We seldom stop to think that we are still creatures of the sea, able to leave it only because, from birth to death, we wear the water-filled space suits of our skins. —Arthur C. Clarke

He that can swim, needs not despair to fly; to swim is to fly in a grosser fluid, and to fly is to swim in a subtler. —Dr. Samuel Johnson

There is no such thing as bad weather, only bad clothing. —Old adage, source unknown

ONE OF SEVERAL SO-CALLED Analog Missions, NASA’s Extreme Environment Mission Operations (NEEMO) program is housed by the Aquarius Reef Base undersea research facility sixty feet below the Atlantic Ocean, sited 6.2 miles off the coast of Key Largo, Florida. Used as a condition chamber, training facility, laboratory and experimental habitat to prepare international crews of ‘aquanauts’ alongside engineers, scientists and ‘habitat technicians’ for future deep space missions as astronauts (literally ‘space sailors’), the underwater environment provides the most ‘convincing analog’ on Earth for the experience of spaceflight. A NASA spokesperson riffs on this analogy of alien similitude: ‘Much like space, the undersea world is a hostile, alien place for humans to live.’1

The implication that conditions composing ocean space are more extraterrestrial than terrestrial finds further visual kinship in the design of early diving suits, which, being exaggeratedly cumbersome, actually resemble the self-regulating ‘habitat apparel’ of the space suit, a garment lived-in aboard spacecraft. Indeed, as in deep space, we are literally not suited to survive underwater, because we cannot breathe; we must instead don prosthetic, dressed environments to make habitable normally uninhabitable terrains. We require dress that doubles as habitat, in the truest sense of Latin habitare for ‘to dwell.’

Iconographies of underwater pursuits and their accompanying imaginaries find frequent form in fashion: in Alexander McQueen’s Atlantis collection (Spring/Summer 2010), which featured his iconic ‘Manta’ dresses, digitally printed to conjure piscatory flesh, like armoured underwater camouflage, and even in his mussel shell bodice (Spring/Summer 2001), a corset dripping in shells. These creations make sense given that McQueen was himself an avid scuba driver who frequented deep-sea haunts in the Maldives. Some years later, former McQueen-intern Iris van Herpen’s Aeriform couture collection (Autumn/Winter 2017) took inspiration from Danish underwater artists Between Music, whose conversations with deep-sea divers, physicists and neuroscientists inform the sonic compositions and custom-designed instruments that enable them to perform in underwater environments. During her show, Between Music played with ‘liquid voices’ from inside illuminated tanks along the catwalk as models emerged, dry, in striking aerial counterpart — in tune with Van Herpen’s desire to frame the membranous ‘natural relationship between our bodies and the elements.’2

If our knowledge of the undersea world is indebted to diving, then it is also indebted to the habitat apparel of deep-sea diving dress. The spheres of activity joined together by the practice of diving are webbed and vast, entangling the ancient art of pearl diving and spearfishing, histories of ornament, and the emergence in the eighteenth century of the discipline of natural history — a discipline that built itself, at least in part, upon dredged-for specimens from the sea floor that found subsequent display in in-vogue wunderkammers. Oceanographic exploration, undersea archaeology, military and naval operations, too, and the very visual culture of underwater rendered vividly in photography and on film, are all commensurate with wearable diving technologies. Diving excursions recounted in Beneath Tropic Seas: A Record of Diving Among the Coral Reefs of Haiti (1937) led naturalist William Beebe to call for ‘a whole new vocabulary, new adjectives, adequately to describe the colors of under sea,’ in counterpoint to land-centric linguinstic insufficieny.3

But what of the scuba suit itself, that enabler of undersea experience? Can we fathom a framework for underwater fashion? For an aesthetics of depth? According to an ad for colour-coordinated dive accessories in a very Technicolor 1987 issue of Skin Diver Magazine, there is an old adage that ‘all divers look alike underwater,’ as ‘black neoprene clones of each other.’4 Neoprene, however, took centuries to arrive (first patented in the 1930s, it was only incorporated in wetsuits in the 1950s). Fish intestine and fish skin garments, natural rubber, waterproofed leather and oiled cotton were among its material precursors, and should therefore figure as peripheral agents in any prehistory of the scuba. (Interestingly, new sub aqua tech-wear developed at the Speedo Lab seeks to simulate the streamlined seamlessness of shark skin, making analog animal fabrics come full circle.)

