The most courageous act is still to think for yourself aloud.

Coco Chanel

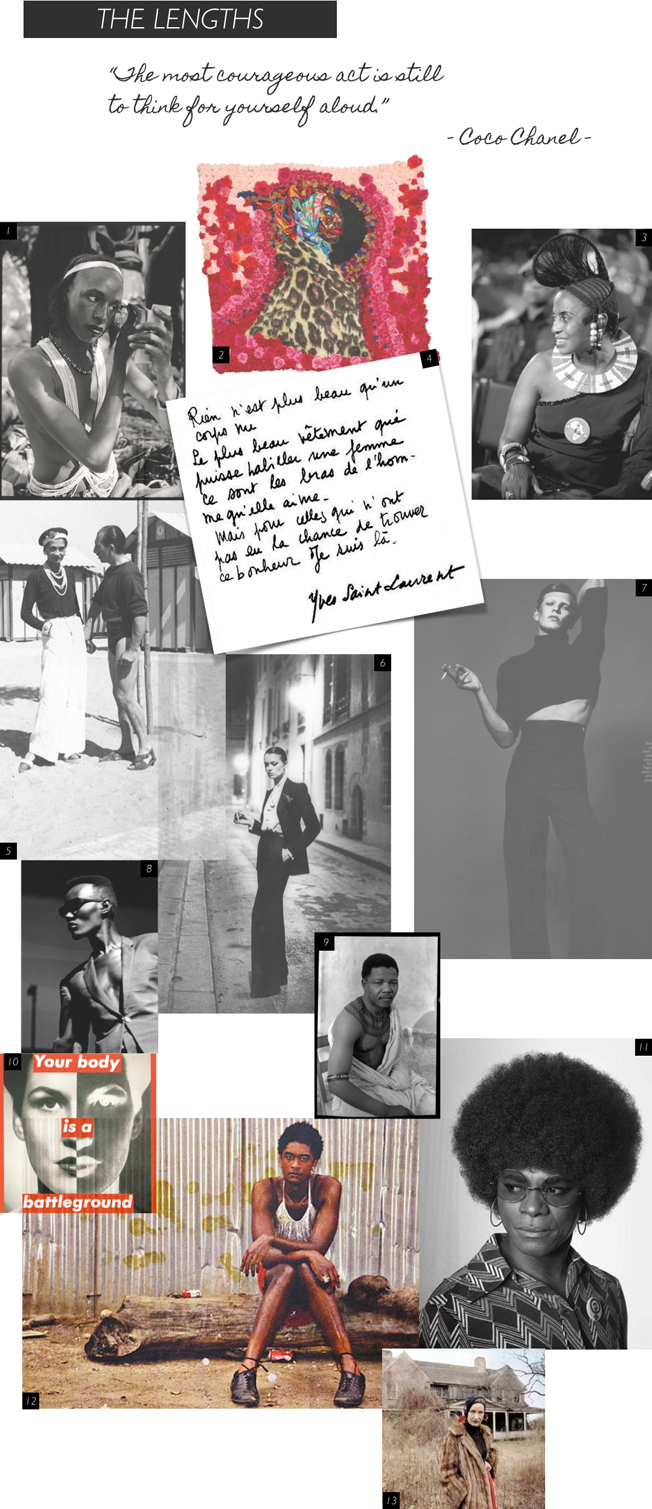

THE BODY IS A realm of political, social and cultural negotiation; and as such, dress and adornment powerfully represent characteristics within these categories. Artist Barbara Kruger summarises this function eloquently on her 1989 poster, ‘Your body is a battleground’. As the body is crucial to our whole understanding of dress and fashion, it is both vulnerable and powerful as it is symbolically manipulated with clothing. In the third instalment in the collaborative series between Vestoj and Another Africa, we explore the lengths we go to in building meaning onto the body.

When Nelson Mandela wore a bathrobe and neckpiece to represent the traditional costume of his Thembu tribe to his trial after evading authorities as the ‘Black Pimpernel’, he was communicating a distinct message with the body, one of resilience and protest in the wake of his political persecution. Similarly to Mandela the politically symbolic Miriam Makeba often wore her hair in the traditional Fulani style, a sartorial presentation that was inextricably linked to her political identity and context. Considering examples such as these, Coco Chanel’s words, ‘The most courageous act is still to think for yourself aloud’ might speak of the act of externalisation, and of the materialisation of ideas and intent on the body. The politics of the body are also at play when we look at the reappropriation of menswear for women, and notions of androgyny, from Marlene Dietrich’s seminal presentation in tuxedo trousers in the 1930 film ‘Morocco’ that influenced the iconic Helmut Newton image of Yves Saint Laurent’s ‘Le Smoking’, invoking the historical narrative of women wearing pants.

