We talk on a bench by the Jacob Javits Convention Center. It’s a glorious summer day, and he’s here to work. He speaks of his long career providing security for gallery openings, fashion designers, ladies who lunch and, later, for New York Fashion Week with a candidness that is totally disarming. I drink my coffee and listen while he looks through the big stack of files he’s brought with him, and reminisces about what fashion once was.

Forty years ago I was a detective in New York City, but you never make enough money being a policeman you know. You have to supplement your income as a civil servant, so many of us did security work on the side. It’s called moonlighting. My first job was at a cocktail party in an art gallery; I made a crisp fifty-dollar bill in an afternoon. That was a lot of money for me back then. What did I make? Say $20 000 a year? And all I had to do was stand at the door with a guest list and make sure that no one got in who didn’t belong. It was all very innocuous, there were never any issues really. Every once in a while a homeless person would come by, look through the window and see somebody serving trays of hors d’oeuvres and try to come in but that was about it.

I started my company a year later, in 1981. My reputation spread through word of mouth mostly. Alongside gallery openings I did these high end cocktail parties on Park Avenue in people’s residences. I remember noting that most of those women, the dowagers, had very big feet, and telling my wife about it. Getting to know my fair share of ladies who do lunch, as they were called back then, helped when I started working on fashion events. Many of those ladies with big feet would come to the shows too. I knew them by face which was helpful since nobody would bring their invitations to the shows back then. Their face was their invitation. Typically, they would just walk through the door, with a ‘how could you not know who I am’ expression, and I did know who they were. I still do.

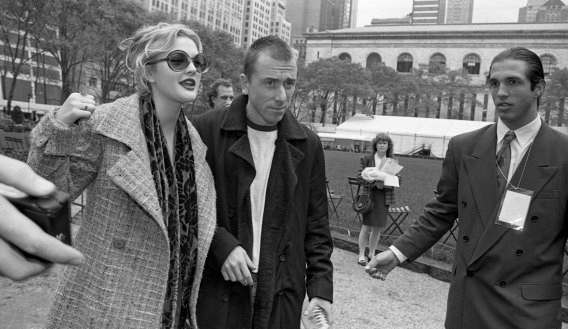

Anyway, I get ahead of myself a little. I did a lot of AIDS related fundraisers in the Eighties. I worked with Norma Kamali for her shows and her boutique, and eventually that led to a job for Valentino in the early Nineties. That was a very big job for me. He literally built a piazza on Park Avenue, and called it Piazza Italia. The right people saw me working there, approached me and said that they were going to erect tents in Bryant Park to host fashion shows. I was asked to put a bid in on the job, and I did. I got the job, and the first official New York Fashion Week shows at Bryant Park opened in the fall of 1993. I learnt a lot about fashion from the get go. When the shows are on, you’re immersed in it for eighteen hours a day. It’s very very demanding, and you need to be focused on it.

NYFW has grown so much. In 1993 we only had twenty-seven shows, but last time I was involved we had ninety – that’s almost four times the amount. The venues in 1993 held four hundred people, now they hold 1500. Overall, now we shuffle over 100 000 people into various fashion shows for the duration of fashion week, and this needs to be done in a civil manner. These people are very sensitive, and they cry very easily. I’ve dealt with tears and with tantrums. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve heard ‘I’m with her, she’s with me,’ or ‘don’t you know who I am.’ They’re all legends in their own minds.

We practice what we call ‘security with a velvet touch.’ We stay in the shadows. The PRs check people in, and most of them don’t know what they’re doing but that’s another story. Anyway, we stand behind the PR people. If we see them lingering with an individual, we might catch the individual trying read the guest list. People do that you know – they can read upside down. If we see that one of these PR persons is taking more than a minute or two with someone, then there’s usually a problem. PRs are often afraid that if they bar someone they’re going to lose their job. Meanwhile, they could also be letting in the wrong people; someone might use your name to get in, and then when you show up five minutes later I won’t let you in since you’re already here. Imagine – that’s a whole scene. Basically, we play the bad cop. But we always try to give people a gracious way out, like, ‘Sorry you’re not on the list, obviously there was an issue with your invitation, maybe you didn’t RSVP in time?’ You never say, ‘Oh get outta here,’ even though you want to. But you can’t, because like I said they cry very easily and you never know who they know.

