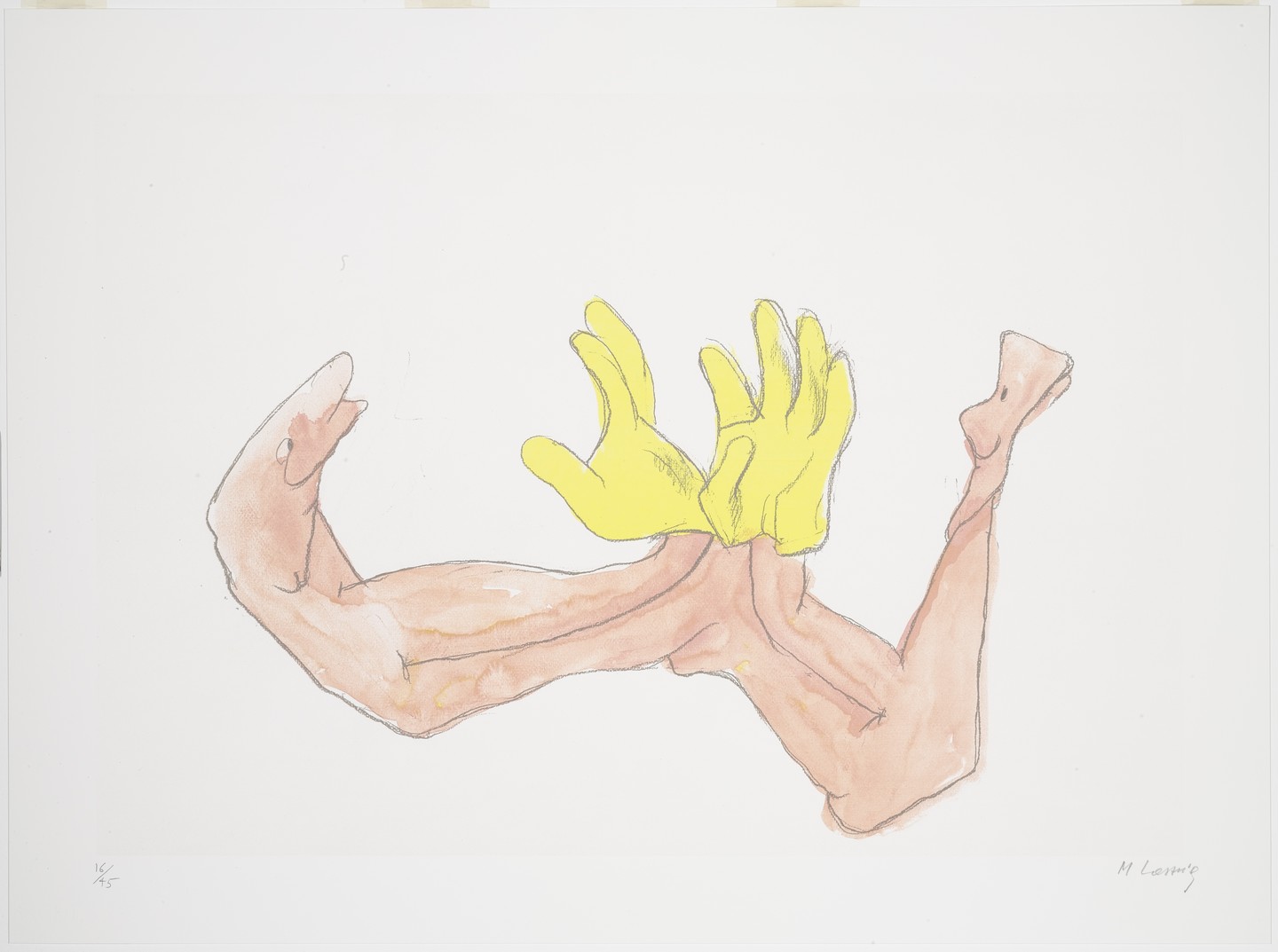

‘All disgust is in origin disgust at touch,’ philosopher Walter Benjamin aphorised under the theme of ‘Gloves,’ locating the point our repellence towards animals begins.1 Disgust of something is, first and foremost, a visceral response to the possibility of touching it. The sight of discarded gloves has become familiar to me during my walks in London, so too the guarded look of an oncoming runner nearing a corner at speed. Methods of demarcating bodies, like gloves, masks, and clothing, have gripped our collective attention in the world around us.

