his practise as being ‘against’ the commercial industry, as a part of a counter-movement that moved fashion towards a new kind of sobriety and away from 1980s glamour and excess. His aesthetic was very much born from the context of his time, and was a reflection of significant social changes in the beginning of the Nineties. Lang explained the conception of his runway shows as ‘séances de travail’ or ‘working sessions’: they were pitched as art events, performing the mood of the moment in which his designs were not just displayed as commodities for sale but rather as clothing that was actually worn by creative individuals. Besides becoming aligned with deconstructivism, Lang’s aesthetic was frequently described as minimalist. And indeed, his use of luxury materials, especially by the end of the Nineties, linked him closely to other minimalist designers like Jil Sander and Miuccia Prada, whose work shared the key features: simplicity and functionality. Yet, in Lang’s designs materiality was the starting point. His experiments with ‘outsider-materials’ created textural contrasts, mixing luxury fabrics with technologically-advanced and industrial materials. Lang’s more personal genre of minimalism and his preference to position himself as a ‘fashion outsider’ are now used to value his new output as a fine artist.

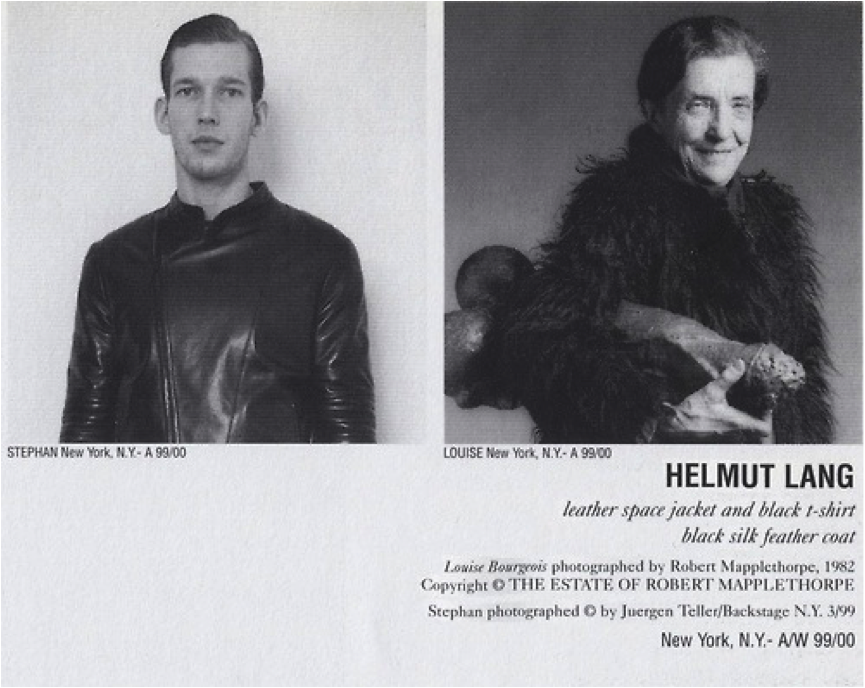

During his career in fashion, Lang kept the art world close by with various creative collaborations with stylists, photographers, architects, and contemporary artists, such as Louise Bourgeois and Jenny Holzer. In his campaigns, Lang frequently opted to juxtapose contemporary fashion photography and archival imagery. For his label, this became a means of distraction from the inherent commercialism of advertising, instead presenting his designs as artistic creations. This is exemplified in Lang’s campaign from the 1990s which used Robert Mapplethorpe’s iconic 1982 portrait of the artist Louise Bourgeois wearing a black monkey-fur jacket. In the campaign captions were used to grant authorship to Mapplethorpe though naturally the advertisement also included Lang’s logo, signifying that this very juxtaposition of images had been his curatorial act. The label’s New York flagship store functioned as the built embodiment of this minimalist aesthetic, lined with LED installations by Holzer and sculpture by Bourgeois, forming a crucial part of the architecture. Although his fashion designs were not unique objects, the space in which they were sold emulated a cultural and curatorial laboratory, actively creating ambiguity between commercial retail and gallery space. Symbolic value was core to this kind of marketing, which built on exclusivity and intelligence as a means of distinguishing itself from pure commerce and mass fashion. For designers such as Lang, this became a way to cultivate a status of high culture by borrowing cultural capital from art, thus maintaining a very direct relationship with his customers ‘in the know’.