Only certain people on my staff can do fashion. I’ve learnt to be a good judge of that. To work at a fashion event, number one: you need to look good. And you need to speak well, you need to follow instructions, you need to stay focused, and you need to know who’s coming in the door. You need to know the Anna Wintours. You need to know the first, second and maybe even some of the third row people. Anybody above the third row is in Siberia – they’re somebody’s Aunt Tilly. We need to take care of the first, second and third row. Those are very important people. I keep track; I have photos of everybody. They are posted on our door, and when my staff leave the office they see them.

I’ve been fortunate enough to count about three quarters of my staff as regulars – they’re policemen, they’re firemen, they’re postal workers, they’re ex-army. They come back twice a year and they become more familiar with who’s who. It works out. I don’t hire people who just have a big neck, you know. If you give me your resume and tell me you’re a judo guy, that’s the last guy I’m going to hire. I can’t have that. I don’t want you to be using those skills, or to show me that you can knock somebody across the room. I don’t have that kind of clientele, and I don’t want that kind of clientele. Dealing with the public is so important. It’s like a ballet – you take this part and put it over here. ‘Now what’s the problem? You’re not getting in, is that it? I’m sorry, that’s the score.’ These fashion people are not stupid, they look and they see and they listen. I mean if too many guests tell the designer they had a problem coming to their show, the designer won’t be coming back to us.

We are typically the ones who have to tell people when the show is overbooked and they’re not getting in. They don’t love us then. ‘That’s stupid, how could you do this?’ Well, we didn’t. The designer did. But someone has to be the bad cop, and that someone is us. Stanchions are our best friends in those situations; they allow us to channel people properly, ‘Standing room is to the left, seating room please go right in.’ You have to always let the public know what’s happening, don’t ever keep people in the dark even when the news is bad. Tell them, they want to know. Nobody wants to stand around like a lamp post. I’ve been doing this twenty-five years now, I know the drill. I’ve made a lot of friends over the years, and probably a lot of enemies too. There are some people who just won’t give up.

I’ll show you my archive. I’ve saved everything from every season since 1993. Look, this is me with no grey hair – can you believe it? I had to institute a rule early on, that all my staff had to be in black suits. I can’t tell you how outrageous the suits people turned up in were. And the ties – oh lord. People thought that because it was fashion, they could turn up in a tie with pineapples on it. That was not ever going to fly. Now everybody has a black suit and I give everyone a tie.

I remember the first show during that first Bryant Park fashion week. October 31, 1993, Donna Karan. Donna invited Barbara Streisand, but Barbara Streisand was late. The show was supposed to start at one o’clock. At one thirty Barbara Streisand still wasn’t there so Donna started the show. Who shows up five minutes later? That’s right, Barbara Streisand. And I had to go ‘Barbara’s here! Barbara’s here!’ So what they did is they stopped the show, and then they started it again.

There was a time when people were literally slicing open the tents to sneak in. We had one young lady covered in mud one night – this was a season when it rained all week. I caught her sliding under the tent. I said, ‘This is a fashion show, what are you doing?’ ‘I have to see it, I have to see it!’ ‘Well you’re not gonna see it now anyway let me tell ya that.’ We’ve had people replicating invitations, we’ve had people impersonating others. If they knew a journalist was out of town they would come in and use the journalist’s name – this is another reason we need to have facial recognition. There are so many different ways you could try to sneak into a show. Now we have people selling tickets on the net. I remember a mommy and daughter who flew in from Texas. They were in town for fashion week for three days, and they had four tickets in their hands for the most popular shows that season. None of the tickets were valid. The first show they tried to get in, ‘Bingo!’ ‘Where did you get this ticket?’ ‘Well I bought it on Craig’s List, and I have three more.’ We accommodated them in some way because they already spent airfare, hotel and $3000 to buy four fake tickets. These people don’t know.