What morphs into the scuba diving suit begins in a state of undress. It begins, simply, as the body, unaugmented. Multiple genres of diving — skin, free and scuba (shorthand for ‘self contained underwater breathing apparatus’) — complicate an easy lineage of designs that ensue, for most are hybrids of each, varying assemblages of mask, helmet, tank, tubes, wetsuit and fins. Skin and free diving find description as early as Greco-Roman times, where self-fashioned reed ‘snorkels’ were used in combat. Aristotle describes a basic diving bell used by Alexander the Great in fourth century B.C. waters. Fourteenth century Persian pearl divers used some of the earliest goggles, made from tortoiseshells. In the sixteenth century, Leonardo da Vinci became the first to diagram his scheme in his Codex Atlanticus for a diving suit equipped with a proto-scuba air tank, conceived for use in naval battles — a design so visionary as to not be fully realised until Cousteau and Gagnan’s iconic ‘aqua-lung’ innovation of 1943.

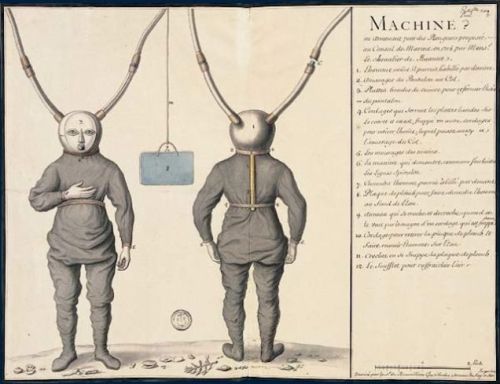

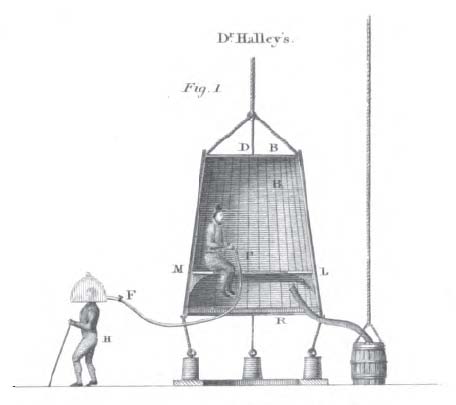

The first practicable diving suits were, in fact, more like chambers: underwater enclosures configured in cumbersome diving bell arrangements, which functioned as airtight containers for one or several divers. Divers would parasite a finite supply of air, a system still unequipped to self-replenish, while they were controlled by sailors at the surface. Astronomer Edmund Halley’s elaborate seventeenth century diving bell contraption accommodated several ‘assistants’ within one bell, so that another diver could exit and roam the seafloor (wearing the first known diving helmet, no less). Pierre Remy de Beauve’s diving dress (c. 1715), on the other hand, refined the bell scenario by fitting two hoses into a helmet attached to a waterproof suit. Antennae-like, one channelled air from the surface through a bellows, while the other conveyed exhaled air to the surface.

Not all early designs were as streamlined as de Beauve’s, and metal and wood substituted for the slickness of neoprene. John Lethbridge’s diving machine (also c. 1715) completely engulfed its diver’s body within an airtight oak barrel, save for two portholes for extending arms through in order to salvage valuables from wrecks — a design so architectonic as to serve as a veritable body house. In time, diving bells transmigrated into hard-hat diving dress, also known as standard diving dress, becoming less and less like space suits, and more and more like early body-con. The now quintessential diving ‘look’ in the form of the scuba diving suit, in both drysuit and wetsuit models, arrives in force in the mid-twentieth century, courtesy of the aqua-lung.

