On her left wrist, Katy Perry has a tattoo that says ‘Jesus’ in black cursive. On the cover of Rolling Stone in 2010, she appeared wearing powder-pink underwear and promising revelations about, yes, ‘Sex,’ but also ‘God.’ These were the only things one really needed to know in order to know about Katy Perry – all about her being the girl of easy virtue and pat, all-American innuendo, who had metaphorically given herself to Jesus, only to find that Jesus, being a messianic rat, had never called her back – until a few months ago, when Katy Perry underwent some kind of metamorphosis, beginning with her hair. It is strange how much a haircut means for somebody famous: Britney Spears, in shaving her hair, had martyred herself. She had unsexed herself like Joan of Arc. She was attempting to shear off, I guess, the gaze, and the fact of being Britney Spears.

(It worked, at least a little and at least for a short while; although like your mother tells you when you get a bad cut, it will always grow back. Britney’s Britney-Spears-ness grew back, but a little different. Sometimes that’s the case.)

This May, Katy Perry ended things with a tedious Hollywood actor that I don’t particularly care to name – and much like many of us, by which I mean many women, and like many of them, by which I mean particularly famous women, cut her hair. She cut it in a sort of boyish style, a gamine. Rather than her usual shade – ‘as pitch, as noir, as hate,’ as the critic Manohla Dargis said about the films of David Lynch; more on him later – it was bottle-blonde. ‘I feel free,’ she said on Snapchat, light and eager. She had certainly begun to act a little like a basement escapee. There was a curious stage performance of her single with the hip-hop trio Migos, where she danced like someone making fun of bad Caucasian dancing. There was a performance prank at the Whitney where she acted like a severed head on a dining table, and a sexually cannibalistic music video. She live-streamed her ‘life’ online for three full days, while speaking with a therapist, and playing a game of truth or dare in which the forfeit was to eat cow tongue, or a scorpion, or pickled pig’s feet; birds’ saliva, or a one-hundred-year-old egg. She rated her ex-boyfriends’ sexual stamina, and said that she would fuck them all quite happily as soon as nobody was watching her on YouTube any more.

David Lynch describes her these days as his ‘dear friend,’ which makes Lynch fans furious, maybe because they have not yet noticed Katy Perry acting more and more like, as the tagline says for Inland Empire, A Woman In Trouble: flailing, freaking out, behaving like a fantasist. (‘I think when you put sex and spirituality in the same bottle and shake it up, bad things happen,’ she once said, which is more or less a précis of the whole Lynch oeuvre.) Katy Perry is, quite suddenly, an interesting person. She is – in that strange performance, jerking and bizarre and utterly at odds with Migos in her nerdy paleness – like a parody or perfect specimen of the kind of paralysingly conservative, American-specific whiteness that obsesses the director. Onstage, Katy gurns like Laura Dern. She acts as though she does not know what stardom is, or sex appeal requires. She also has a split identity, and clearly finds this break-down between person and persona traumatising: on the live-stream, she is seen explaining to her therapist, in tears, that she had cut her hair – like Spears – in order to enact an exorcism. ‘I’m really strong as Katy Perry and then sometimes I’m not as strong as Katheryn Hudson,’ she said, referring to her birth name. ‘People, like, talk about my hair, right? They don’t like it or they wish that it was longer. I so badly want to be Katheryn Hudson that I don’t even want to look like Katy Perry anymore sometimes. That is a little bit of why I cut my hair, because I really want to be my authentic self one hundred percent. It hurts when I don’t feel like I can.’

Cutting off one’s hair and going blonde is not de facto necessarily a route to authenticity. For Marilyn, it meant an inauthentic means of obfuscation. Norma Jeane, her Katheryn Hudson, disappeared inside the white-blonde heat of Monroe. She became a gorgeous phantom. ‘My friend Nico, who lives in Pomona,’ says a homeless woman near the end of Inland Empire, ‘has a blonde wig. She wears it at [sic] Paris. But she’s on hard drugs and turning tricks now. She looks very good in her blonde wig, just like a movie star. Even girls fall in love with her when she’s looking so good in her blonde star wig.’ Marilyn’s blonde star wig was perpetual, a fixture. It allowed her to inhabit two worlds, real and unreal, present and then absent, and it brought her what she wanted or she needed, which was love – love even or especially from girls, who idolised her way of seamlessly embodying the fantasies of men.

