Vestoj and Style Zeitgeist have teamed up in a dialogue and series of critiques of recent events in fashion media to raise more wide-reaching questions about the state of contemporary fashion media – and what that says about our industry at large. In the second instalment, we examine Jefferson Hack and Rizzoli’s recent book venture We Can’t Do This Alone: Jefferson Hack the System.

Vestoj and Style Zeitgeist have teamed up in a dialogue and series of critiques of recent events in fashion media to raise more wide-reaching questions about the state of contemporary fashion media – and what that says about our industry at large. In the second instalment, we examine Jefferson Hack and Rizzoli’s recent book venture We Can’t Do This Alone: Jefferson Hack the System.

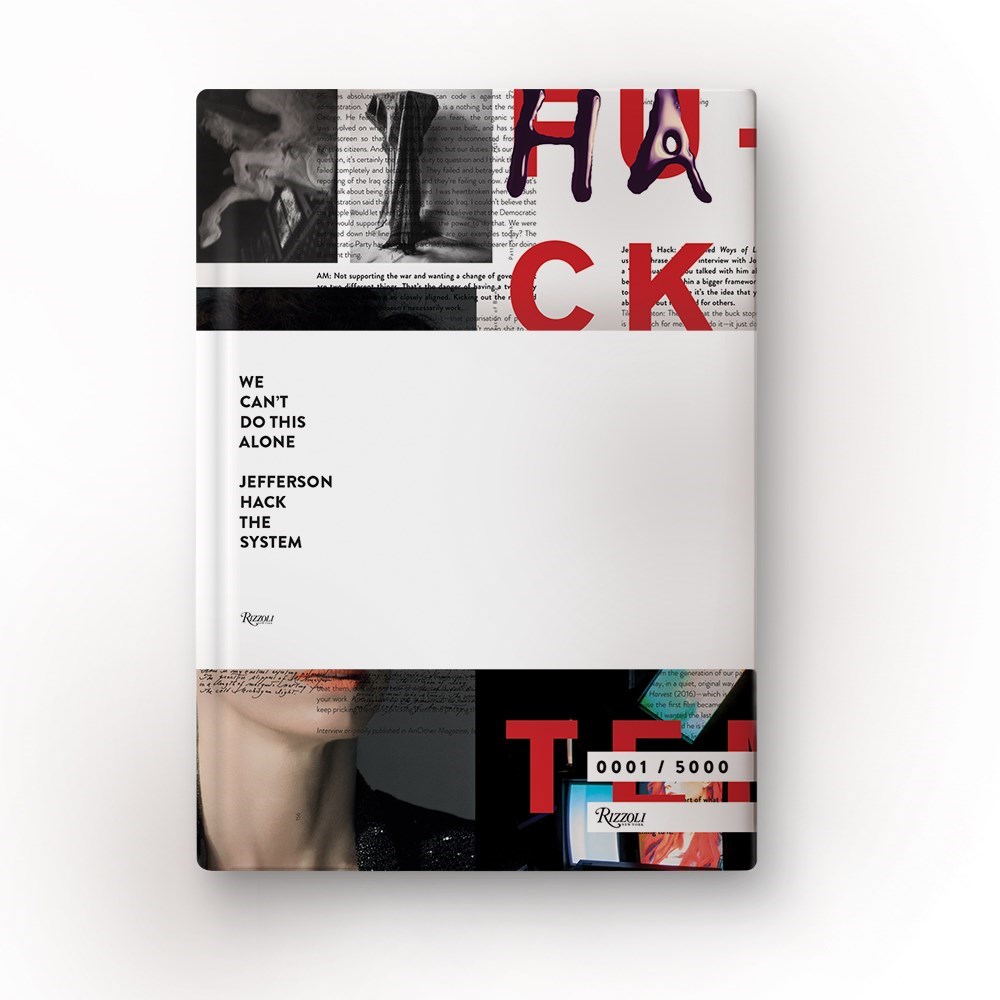

The press release for Jefferson Hack’s new book We Can’t Do This Alone: Jefferson Hack The System permeated fashion and design media these last few weeks. The monograph, released mid-May and published by Rizzoli, is a hardback, visually led selection of the editor and publisher’s work on Dazed & Confused magazine over the years.

As the author, Hack is presented as a fashion provocateur, moving easily across cultural categories. Concurrent with the book’s launch, Hack collaborated with French designers Each x Other creating T-shirts (stocked in Paris boutique Colette and priced €155 to €255) for their spring/summer 2016 collection. The T-shirts endorsed the book by referencing its title along with statements like: ‘The best way to make money is not to make any.’

The book’s contents select from Dazed & Confused magazine’s prolific body of work over its twenty-five year existence, adding to this, it features contributions from the high profile figures, like co-founder and photographer Rankin, musician Björk, actress Gwyneth Paltrow to artist Ai Wei Wei and novelist Douglas Coupland.

