AS FAR AS I know, I was the first person to study the image of women in advertising. I started collecting ads in the late 1960s, tearing them out of magazines and putting them on my refrigerator with magnets. Gradually I began to see a pattern in the ads and to see certain themes emerging – such as the tyranny of the ideal image of beauty, the dismemberment and objectification of the female body, the obsession with thinness, and the normalisation of sexual assault and battering. I put together a slide presentation and began speaking about these issues throughout the United States. I made the first version of my film ‘Killing Us Softly: Advertising’s Image of Women’ in 1979 (and have remade it three times since then). Since then, advertising has become more sophisticated, more ubiquitous, and more powerful than ever before. Yet most people still believe that they are not influenced by it. Wherever I go, what I hear more than anything else is ‘I don’t pay attention to ads. I just tune them out. They hav no effect on me.’ Of course, I hear this most often from people wearing Gap T-shirts or carrying Louis Vuitton bags. The influence of advertising is quick, cumulative, and mostly subconscious. As the editor-in-chief of Advertising Age, the major publication of the American advertising industry, once said, ‘Only eight percent of an ad’s message is received by the conscious mind. The rest is worked and re-worked deep within the recesses of the brain.’ So we process these images over and over again, mostly subconsciously.

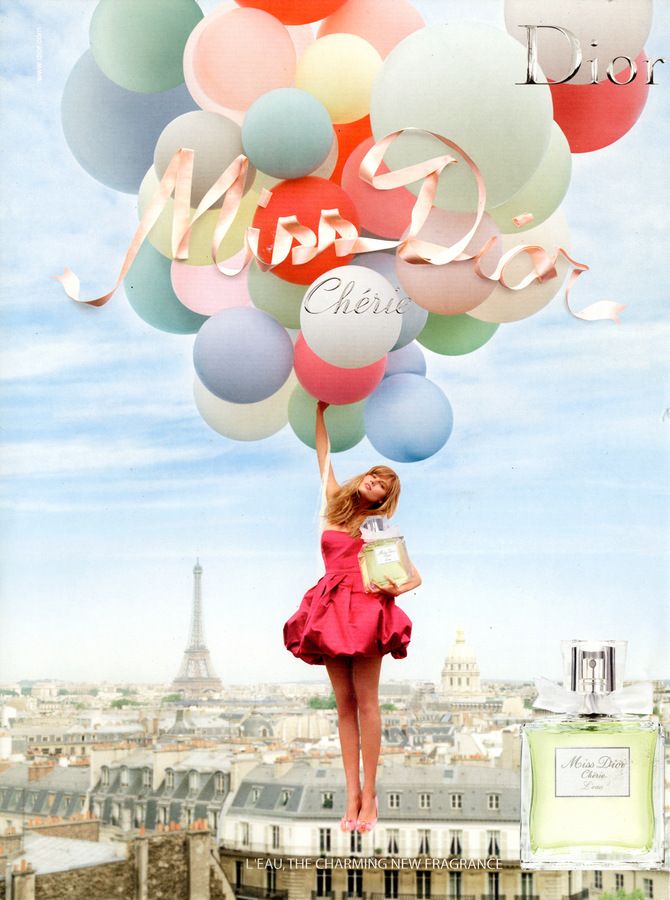

Ads sell more than products of course. They sell values, images, concepts of love and sexuality, of romance and success – and perhaps most importantly, of normalcy. To a great extent advertising tells us who we are and who we should be. One of the earliest and most disturbing themes I noticed was the sexualisation of little girls. From the beginning I felt that both the sexualisation of girls and the obsession with thinness were a kind of response to the growing feminist movement. Many people feel a lot of discomfort, even terror, at the thought of women becoming too big and too powerful. This terror is mostly subconscious and is experienced by many women as well as by men. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that, as women seized more opportunities and went into the work force and into medical schools, law schools and business schools, the ideal woman in advertising and popular culture became extremely thin. I’m not implying that this was a conscious conspiracy. Rather I think it reflects what the psychoanalyst Carl Jung referred to as ‘the collective unconscious.’