Being in physical contact reminds us where our selves and the other begin – the by-product is an experience of estrangement. If I am disgusted by an image, I am ‘touching’ whatever it is lodging in my psyche. Disgust, especially now, seems to be channelled through our hesitance in physical touch, but also in alienation against the status quo of the present. It moves beyond its use as an emotional reaction to tell us what kind of future we do or do not want.

For many of us, Covid-19 has wordlessly twisted the boundary of what can be touched or not, so much so that touch itself has turned into a vaguely clandestine act. Who or what we touch becomes political and the ramifications heightened – and therefore pleasure and disgust too. Worldwide cancellations of fashion weeks, catwalk shows, and the projection of an immense recession threatens to swallow a whole swathe of the fashion industry. But you know this.

Turning Benjamin’s aphorism on its head, it could be said that all pleasure is, in origin, the pleasure of touch. This twin drive emerges when we think about all the things it is possible to touch and the fact that all of us have been driven to this virtual space as the physical spaces we are accustomed to are no longer within reach. The disjuncture that has emerged in lockdowns worldwide between our physical realities and other realities – streams, in-game, video chat, and elsewhere – has meant that we have also spent an increasing amount of time simultaneously avoiding touch but being touching in other ways.

During the all-virtual Shanghai Cloud Fashion Week, the first fashion week to adapt to new prohibitions on mass gatherings, Angel Chen presented her A/W 2020 show via livestream.2 The physical models still walked, but the environments varied: from pale pink snow fields to red neon text illuminations redolent of sci-fi movie aesthetics by making use of a green screen. The wait to physically handle the clothing was abbreviated: since it was hosted on an Alibaba-owned platform, users could immediately order looks they liked. Whereas in the current climate, going to a store to buy clothing is loaded, suddenly, digital catwalk shows are no longer a facsimile of the present.

The digitisation of the catwalk has been foretold many times over. Yet, in the last year or so, a new category, digital fashion, has been heralded as one means of transfiguring the present into the future. Clothes are created in 3D modelling software that allows the result to be rendered and distributed online. A purchaser turns their body into a green-screen, allowing the proportioned 3D models to be swapped on and off, giving the illusion of being dressed in the garment. Minimal waste is produced. It is in the vernacular of a new demographic who spends most of its time online. A certain magic emerges in the way that clothing is conjured from the immaterial and our attention cannot help but turn towards it.

Naturally, countless media outlets have documented the immense hype of the application of 3D technology to clothes. The physical limitations of a show, catwalk, model, or audience no longer applies; the physics of the real world are merely a point of reference. The cultural implications, however, are still grounded in the present moment. In 2019, The Fabricant, the ‘first digital fashion house’ sold a digital dress for $9,500 on the blockchain meaning the purchaser had exclusive rights to have the dress digitally fitted to her photographs.3 Digital clothes, then, are asynchronous. It is only possible to wear the clothing by seeing yourself wear them. Last year, iD magazine produced a documentary highlighting influencers who are excited by the inclusivity of digital clothes to fit body types usually excluded from the mainstream, but also stimulate more engagement more quickly from followers.4 For all the prowess that this powerful technology presents, it seems for now the actual use of it is limited to creating photographic representation to be circulated in search of social and cultural value.

It could be easy to dismiss digital clothing as a poor replication of physical clothing or, more strongly, as part of the alienating aspects of disgust. A future in which we must circulate primarily online, led principally by the caprices of corporate-owned platforms, would provoke a reaction of disgust in many of us. As our attention has already been commoditised on platforms, self-representation would too. If digital fashion is an industry predicated on technological determinism, alienation from voices who suggest an alternative outside the bounds of this world is nearly inevitable.

This potential for alienation is particularly visible when witnessing the formal constriction of clothing, only visible on a 2D plane in social networks in which influence is already commoditised. Does this originate in the elimination of the tactile qualities of cloth, of fabric, and the sensuous pleasure of seeing clothes move in time and over time? Digital clothes can remain new forever, but by bypassing the wear and tear of physical clothes, do digital ones elide something fundamental? By being unable to touch, to feel, to smell, to apprehend, digital clothes are largely a visual experience above all else, affixed to still photographs. If pleasure is no longer found, does disgust naturally enter? Perhaps not, but disgust may play a role not just in the apprehension of a garment but in the systems and assumptions it represents.