Key to the various ways Lang presented his designs was an evident distraction from commercial elements, which led to an accumulation of symbolic capital to his label. This makes Lang part of a long line of fashion designers who were – and are – involved in sponsorship of the arts and engage with art through their marketing and retail channels. As a branding strategy, this enables a luxury brand to construct an artistic identity that contributes to an obfuscation of commercial operations. Although the stories about his New York shop have taken on mythical proportions, when it is placed into context it was not in fact a rarity as the minimalist spaces of contemporary art galleries had a major influence on store design during that period. Rem Koolhaas argued that minimalism even became ‘the “single signifier” of luxury, aimed at minimising “the shame of consumption”’.

Yet, while other designers – Miuccia Prada being one prominent example – never made it a secret that they were working as art patrons, Lang purposefully never positioned himself as a maecenas. Significantly, the tales told about and by Lang emphasise the symbiotic nature of his ‘more genuine’ collaborations for which he brought together a group of artists – who he also considered to be his closest friends. This narrative is closely linked to the cult status and nostalgia that is attached to Lang’s practise today and is no doubt tightly wound up with the fact that he is no longer a practicing fashion designer. For Lang, however, the latter became a valuable tool to introduce his new identity and to enter into the visual arts scene – a realm that, today still, is generally regarded as higher in the hierarchy of creative production.

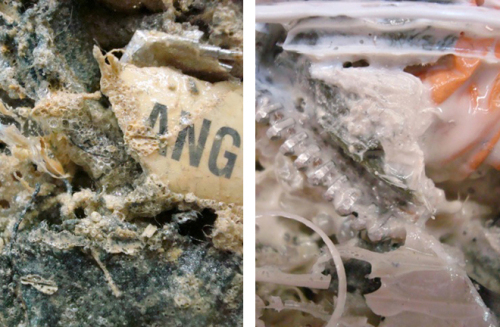

Lang showed ‘Make it Hard’ for the first time in 2011 at The Fireplace Project in East Hampton. The installation of columnar forms is made of 6,000 shredded pieces of clothing and objects from his burned archive, covered with pigment and resin. It appears like a geological scape, with the pillars dispersed in the room, each measuring between ten and twelve feet high. The title of the piece, ‘Make it Hard’, challenges the logic of fashion: first destroyed and then transformed into sculpture. The columns evoke his signature deceptive tactility as they are covered with resin, a liquid that hardens into transparent solids, causing the surface to simultaneously appear hard and soft. However, in the realm of the art gallery, fashion is re-contextualised from being something one is intimately covered in, into being something we are spatially surrounded by. The exhibition’s reviews discussed its deconstructive nature and recognised Lang’s characteristic attention to shape and materiality. These interpretations are hardly a surprise, as the columns are indeed fashion objects reduced to their abstract essence. This time, however, fashion itself became the ‘outsider material’ making Lang’s former profession present only in the parts of his printed label surfacing among the textures.

In 2005, Helmut Lang’s career as a fashion designer was brought to a conclusion. In fact, it is clear that Lang devised his own conclusion by creating tension between preserving and deconstructing his fashion past. Through ‘Make It Hard’ he literally and metaphorically brought together the different elements that had been crucial to his work as a fashion designer, while simultaneously destroying and ending them. For now – and despite his efforts to transcend his former practice – criticism of his legacy in fashion has become a rather easy reading of what might otherwise appear as a complex and enigmatic minimalist piece. But then, one has to ask, perhaps the case of Helmut Lang illustrates the need we still have for strict boundaries between art and fashion?

Elisa De Wyngaert is an Antwerp-based fashion historian and writer, graduate of the Courtauld Institute of Art, London.