Did you hear about the lady that died on the runway? This was about five-six years ago – her name was Zelda Kaplan, and she was ninety-five I believe. She was sitting on the first row, second seat at the Lincoln Center. Zelda was a fashion icon for years, always dressed to the nines. She was with her escort who was sitting behind her, a younger gentleman. All of a sudden Zelda does this – puts her head down like this, so her friend grabs her shoulders, he realises something is wrong. This is when we take notice, and can you believe it – she’s dead. But the show is still going on. So we cross over as discreetly as possible and pick her up. We cross the runway, carrying her, and we bring her outside and of course the medics are there, trying to revive her. The show never stopped, and most of the people never knew what happened because they were looking the other way. Afterwards of course this makes the newspaper. Death and fashion, they love it. New York Post is having a field day. All everybody wanted to know was, ‘Is she dead?’ Well I’m certainly not going to give away your medical information, so all I said was, ‘There was a woman at the show that needed medical attention, and she was taken to the hospital.’ If there’s an upside, it’s that Zelda Kaplan had been coming to fashion shows all her life. If she would have scripted it, it couldn’t have been done better. She made her exit the way she lived. Anyway, that’s the Zelda Kaplan story.

There were always a lot of people at Bryant Park in the early days: we would refer to them as lobby fleas. They would come in in the morning because they had an invitation to a show, and they’d never leave. They’d spend the day, people watching, just to see who’s there, just to be seen. You couldn’t get rid of them. The lobby would be filled with all these people, if it was cold or rainy, forget it they never left. Fashion people can be fanatical, but then again so are people at football or baseball or basketball games. It’s not every show though; out of eighty shows, seventy are fine. Only ten are ‘I gotta get in’ type shows. Nobody’s breaking into a show at nine o’clock on a Sunday morning. And then if it rains, you’re embarrassed for the designer. You don’t want that to happen. Sometimes we have to sit in as seat doubles; we sit in the front row and pretend to take notes.

Every day, I read the fashion weeklies. I subscribe to People magazine. I don’t read it, I just look at the pictures because I have to know who the next hot starlet is, you know, who the next guy is going to be, because they come to these shows and they sit in the front row. Sometimes a PR person will come up and say ‘I have a talent person with me and we need some special treatment.’ It means they need to go in a certain door, or they want to go backstage so we accommodate them, we do. Sometimes the designer doesn’t want to take a picture with a certain person, and then we have to make sure that never happens. I can’t mention any names but there was one designer who said absolutely not, and she knew that this individual wanted their picture taken together. And of course there are some people that want to sit next to Anna and have their picture taken. We make sure that the appropriate people are sitting next to Anna, not just anybody.

After working with NYFW for twenty years, Anna Wintour said hello to me. It was about ten years ago now. I thought I must have been mistaken, she must have thought I was somebody else. I asked around and was told that she knew exactly who I was. So now it’s ‘hello’ always. She often comes an hour before the show, and sees it alone – before the public. Then she comes through the back door and we bring her in. When that happens, I walk next to her but otherwise I very rarely am backstage. We only allow female security backstage. They make sure that the photographers aren’t taking inappropriate photographs at certain times, right, which we find they try. They make sure that there’s nobody back there that doesn’t belong, you know stagehands, the lighting guy – they don’t belong back there, the models are getting dressed! We also keep the public at the end of the show from charging backstage. Wait two minutes will you, let the models at least get some clothes on. Often the PR people will have some celebrity that they want to let in before the others, someone the designer wants to take a shot with. The word is always, ‘The clothes were fabulous.’ It’s the only word they ever use – ‘fabulous.’ Already in 1993 that was the word. ‘Fabulous, fabulous, fabulous.’

Anja Aronowsky Cronberg is Vestoj‘s editor-in-chief and publisher.