THE PERSONA OF THE architect first emerged in the Renaissance, when the discipline forcibly elevated itself above the building trades, professionalising what was previously a vocational pursuit. This schism created the need for a distinct professional identity, as, like doctors and priests, architects now required a uniform. Michelangelo was arguably the first to mold the discipline’s sartorial culture with his all black clothing that was immortalised in Domenico Cresti’s Michelangelo Presenting the Model for the Completion of St Peters to Pope Pius IV from 1619. Michelangelo’s black vestments could be said to embody the newfound anxieties of the profession, in which architects needed to identify themselves in order to attract commissions that, once won, defined the architect — no matter his own external status or personal success — as someone subservient to a client. Michelangelo’s clothes were therefore self-consciously considered relative to his patron, Pope Pius IV, with the quasi-clerical of the black robes simultaneously projecting blankness, severity, eccentricity, and humility. Some four hundred years later, the most famous contemporary architect, Frank Gehry, takes a similar approach when presenting his model of the Facebook headquarters to Mark Zuckerberg, wearing a black version of Zuckerberg’s own uniform of a plain T-shirt.1

The all-black clothing of the architect is now ubiquitous within the discipline, and its diverse associations with other social groups such as punks, beatniks and monks are all useful in cultivating the architect’s mystique. Yet despite these varied associations, the presence of a singular disciplinary uniform is unique among creative types. Artists have a far greater diversity of personas — Hockney’s irreverent prep, Basquiat’s dressed down Armani — while the paucity of architects dressing outside the dominant mode highlights the profession’s curious and self-conscious tendency towards similarity.2 Despite this uniformity, architects are tellingly sensitive about their shared preference, with contemporary figures like Rem Koolhaas (falsely) claiming ‘I never wear black!’ and the young architect Andrew Kovacs cutting a discussion of fashion short during a 2016 Columbia GSAPP lecture by saying that ‘forced to comment on fashion, I will say that I prefer uniforms.’3 This refusal to acknowledge the architect’s sartorial persona exposes an anxiety that is central to the field, with architects simultaneously exerting high levels of control over their own clothing and anxiously suppressing any critical discussion of it.

No other figure is a better exemplar of this tendency than Le Corbusier, who actively constructed his public persona through fashion and dress, being one of the first public figures to instrumentalise his clothing through its representation in mass media. His highly engineered appearance still affects perceptions of the profession today, and to many, the architect is still a white man in a black suit, black turtleneck, and circular glasses. Le Corbusier’s anxious control over his clothing is manifest in the curious history of the garment he designed for himself in 1947 — the Forestière (French for forest) — a jacket meant to assist him in drawing. As the only item of clothing the iconic modern architect designed for his own use, the Forestière should be a canonical garment, central to Le Corbusier’s legacy and persona, yet it is little known either within architectural circles or outside, and there is no substantive reference to or documentation of its existence within literature native to the discipline or even within the archive of Le Corbusier himself. The Forestière’s fringe history of suppression and reproduction provides an object lesson in the power of clothing, both in its material presence, and in its intentional obscurity.

Le Corbusier began the design of the Forestière by basing the body of the garment on the gamekeeper’s jacket worn by Gaston Modot in the celebrated 1939 French film La Règle du Jeu, or, The Rules of The Game.4 The sleeves of the Forestière were modeled after those of a kimono, with a wide consistent width from armhole to cuff allowing for unrestricted movement.5 This Frankensteinian design strategy of sewing together mismatched arms and bodies allowed the garment to overcome the particular shortcomings of the original gamekeeper’s jacket and of all menswear tailored in the French tradition, whose tapered sleeves and structured shoulders are ideal for cutting a heroic figure but not well suited to the dexterous labour of drawing. The Forestière’s shoulders were designed to be unlined and unstructured, with the sleeve heads pivoted at a specific angle based on Le Corbusier’s position while working and drawing at his desk, structurally reinforcing the jackets definition as a tool. Le Corbusier subscribed to the architect’s penchant for black clothing and had the jacket made up in a colourway fit for a raven: black wide-wale corduroy with black silk lining.