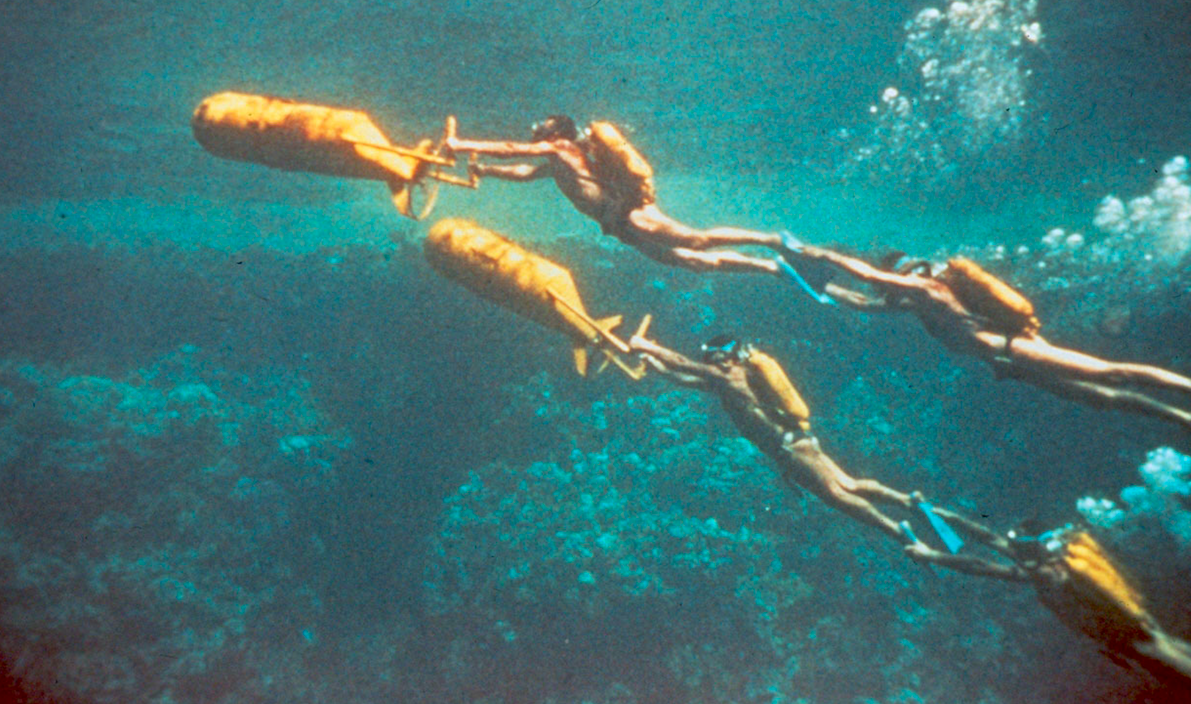

Captain Jacques-Yves Cousteau and Émile Gagnan’s invention, the aqua-lung was the first commercially manufactured automatic re-breather and portable deep-sea scuba diving technology to gain widespread traction. Released in 1943, it enabled divers to spend prolonged periods of time underwater at significantly lower depths — an experience encapsulated in Cousteau’s experiment in living in undersea villages on Conshelf I, II and III, which he and his crew of ‘oceanauts’ chronicled in A World Without Sun (1964).

It was for suturing the diver from the surface that the aqua-lung was most notable. Whereas before, an umbilical cord to ‘surface-supplied diving equipment’ (SSDE) was still required for oxygenation, such that divers were essentially underwater puppets rather than graceful free agents, the aqua-lung provided release and reason for becoming true ‘men-fish.’ As an enabler of free movement, the aqua-lung is to diving what Isadora Duncan is to modern dance, or Coco Chanel to the corset.

Rendered iconic in underwater cinematography, the aqua-lung pioneered what scholar Jon Crylen theorises as a ‘visual aesthetic of freedom from the surface’:5 now, streamlined and untethered, one could both look and behave like a fish. And indeed, it was in connection with his radical research on dolphin communication that neuroscientist John Lilly became fascinated by the aesthetics of suspended weightlessness proffered by the aqua-lung, the nearest analog of the dolphin’s own perceptual experience. According to D. Graham Burnett, Lilly annotated such lines in his copy of Cousteau’s The Silent World as ‘as we submerged, the water liberated us from weight.’6

In his 1947 book Breathing in Irrespirable Atmospheres and, in some cases, also Under Water, diving technologist Robert Davis unfolds the extent to which underwater diving dress evolved as a corollary of respiratory prosthetics developed in flying suits for high altitudes, as well as for use in gas masks. He draws out a lineage linked to ‘false mouths,’ closed-circuit breathing apparatuses camouflaged as masks, to treat respiratory ailments.7

Not dissimilarly, certain projects within the field of contemporary respiratory prosthetics alight from the potential for prosthetics to be dealt with as garments. In 2018, Jun Kamei, self-described as a biomimicry designer and material scientist, designed a 3D-printed ‘gill garment’ for our ‘aquatic future,’ while a Masters student at the Royal College of Art in London. Called the Amphibio, the garment, which conjures the intricate pleatings endemic to Issey Miyake and Iris Van Herpen’s designs, permits prolonged, although not yet unlimited, breathing underwater — not by producing oxygen, but by extracting it from sea water through porous printed interfaces. Still in prototype phase, the garment consists of a bone-coloured gill that tumbles like an out-folded Elizabethan ruff, serpentine as a python, down the chest, and a translucent respiratory mask connected by a tube. A far cry from body-occluding diving bells, this is an oxygen tank turned ornamental armour.