I feel more estranged from physical touch than ever before and yet, by slowly discerning its outline, I am compelled by my encounters in the nascent world of digital fashion. The anthropologist Michael Taussig explores the question of touch in his 1991 essay, ‘Tactility and Distraction’, by way of Walter Benjamin’s concept of optical tactility.5 In Benjamin’s eyes, Dada architecture ‘hit the spectator like a bullet, it happened to him, thus acquiring a tactile quality.’6 Similarly, film was able to dissuade itself from replaying reality as it began to manipulate itself with new meaning-making techniques. Through extreme details, close ups, or juxtaposed cuts as its visual language, it transformed what it represented. What emerges is a certain way of touching; a visceral response to an image rather than a purely ocular one.

Though most offerings of digital fashion currently are worn via still photographs, the ultimate goal of most technologies purporting to recreate reality online is through motion and embodiment. Though virtual models may walk or pose as if on the catwalk, other endeavours attempt to remove physical references as a starting point altogether. Selfridges 2019 campaign with artist network, DIGI-GXL, embeds digital clothes within a custom 3D world on an enigmatic and faceless avatar.7 However, the full expression of the self is truncated. Animations rely on rigging models to predefined movements which work well for replicating the catwalk or advertising films. Improvisation of movement, of the kind that is possible when wearing physical clothing, eludes us for now. What can I make of this? I am removed from the texture of the garment but there is a feeling that I can apprehend the garment in other ways: the individual garment is part of a larger world that, unlike digital catwalk shows, is built without referent to the physical world.

For Taussig, the concept of ‘optical tactility’ is revelatory and explains exactly what kind of magic is being performed. By ‘rewiring seeing as tactility, and hence as habitual knowledge, a sort of technological or secular magic was brought into being and sustained.’8 Instead of the critic’s individual eye analysing a scene, we see together as a collective public whose everyday lives are increasingly constituted visually. During my walks in the past few weeks, I notice details less and contrast more often, reading my field of vision primarily by texture.

To our collective eye, digital fashion amplifies, shifts, distorts, and transfigures the physical cues of clothing. 3D artistry and animation creates a technological magic that is potent and discernible only at the surface. This magic operates on us as we go through the day, especially nowadays, distracted and hungry for touch. And what happens if seeing-as-touching induces both pleasure and disgust? Turning to the artist Frederik Heyman’s imagery, I see the enchanting aspects of technology and its propensity to overwhelm our sense of optical tactility.9 His work shows strikingly posed bodies, rendered in uncanny human flesh, against a backdrop of speculative machinery or animals. Heyman, who has collaborated with Y/Project, Gentle Monster, and most recently Arca, takes as a starting point our natural disposition towards simultaneous pleasure and disgust. Gazing on Heyman’s digital bodies, repulsion and curiosity immediately flood in and begin to synchronize. Soon it is clear that there is a technological mesmerism at play, rendering scenes that are uncanny somehow familiar. Here, it feels technological mesmerism is doing its work in transforming my eye into something that, above all, touches.

Optical tactility gives us the potential of both pleasure and disgust when considering digital fashion. In the current moment, touch seems to signify our own alienation as well as a hope in the future of new forms of sensory engagement borne out of necessity. The enchanting technologies behind all this give us the prospect of disgust and pleasure, but is only actualised in the everyday space that we find ourselves in online. It will be critical to understand and critique the shape the future takes in these spaces, allowing for both dislocation and accord. The absence and presence of touch is felt more strongly right now and, for digital fashion, it will continue to be at the centre of it.

Riana Patel trained as an anthropologist in Oxford, focusing on the political and cultural aspects of technology. She now works as a digital producer and researcher.

W Benjamin, One-way street. Harvard University Press, 2016. ↩

KALTBLUT Magazine. ‘ANGEL CHEN AW20: REALITY CHECK’ Youtube. April 29, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uA7Sb5QS09A ↩

https://www.thefabricant.com/iridescence ↩

i-D. ‘Will You Be Wearing Digital Fashion In The Near Future?’ Youtube. May 31, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=44p44FnOKE8 ↩

M Taussig, ‘Tactility and distraction,’ Cultural Anthropology 6.2 (1991): pp 147-153. ↩

Ibid. p.150. ↩

https://www.selfridges.com/GB/en/features/articles/the-new-order/meet-the-artist-digi-gal/ ↩

M Taussig, ‘Tactility and distraction,’ Cultural Anthropology 6.2 (1991): p. 151. ↩

https://frederikheyman.com/ ↩