Arnys, the Parisian boutique that Le Corbusier commissioned to construct the Jacket, introduced the Forestière into their ready-to-wear line in the 1950s and the jacket immediately became synonymous with the brand. These commercial reproductions were quite different from the original commission as the black corduroy was substituted for linens, cashmeres, and leathers in all the colours of the rainbow.6 In the 1990s, there were more structural changes, as Jean Grimbert, son of Arnys’ founder Leon Grimbert, modified the Forestière into its now recognisable Nehru style that more closely resembles the jackets worn by James Bond villains such as Dr. No than the gamekeeper’s jacket that was its original inspiration.7 The jacket worn by the nefarious architect Anthony Royal in the 2015 cinematisation of JG Ballard’s High Rise is said to be based off this version of the Forestière — marking the garment’s re-imagining on the silver screen after its initial inspiration in The Rules of The Game. Given this long and surely incomplete history of changes and reproductions, the exact details of the original seem impossible to pin down, and while a photograph of Le Corbusier wearing the Forestière would be useful in sorting out these differences, none exist. This absence is most apparent when such photographs can’t be found in Arnys’ own advertisements. Arnys built itself into an institution that counted the likes of Yves Saint Laurent, Jean-Paul Sartre and François Mitterrand among its loyal clientele by crafting its brand identity around Le Corbusier and the Forestière’s mystique.8 Given the effort put into linking Arnys, Le Corbusier and the Forestière, one can be reasonably sure that if any such image existed, it would be used in those, or some other, Arnys advertisement.

The likely reason for the absence of any photographic documentation of the original Forestière is Le Corbusier’s active curation of his own archive, the Paris based Foundation Le Corbusier founded in 1960, which allowed him preternatural control over his legacy. The architect himself preserved, assembled, and edited the archive’s collection in order to extend his control over his public image past his natural life. He is reported to have ‘obsessively preserved every letter, drawing, and photograph for posterity.’9 The absence of photographic documentation of a garment he commonly wore is therefore undoubtedly the direct result of Le Corbusier suppressing images that he felt would undermine his idealised persona — that of an aloof intellectual unburdened by the demanding labours of his profession. While the lack of photographs from the archive is telling, so too is the absence of the garment itself. Instead, the only sartorial objects Le Corbusier deemed worthy of preservation are now housed within in a category titled ‘glasses and ocular instruments Z1-10,’ a redundant collection of the many pairs of identical, iconic glasses he owned. Le Corbusier thus tellingly elevated the discrimination of his eye above the labours of his hand, whose movement the Forestière was commissioned to better facilitate, betraying an aversion to exposing both his act of working as well as the technical garments he worked in. This is symptomatic of the way Le Corbusier represented his process of drawing, famously disingenuously simulating the act during a CIAM meeting by briskly tracing over lightly projected drawings he had prepared beforehand in order to appear like an effortless savant — all while wearing the very sort of restrictive suit that inspired the Forestière in the first place.10