What was difficult for Marilyn a little later – or for Norma Jeane, who lived inside the Marilyn persona – was her need to be regarded as a fully realised being (difficult, although it may not sound like much, for famous women). Her authentic self was not a pale erotic phantom after all, but a New York intellectual: a method actress, and the wife of a playwright, and a wearer of discreet and modest clothes, a poet and a diarist. What frightened her the most was thinking Norma Jeane might, over time, disintegrate, and that she might be left with only Marilyn: a hollowed outline in a woman’s shape, a white dress hanging empty like a shroud; a spooky horror-movie bed-sheet, two holes showing panicked eyes, an animal confusion. In her journal she writes:

Best finest surgeon – [acting coach Lee] Strasberg to cut me open which I don’t mind since Dr. H has prepared me – given me anaesthetic and has also diagnosed the case and agrees with what has to be done – an operation – to bring myself back to life and to cure me of this terrible disease whatever the hell it is – and there is absolutely nothing there – Strasberg is deeply disappointed but more even – academically amazed that he had made such a mistake. He thought there was going to be so much – more than he had ever dreamed possible… instead there was absolutely nothing – devoid of every human living feeling thing – the only thing that came out was so finely cut sawdust – like out of a raggedy ann doll – and the sawdust spills all over the floor & table and Dr. H is puzzled because suddenly she realises that this is a new type case. The patient… existing of complete emptiness.

This was 1955, when Marilyn had every reason to believe herself a worthy vessel for the love and admiration of the public, and had nevertheless convinced herself that she was worth- less, fraudulent, and empty. She began to go to acting classes in no make-up, wearing headscarves. She would speak so hesitantly that her classmates claimed they barely heard her. She wore black and dreamed of looking dowdy, i.e. clever – which was not, I need not mention, what the public wanted. It was never how they dreamt her when they dreamt her, which was often: as a star, she said, ‘you’re always running into everyone’s unconscious,’ and by this time she had done her share of running. It was not surprising that she felt fatigued; nor that the corridors she occupied inside the minds of men, like labyrinthine psychic movie sets, began to feel oppressive.

‘I’ll never forget the day Marilyn and I were walking around New York City, just having a stroll on a nice day,’ Amy Greene, the wife of Marilyn’s photographer and lover Milton Greene, and one of Marilyn’s few female friends, once said. ‘She loved New York because no one bothered her there like they did in Hollywood, she could put on her Plain Jane clothes and no one would notice her. So as we’re walking down Broadway, she turns to me and says “Do you want to see me be her?” I didn’t know what she meant but I just said “Yes” – and then I saw it. I don’t know how to explain what she did because it was so very subtle, but she turned something on within herself that was almost like magic. And suddenly cars were slowing and people were turning their heads and stopping to stare. They were recognising that this was Marilyn Monroe as if she pulled off a mask or something, even though a second ago nobody noticed her. I had never seen anything like it before.’

A subtler split in self had taken place in Norma-Marilyn than simply putting on or taking off a blonde star’s wig, so that the Marilyn persona had begun to be called only ‘Her,’ and Norma Jeane began to hide behind ‘Her’ for the sake of going silently, unseen. ‘She’ did not, outside Hollywood or Photoplay, exist. ‘Her’ lovers grasped at nothing. Joe DiMaggio was terrified of ‘Her,’ and wanted only her; Arthur Miller thought that ‘She’ would make an ideal muse, but had not guessed that she herself – the real, authentic she – would have tough thoughts, an inner life.

This lover-centric schizophrenia sounds a lot like fame. It’s also, in some voyeur-peeped and subsequently itchy way, the very thing of being female, though it might be best defined as ‘femininity’ specifically – the spectacle of femininity as falsehood, an illusion, something by design. Marilyn embodied femininity so femme it might as well be drag, which made Jayne Mansfield’s even-draggier impersonation of her feel recursive. Somehow broader, naked-er and even more like sex personified than Marilyn, Mansfield had the added complication of being a certified genius, and a member of MENSA. As seen ably playing violin in 1957 on The Ed Sullivan Show, she reveals herself to be far more than just a sex comedienne, and far less of a bimbo than the average viewer might have guessed, and just about as far from how we picture those with genius IQs as it is possible to get. She glows, a statuette.