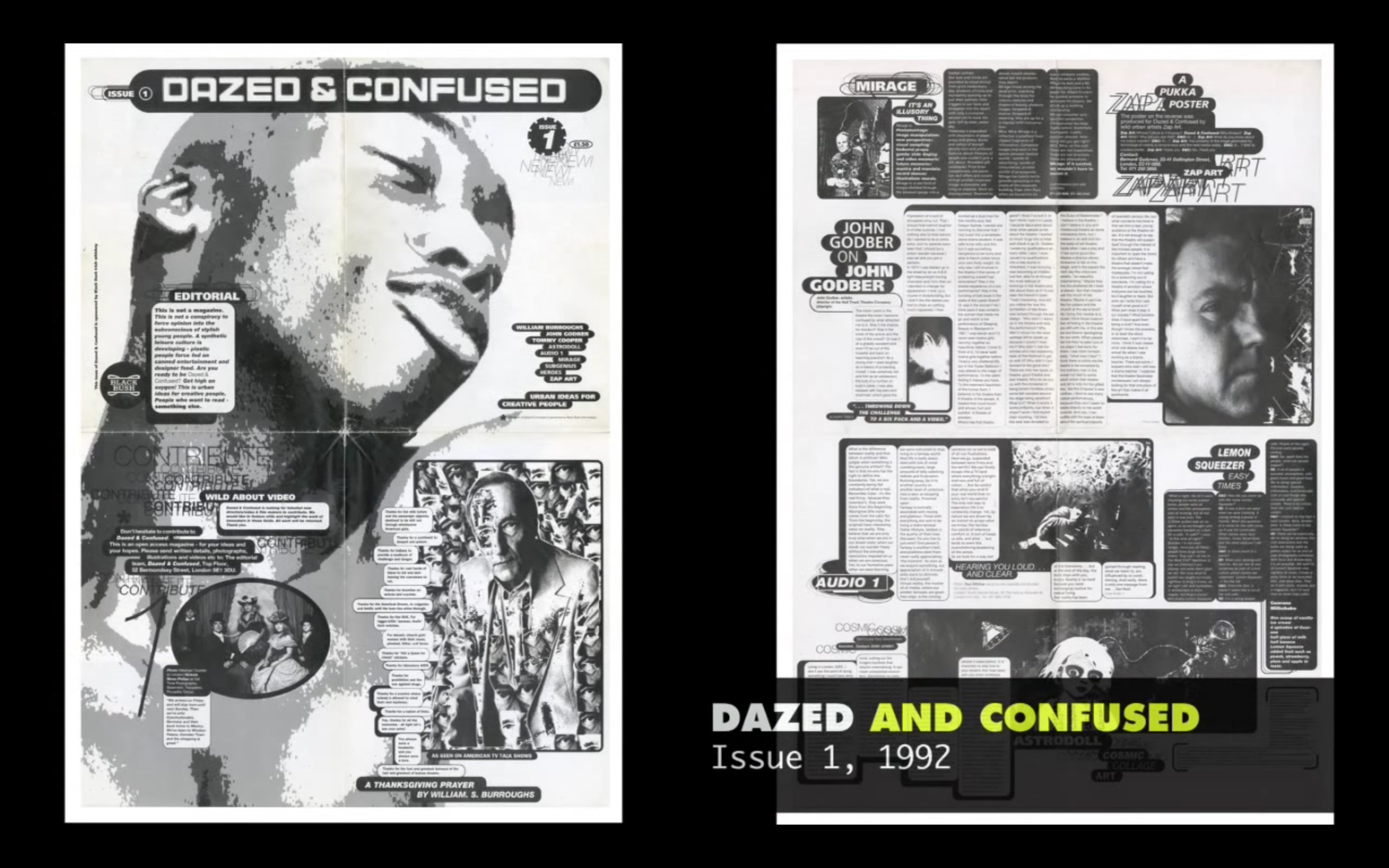

Since it was founded in 1992, Dazed & Confused has persisted through commercial and economic shifts in the fashion industry. It was initially conceived as a zine when eighteen-year-old printing student Hack approached photography student Rankin to create a publication to represent London’s art colleges as a collective. The project began in a black and white poster format, and its pages reflected the counter-cultural, DIY spirit of an era where cultural disciplines were beginning to break down and speak to each other more dynamically.

These early issues were highly influential in merging genres from fashion, music and art graphically on the page. Hack and Rankin, two bold students frustrated with the state of media in the creative arts, appealed to a young, culturally savvy, style conscious reader in reaction to mainstream glossies. The first issue reflected this spirit with its opening manifesto reading:

‘This is not a magazine. This is not a conspiracy to force opinion into the subconscious of stylish young people. A synthetic leisure culture is developing – plastic people forced fed on canned entertainment and designer food. Are you ready to be Dazed & Confused?’

– Dazed & Confused, issue 1 1991.

These counter cultural beginnings are essential to the branding of the global media company Dazed now operates as, and We Can’t Do This Alone attempts to project this energy. An opening essay by Hack reads as a call to action. He writes: ‘We are all media. We can rewrite the rules together. We have the power to construct our own language and distribute our own images.’ The tone is similar to Dazed & Confused’s initial issue, but the economic context in which it is written is vastly and fundamentally different.

