A man I know once sat next to Yves Saint Laurent at a Paris dinner party. He asked, “What portion of Yves Saint Laurent revenues are accounted for by perfume?” Saint Laurent replied, “Eighty-three point five.”

Chandler Burr, The Perfect Scent: A Year Inside the Perfume Industry in Paris and New York, 20071

FRAGRANCE PLAYS A PIVOTAL supporting role for fashion companies by offering a democratic way for consumers to buy into an otherwise unattainable luxury brand. Fashion houses thrive, even depend, on something as seemingly transient as a bottle of perfume, and Yves Saint Laurent’s words remind us just how acutely aware designers are of this potential. Indeed for an industry that has annual worldwide revenue of $27.5 billion (a figure that is set to increase to $45.6 billion in five years time), it comes as no surprise to the CEOs either.

Garnering the potential for revenue, advertising budgets for fragrance are as substantial as those of the fashion products. Baz Luhrmann’s three-minute long production for Chanel starring Nicole Kidman, ‘No. 5 The Film’, set a precedent in 2004 with its $42 million budget. Meanwhile Dior enlisted actress Natalie Portman to front their Miss Dior advertising campaigns, a partnership that is reflective of the proliferation of celebrities and fragrance.

As a marketing strategy, film offers fragrance products an immersive tactility, that is unavailable in traditional print advertising. Film creates a ‘feel’ of a fragrance and expands on the olfactory narrative by combining sight, sound and visual texture. In Sofia Coppola’s ‘La Vie en Rose’ for the Miss Dior perfume, the sight of Portman (dressed in Dior haute couture) laying back onto a lush bed of roses presents a multi-sensory evocation; the creamy feel of the petals against the skin, their delicately wafting floral scent, suggests romance. Brands therefore activate not only the consumer’s desire for a new fragrance, but a desire for a meaningful fragrance. Through their sustained concept of narrative, fragrance films offer the opportunity to engage with the values of a brand like Chanel or Dior, without buying the clothes. Furthermore, the potential to release films on the internet allows a more prolonged and widespread exposure to the product than seasonal print advertising.

As part of the fashion system, fragrance, like clothing, is subject to trends and commoditisation. For example, the rising popularity of Arabic-inspired fragrances like Armani Privé’s ‘Oud Royal’ or Tom Ford’s ‘Oud Wood’ is linked, as Saeed Kamali Dehghan argues in his article for The Guardian, with the growing Middle Eastern luxury consumer market, a trend that ultimately reinforces the consumer’s desire for the rare and exotic.2 Though the pace of the fragrance industry may be slower than fashion, scents follow a clear trend cycle. The structure of the trend cycle, as sociologist Everett Rogers proposed, group consumers as either early adopters, early majority, late majority, laggards and non-adopters. While one can identify these themes readily in fashion, the lack of visibility for fragrance makes it more difficult to define such categories. Fragrance does not carry the overt visual status symbolism on the body that clothing allows and therefore is not driven by the same urge as sartorial purchases. We also engage with fragrance in a more physical and intimate way, making our desire to consume them, at least for the most part, a more carefully deliberated purchase. Thus, trends in fragrance develop and last for a longer period of time, resulting in a delayed trend curve.

While fragrance on a consumer level is slower paced than fashion, it offers a higher source of revenue. As ‘fragrance expert’ Michael Edward notes in his book, Fragrances of the World 2013, within ten years the number of yearly fragrance releases increased from 132 to 1,432. The fragrance industry, it seems, is speeding up.

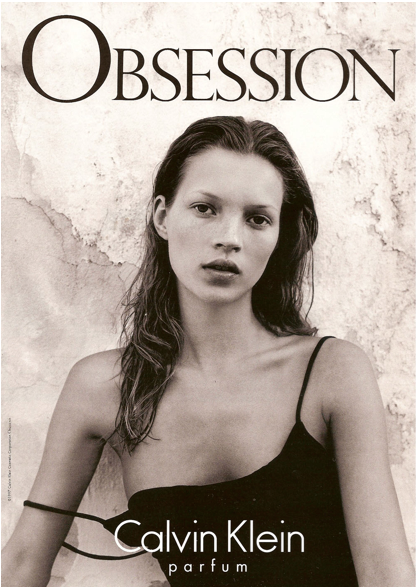

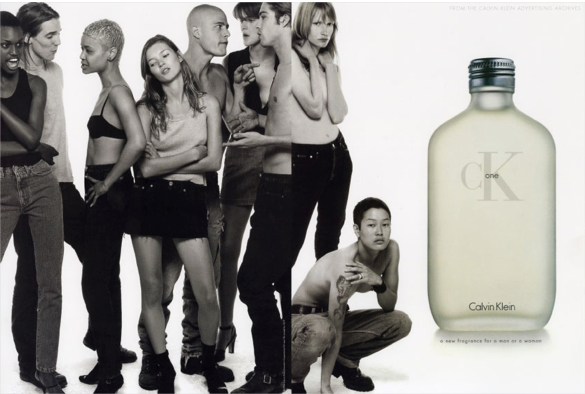

Professor Barbara Vinken notes that, ‘the time of fashion is not eternity, but the moment’. If fashion is about the moment, the whiff of a fragrance qualifies as a fragment of this moment in time. Scent manages to be more fleeting and ephemeral than fashion, its impression only lasting a few seconds at a time to the beholder of the wearer. To counteract this, fragrance advertising often presents an eternal identifier of a period’s zeitgeist, much like fashion. A keen example of this is Calvin Klein’s CK One campaign shot by Steven Meisel starring a young Kate Moss in 1994. We see minimalist fashion, a grungy setting and the general ambivalence that defined Nineties fashion. Olfactorily, the citrus aromatic fragrance with notes of lemon, jasmine and musk similarly reflects the era, and its transparent scent and unisex appeal perfectly coincides with the decade’s waif aesthetic.

According to professors Marie-Pierre Fourquet-Courbet and Didier Courbet, ’perfume is an “olfactory identity card” that becomes an inherent component in the individual’s social and narcissistic identity.’3 As long as identity is in a perpetually transitional state, so too will trends in fashion and fragrance progress. Trends are therefore an essential component of identity formations.

Like fashion, the fragrance industry is anchored in the possibility to form identity, and as such, it is subject to a trend cycle. Within this structure, both mediums find themselves in a constant state of flux, pursuing the tastes and desires of a singular moment in time. While perfume may mimic fashion in terms of its industry structure, it engages more broadly with consumer psyche. This marketing potential, and accessibility, makes fragrance a crucial business component of the luxury fashion market; not every consumer can afford to have these brands’ garments hanging in their closet, but a larger majority is likely to have their perfume sitting in their bathrooms. The longevity of fragrance offers an opportunity for a long-standing customer connection. While the clothes season regenerates, the branded fragrance remains available at the beauty counter for years.

Carla Seipp is a freelance fashion, arts and fragrance journalist.

Burr, Chandler. 2007. The Perfect Scent: A Year Inside the Perfume Industry in Paris and New York. New York: Henry Holt and Company. p. xvi ↩

‘Perfume brands get whiff of profit from Arabian scents’ by Saeed Kamali Dehghan, 8 June 2012. http://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2012/jun/08/perfume-brands-profit-arabian-scents ↩

Courbet, Didier and Fourquet-Courbet, Marie-Pierre. Perfume Advertising and Marketing: Evolution and New Trends. Perfume: A Global History. edited by Marie-Christine grass. 2007. Paris: Somogy Art Publisher. p. 255 ↩