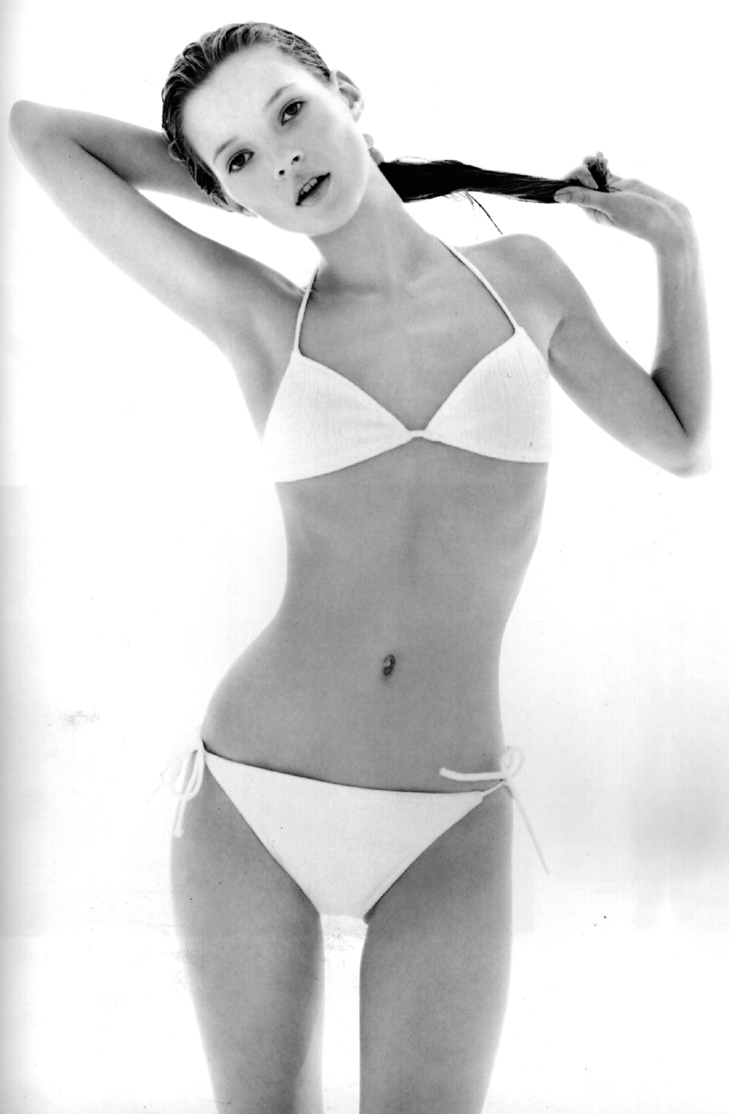

On the deepest level, the obsession with thinness is about cutting women down to size. This can be done quite literally now with Photoshop, as in the notorious Ralph Lauren ad from 2009 picturing an extremely whittled-down version of the model Filippa Hamilton. I remember seeing an ad for Armani Exchange featuring a very thin Asian woman with the tagline ‘The more you subtract, the more you add’. Of course, this is referring to simplicity in fashion but it implies more than that. At the same time as models were becoming thinner and thinner, advertising and pop culture began offering highly sexualised images of young girls, almost as if they were replacements for newly empowered women. As women moved away from the so-called ‘feminine’ traits of passivity, powerlessness, and submissiveness, images of sexy little girls proliferated. This sexualisation is not harmless. In 2007 the American Psychological Association published a report concluding that girls exposed to sexualised images from a young age are more prone to three of the most common mental health problems for girls and women: depression, eating disorders, and low self-esteem.