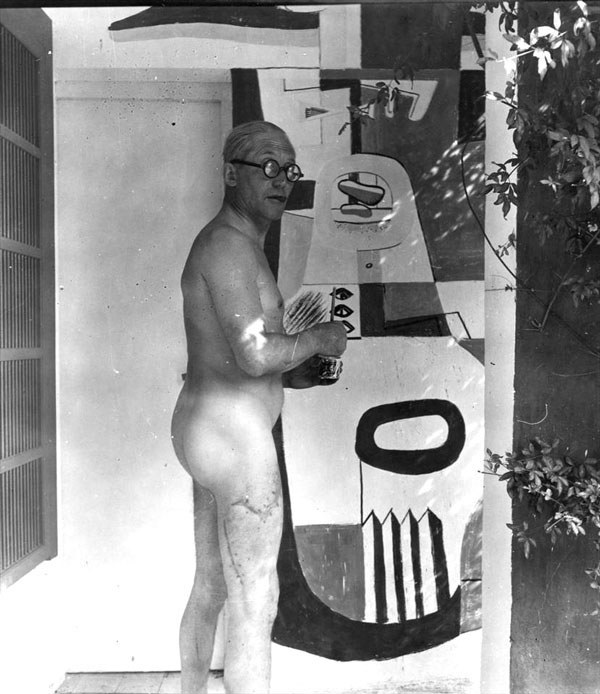

Le Corbusier clearly had anxieties around representing his working process and carefully considered what clothes to wear for work (the Forestière), what clothes to wear for public presentation (dark suits), and which of his sartorial trappings would represent him in his archive after his death (his eyeglasses). His anxious suppression of the Forestière goes back to the fundamental nature of the profession as a client-patron system, wherein the labour of architecture is often perceived by clients as a feat of savant-ism, a kind of immaculate conception of cerebral energies effortlessly manifested into a set of drawings. It is therefore no wonder the Le Corbusier suppressed the Forestière as a signifier of that labour and instead privileged images like the one of himself nude painting E1027, a representation of labour where he is not actually ‘at work’ as the mural is already finished and none of the disorder of his creative process is on display — as if, like Athena springing forth from a gash in Zeus’ head, the mural was born complete, straight from the mind of its father.11 Representations like the E1027 photograph serve to obscure the more imperfect and human act that his process of working actually was, requiring the strong seams, loose sleeves, and tough corduroy fabric of the Forestière.

The fringe legacy of the Forestière as a garment designed by an architect lives on in contemporary projects like Zaha Hadid’s 3D-printed heels and Liz Diller, Herzog de Meuron and OMA’s designs for the Spring/Summer 2019 Prada collection. While these garments are designed for others, they betray similar anxieties in their designers. As architects increasingly court celebrity, ‘starchitects’ like Rem Koolhaas, Frank Gehry, and Liz Diller confront the sartorial baggage associated with public personas in much the same way that Le Corbusier did sixty years prior. By participating in fashion as designers, they can forgo critical discussions of their own clothing, offloading expectations and pressures which might otherwise be reserved for the public presentation of their own bodies onto the bodies of the models they dress. Throughout all of this, the Forestière lurks as an obscure yet manifest presence, a kind of phantom of architectural culture whose spectral figure betrays the universal, disciplinary fears that are bound up in its history of intentional suppression.

Ian Erickson studies architecture at UC Berkeley.

Frank Gehry presenting a model of the Facebook headquarters to Mark Zuckerberg. The Guardian, March 10, 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/mar/10/facebook-zee-town-mark-zuckerberg. ↩

Cornelia Rau, Why Do Architects Wear Black? Wien, Springer, 2009. ↩

GSAPP, Columbia. ‘Laurel Consuelo Broughton and Andrew Kovacs.’ YouTube. October 20, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1E1u1gqcJQI. ↩

Craig Bassam, ‘La Forestiere: The Corbusier Jacket.’ BassamFellows Journal. http://bassamfellows.com/entry.html?id=95. ↩

Ville Raivo, ‘Arnys Forestiere,’ Keikari. http://www.keikari.com/english/arnys-forestiere/. ↩

Voxsartoria, ‘The History of the Forestière (according to Its Current Steward, Berluti).’ Voxsartoria, March 21, 2014. ↩

This is not another case of ‘East-meets-West’ however — as in the kimono and the gamekeepers jacket’s union in the original Forestière — but rather, the Dr. No jacket which is commonly associated with the Indian Achkan was actually more closely based off the WW1 German Gas Officer’s uniforms designed by Fritz Haber. Dunikowska and Turko, ‘Fritz Haber,’ 10057. ↩

Nick Foulkes, ‘Isn’t It Iconic…’ How To Spend It. October 13, 2013. https://howtospendit.ft.com/mens-style/37743-isnt-it-iconic. ↩

William JR. Curtis, ‘Le Corbusier: Ideas and Forms.’ ArchDaily, April 10, 2015. https://www.archdaily.com/617466/le-corbusier-ideas-and-forms. ↩

Malcolm Millais, Le Corbusier: The Dishonest Architect. Newcastle upon Tyne, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2017. ↩

This photograph has its own complex and gendered history, see: Beatriz Colomina (1996) Battle lines: E.1027, Renaissance and Modern Studies, 39:1, pp. 95-105, DOI: 10.1080/14735789609366597 ↩