She does not play a second of the thing for laughs. The footage is astounding for, above all else, the knockout violinist’s real sincerity. I almost cried observing the straight, grim mouth, the furrowed brows; the lowered lashes, like a pair of blackout curtains. (Mansfield plays the violin, the audience is thinking, like an ugly girl.) ‘Jayne Mansfield, who was not a dumb blonde, spent most of her adult life in the service of that image,’ Roger Ebert wrote in 1967, when the actress crashed her car and died, at thirty-six. ‘She was so successful that today, as she lies dead in New Orleans, there is very little to say about her that is not the invention of a press agent… Everyone knew that Mansfield’s measurements were 40-22-35, but not many in her audiences knew very much more than that. She didn’t want them to.’

Born in Bryn Mawr Pennsyvania, and really named, ignobly, Vera Palmer, she had always said that her attraction to her husband Mickey Hargitay had stemmed from knowing that they looked like two cartoons: a big-M Man, and a big-G, double-D Girl. This does suggest that Jayne believed, like most good auteurs and good engineers of image, in employing symbolism over literalism. In Blue Velvet – Lynch’s masterpiece from 1986, and as good a criticism of the compensatory-high-macho U.S. male as ever put on film – the characters are split into, if not exactly good and evil, innocence and kink. That blondes are usually the good girls and brunettes the bad did not apply in Mansfield’s universe, but does here: nightclub singer Dorothy performs Blue Velvet in a manner that suggests narcotics or near-orgasm.

Her black hair and bare back and European intonation all spell trouble – which they should, as Dorothy is mad with grief, and mad for sexual kicks. She makes the song Blue Velvet into porno, just like Mansfield makes the violin a shock. One more singer who has made the Bobby Vinton hit into a sexual fantasia, and a mind-fuck, is the none-more-heavy- of-persona singer and femme icon Lana Del Rey, whose false lashes are less blackout curtains than they are lead shutters – whose blonde hair became yet more brunette, a little more like pitch, like noir, like hate, with every passing album. ‘When I went darker with my hair,’ she told a journalist at Maxim, ‘I don’t know why, but people took my music more seriously.’

Mansfield might know. Hiding in persona, for a woman who is smart, is almost easiest assuming this persona’s hair is blonde. It does the work. The work is not exactly stimulating, but is sometimes useful. The idea in general is that bright, pale blondeness signifies a disconnection from the intellect: a stoned vacation into something Less Than in the head. The same might just as easily be said about injected lips, or mink-fur lashes, or the smeared and heavy finger-painted smoky eye that Lana has adopted for the last six, maybe seven years. It might be cat-eye make-up – but no cat would ever be so clumsy. No cat ever lets itself look quite as touched, as ruffled, as Del Rey has in her early shoots, or on the beach in paparazzi shots, or at her concerts. Just like Dorothy, she makes a good deal out of bad men.

‘I’m not who you think I am,’ the characters in Inland Empire often say, both male and female, when they are possessed by something either literally or metaphorically. ‘Are you listening to me?’ Coming out with ‘Video Games’ in 2011, Del Rey – whose name is really Lizzie Grant; whose daddy is a millionaire – might not have figured that the industry would be so brutal to a phoney who was only being phoney for the sake of glamour. She had never tried to hide the fact that she was not the girl we thought she was, although this never stopped male critics trying to unmask her. ‘This,’ they all said, stonily and brandishing her picture like a weapon, ‘is the girl.’

I am not certain why they bothered. She was being ‘Her,’ but also just as happy to be her; and anyway, the mask did not pretend to be a natural human face. It did not try to say much other than ‘fuck me’ or ‘fuck you,’ per its wearer’s mood. ‘The only real option [for Lana] is to wash off that face paint, muss up that hair and try again,’ said Jon Caramanica of The New York Times. Except: wasn’t this what Marilyn tried? They did not listen. Norma Jeane, if she had gone brunette, might yet have lived.

Philippa Snow is a writer based in Norwich, England.

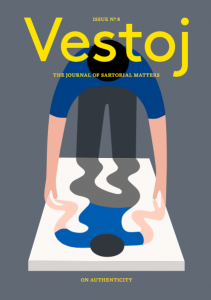

This article was originally published in Vestoj: On Authenticity, available for purchase here.