In its insistence on the ‘aquatic future,’ Kamei’s prototype ricochets interestingly with research conducted in the 1960s by Swedish scientist Per Scholander, which revealed amphibian dispositions in human physiology by proving that humans actually gain oxygen and experience decreased heart rates while diving — a phenomenon known as the ‘mammalian dive reflex.’ The research indicated that bodies by themselves, without wetsuits or added weights, are perfectly suited in buoyancy to that of water; that with breath modulation, one can walk on the seafloor as on land.8 If speculative futures of amphibious becomings — where the question of dressing for breath capability is key — are closer to lived realities than might be realised, then Kamei’s garment functions propositionally in pioneering a nascent genre of glamphibious fashion: one which is closer to mermaids of undress than to Cousteau’s frogman suit.

It may not be surprising that an offshoot category of contemporary wetsuit finds itself driven by the mythographic mermaid imaginary, an aesthetic evocative of undersea fem-punk. Here, the hashtag ‘tailmaker’ leads one deep into mermaid tail manufacture: for divers who wish to metamorphose into naiadic cliché, MerNation has manufactured silicone tails since 2012, while Otter Bay offers custom ‘full body mermaid wetsuits,’ equipped with a ‘split mono-fin.’ That most mermaid wetsuits still require oxygen tanks undermines Jon Crylen’s assertion that the ‘absence of diving technologies’ is ‘crucial to the mermaid image.’9 Look, for instance, at historic ‘aquabelle’ spectacles at Weeki Wachee Springs in Florida, where underwater dancers would sooner hold their breath for up to forty five seconds while performing stunts than wear oxygen cylinders.

Lore has it that Surrealist Andre Breton first sighted Jacqueline Lamba, his wife to be, as a nude underwater dancer swimming in a glass pool at the Coliseum on rue Rochechouart in Paris — a proto-van Herpen moment. When I met ninety-eight-year-old artist Luchita Hurtado at her recent opening at Hauser & Wirth in New York City, I asked her whether this anecdote had been recounted while she was in Breton or Lamba’s presence — for Luchita had mixed with a milieu in Mexico City that counted Breton, Lamba, Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo and Leonora Carrington as members. She remarked, ‘Well you knew that that’s what she [Lamba] was about, because she never wore a top to anything!’ If the climate wills it, catwalks of the future may be fin-fuelled, rather than legged.

Emma McCormick-Goodhart is an artist, writer and researcher based between New York and London.

‘NEEMO 5 Mission Draws Parallels Between Ocean Floor and Outer Space,’ NASA, www.nasa.gov/missions/earth/neemo5, June 25, 2003. ↩

Alice Morby, ‘Iris van Herpen explores the contrasts between water and air for Aeiform couture collection,’ Dezeen, www.dezeen.com/2017/07/05/iris-van-herpen-explores-contrasts-between-water-air-aeriform-couture-collection-design-fashion/, July 5, 2017. ↩

William Beebe, Beneath Tropic Seas: A Record of Diving Among the Coral Reefs of Haiti, New York, G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1928, p. 36 ↩

Bonnie J. Cardone, ‘Wenoka’s Color Coordinated Dive Accessories: Reflect Your Personality,’ Skin Diver, January 1987, p. 25 ↩

Jon Crylen, ‘Living in a World Without Sun: Jacques Cousteau, Homo aquaticus, and the Dream of Dwelling Undersea,’ JCMS: Journal of Cinema and Media Studies 58, No. 1, Fall 2018. ↩

D. Graham Burnett, The Sounding of the Whale: Science and Cetaceans in the Twentieth Century, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012, pp. 579 – 580. ↩

Robert H. Davis, Breathing in Irrespirable Atmospheres, and in some cases, also Under Water, London: St. Catherine Press, 1947. ↩

Robert H. Davis, Breathing in Irrespirable Atmospheres, and in some cases, also Under Water, London: St. Catherine Press, 1947. ↩

Jon Crylen, ‘Living in a World Without Sun: Jacques Cousteau, Homo aquaticus, and the Dream of Dwelling Undersea,’ JCMS: Journal of Cinema and Media Studies 58, No. 1, Fall 2018, p. 20. ↩