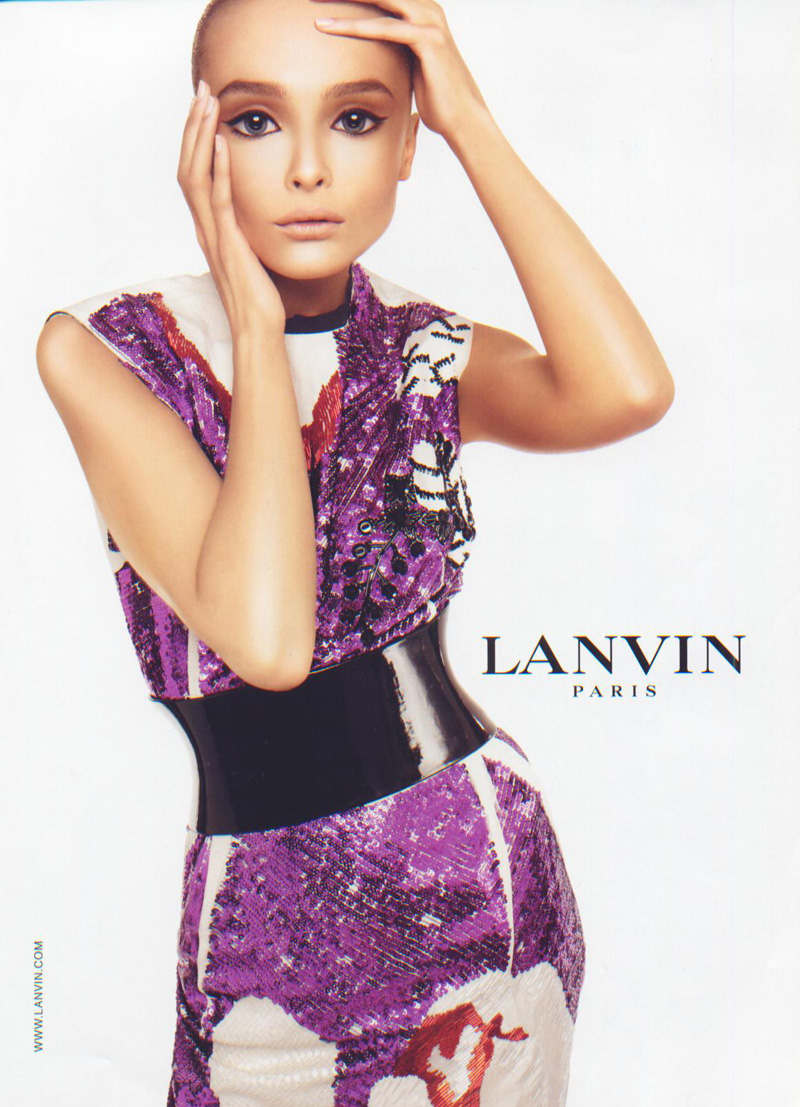

The flip side of this sexualisation of girls is the infantilisation of adult women. Signs of maturity in women – wrinkles, laugh lines, body hair – have never been acceptable in advertising or in popular culture in general. Women have long been expected to shave their legs and underarms, or face disgust if they don’t. Today women and girls are also exhorted to remove all or almost all of their pubic hair. We get the message that women are acceptable only if they are young, very thin, white (or at least light-skinned), perfectly groomed and polished, plucked and shaved. Any deviation from this ideal is met with contempt and hostility – which, of course, is waiting for all of us as we age. This repudiation of signs of sexual maturity in women is disturbing, to say the least, and has a powerful impact on female self-esteem.

Women are infantilised in advertising, especially in fashion advertising, in several ways. Sometimes the woman is dressed as a child or holds a childish prop such as a lollipop or teddy bear. Often the models pose in silly and childlike ways and sometimes the models are portrayed as having disproportionately large heads and eyes, telltale hallmarks of children. I have seen more grown women that I care to recall pose with their fingers in their mouths, or being symbolically silenced by having their hands over their mouths or their mouths covered in other ways.

In short, my point is that fashion advertising often sells more than fashion. My hope is that enlightened people in the industry will be more careful about what else they are selling, about the messages they are perhaps unwittingly conveying to girls and women (and boys and men too). We all are affected by these messages and we all have a profound stake in challenging them. As sociologist Erving Goffman, referring to the study of advertisements, said, ‘We must make what is invisible, visible, so we have a choice to make about how we want to participate in the world we inhabit.’

Jean Kilbourne is an American author and filmmaker who critically examines images of advertising.

This article was originally published in Vestoj‘s fourth issue, On Fashion and Power.