Notions of gender also come into play here: a realm in which the fluidity of dress becomes particularly powerful. In one image, a Woodabe man prepares for the Gerewol festival in Tahoua, Niger with extreme care; preening, dressing and applying make-up to impress members of the opposite sex in the ceremony, an age-old tradition of the region. In more contemporary phenomena, similar lengths might be taken by followers of high fashion, or the act of dressing to transgress gender.

Dressing the body is an act of covering nakedness – the fashioned figure’s opposition. In this sense, nakedness is a blank canvas, with no signifiers of social and cultural context, and from which the process of concealing (and sometimes revealing) occurs. In the words of Yves Saint Laurent, ‘Le plus beau vêtement qui puisse habiller une femme, ce sont les bras de l’homme qu’elle aime.’ or ‘The most beautiful clothes that can dress a woman are the arms of the man she loves.’ Suggesting that the purest expression of the body is one without fashion, and its symbolic trappings, this expression sits in contrast to Newton’s image of ‘Le Smoking’.

A decade earlier, the sexually emancipated image of Grace Jones whose presentation of power balances masculine and feminine aesthetics with commercial success, has some strong visual and symbolic parallels with YSL’s ‘Le Smoking’. To the right, Samuel Fosso’s black and white photograph ‘Angela Davis’, from the 2008 series ‘African Spirits’, is an image that is straightforwardly ambiguous. In the tradition of self-portraiture of photographers like Cindy Sherman, Fosso dressed himself as key African and Black American political figures and images for the series. The styling of the portrait of himself as the Black Panther figure, political activist, intellectual and feminist Angela Davis, engages with notions of ownership – of an image and one’s appearance, and its political and gender-based signifiers and historical narratives of resistance.

Across all of these images, each presenting varying manipulations of dress and its manifestation on the body with differing connotations; the notion of the body, the surface upon which identity is formed, still holds true. Through this process of presentation, the intent of an individual is externalised on the surface of the body; but also we are able to take ownership and claim our body through these lengths.

- Woodabe man of the Fulani ethnicity preparing for the Gerewol festival, Tahoua, Niger, photograph by Jean-Christophe Huet

- Athi-Patra Ruga, ‘UnoZuko’, 2013. Courtesy of Whatiftheworld Gallery, Cape Town, South Africa

- Miriam Makeba wearing a Fulani hairstyle c.1970s

- ‘Rien n’est plus beau qu’un corps nu. Le plus beau vêtement qui puisse habiller une femme, ce sont les bras de l’homme qu’elle aime. Mais pour celles qui n’ont pas eu la chance de trouver ce bonheur, je suis là.’ Yves Saint Laurent, 1983, translated as ‘Nothing is more beautiful than a naked body. The most beautiful clothes that can dress a woman are the arms of the man she loves. But for those who have not had the chance to find happiness, I am there.’

- Fashion designer Gabrielle Coco Chanel with Duke Laurino of Rome on the beach at the Lido, 1930, photographed by Gjon Mili

- ‘Le Smoking’ by Yves Saint Laurent, photograph by Helmut Newton for Vogue Paris in 1975.

- ‘Rive Gauche et Libre’ editorial for Vogue Paris, September 2010 featuring Josh Parkinson, photograph by Mert Alas & Marcus Piggot, with styling by Carine Roitfeld

- Grace Jones in her ‘One Man Show’ in 1982, photograph by Adrian Boot

- Nelson Mandela portrait wearing traditional beads and a bed spread, in hiding from authorities as the ‘black pimpernel’, 1961. Photograph by Eli Weinberg

- Barbara Kruger, ‘Untitled (Your body is a battleground)’, 1989

- Samuel Fosso, ‘Angela Davis’ from the series ‘African Spirits’, 2008

- Nástio Mosquito’s ‘Mulher Fósforo’, 2006. Courtesy of Sindika Dokolo Foundation

- Edith Bouvier Beale in ‘Grey Gardens’, 1975

Missla Libsekal is the founding editor of Another Africa.