The graphic approach to layout also echoes this paradox. Collated and designed by New York-based art director Ferdinando Verderi, the publishers worked with Kodak to produce a unique cover for each of the 5000 copies in the print run. No stranger to corporate collaboration, Verderi is a founding member and creative director of the ad agency Johannes Leonardo, whose clients include Coca Cola, Adidas and Trip Advisor.

Corporate dealings are home territory to Hack. As publisher and director of Dazed Digital, Hack oversees an editorial and media empire that now incorporates AnOther Magazine, Dazed Digital, AnOther Man, NOWNESS (funded by luxury conglomerate LVMH) as well as Dazed & Confused. On their website, Dazed Digital boasts global brands like Armani, Chanel, Nike, Swarovski and Dunhill as key clients. Given this, Dazed Digital is unequivocally embedded in the mainstream fashion system, making the political-sounding rhetoric and graphics of We Can’t Do This Alone seem empty to say the least.

In effect, the book is a corporate project dressed up in DIY aesthetics. Dispersed through its pages are hyperbolic, political-sounding phrases presented in graphic arrangements. One spread features the text, ‘A conspiracy of ideas’ in an artwork of haphazardly cut and stapled paper. The message is direct but fundamentally ambiguous: who the conspirator is, and how we, as readers, are supposed to deal with this ‘conspiracy’ remains unarticulated.

Hack’s claim as an independent publisher is equivalently hollow, prompting criticism from journalists on the commercial activity of the Dazed Group. Features on Hack in The Guardian and the Financial Times have addressed this.1. In a particular ‘Lunch with the FT’ feature for the Financial Times, John Sunyer mentions to Hack his ‘surprise at the amount of “content sponsored by brands” in his magazines, much of it passed off as regular journalism. Take, for example, the October 2013 issue, in which six pages are given over to Hack’s collaboration with Tod’s, the luxury Italian shoemaker.’2

When offered the opportunity to respond to these criticisms, Hack still doesn’t seem to be able to articulate a key distinction between independent publishing and corporate activity. In an interview with Lou Stoppard for SHOWstudio in 2014, she questions him on the commercial motivations of Dazed & Confused:

“When you started Dazed you talked about it being an independent magazine, […] but you yourself, and Dazed Group, doesn’t operate in an independent way, you’re very closely tied to advertising.”

“Independent doesn’t mean anarchist. Independent for me means we choose what we do, and nobody tells us what to do.”

“So your stylists don’t shoot full looks for advertisers then?”

“Of course they do. But I still decide what happens. What goes in and what doesn’t. We make all the decisions. And that’s independence.”

[…]

“Independence from what?”

“Independence from anybody telling us what to do. We do what the fuck we want to do. That’s independence. It’s that simple.”

– Interview with Jefferson Hack by Lou Stoppard for SHOWstudio in March 2014, https://vimeo.com/91950177

In her research on ‘niche fashion magazines’ fashion scholar Ane Lynge-Jorlén cites Dazed & Confused, among others as part of a genre of magazines that although aesthetically is ‘positioned outside the mainstream, their financial underpinning is advertising revenue, and they are thus, not outside commercial interests.’3 Dazed & Confused’s implicit relationship with big corporations, despite claiming an independent status, functions as a brand extension for the luxury fashion companies it features in ‘full looks’ on its pages; a relationship that symbolically and economically reinforces the brand value of both parties in the contemporary market.

Under the umbrella of Dazed Digital, a content and media producer for corporate brands, Hack capitalises on the cultural clout generated from Dazed & Confused’s heritage as a counter culture publication. Yet, fundamental changes in the way this publication operates in the commercial market indicate the magazine’s shift from being an independent publisher to a media agency, making press release statements like ‘If you stand for nothing, you’ll fall for anything,’ dangerously hollow. Stoppard querying Hack about ‘Independence from what?’ is a critical question in defining a position in relation to the commercial high fashion system, and Hack’s oblique answer points to the difficulty of appearing ‘authentic’ while simultaneously being transparent with your commercial motives.

In his failure to answer his critics, Hack, not surprisingly, appears unable to demonstrate what exactly needs to be ‘hacked’ in the fashion system. Apart from a light-hearted pun in its title, how to meaningfully subvert the system that he has become a leading tastemaker of, is a question his book raises but fails to answer. Instead, it falls amongst the many voices that harp on about the sorry state of the contemporary fashion industry, without wanting to acknowledge the role they play in constructing and upholding it. The end result is just more white noise.

Laura Gardner is Vestoj’s former Online Editor and a writer in Melbourne.

see Eva Wiseman (2011), ‘Still Dazed at 20: the gang who changed pop culture’, The Guardian, http://www.theguardian.com/media/2011/nov/05/dazed-confused-gang-still-cool, 6 November, 2011 ↩

‘Lunch with the FT: Jefferson Hack’ by John Sunyer for the Financial Times, 8 August 2014. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/2/fc444a8a-1cab-11e4-88c3-00144feabdc0.html ↩

Ane Lynge-Jorlén 2012, ‘Between frivolity and art: Contemporary niche fashion magazines,’ Fashion Theory, vol. 16, issue 1, pp. 7-28, Berg, Oxford. ↩