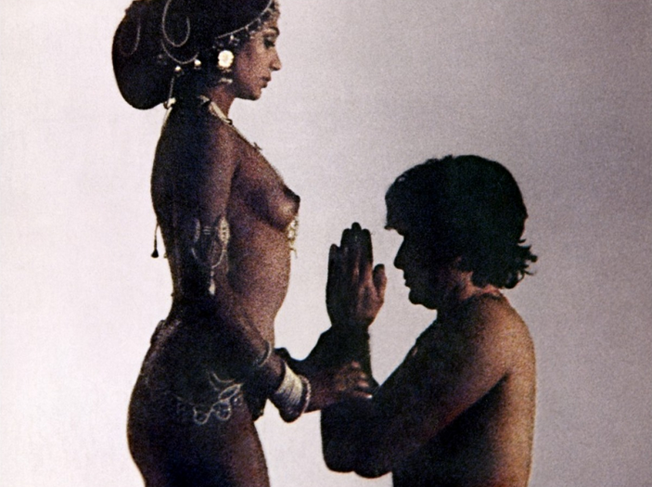

WRITTEN IN 1922, AND later translated to English in 1951, Siddhartha is a seminal work by the German author Hermann Hesse. The cultural influence of Siddhartha reached its apex in the context of the Sixties, in the burgeoning hippy era of the time, but the book has lasting resonance as a point of reference of early contact for the West with the alternative philosophies and narratives that became increasingly popular to experiment and explore with. The book is a spiritual journey which traces the main character Siddhartha, and his Indian pilgrimage to Buddha alongside his companion Govinda, denouncing the materialistic trappings of ‘perfumed hair’ and expensive clothes in the process of enlightenment. It is a work of its time, but it has become a figurehead of these, now mainstream, typically Eastern philosophies. The following passage served as inspiration for Raf Simons’ 2004 collection, but also, for a fashion reader, resonates strongly: here Hesse dismantles his fashioned appearance, in place of spiritual alternatives; the three ‘arts’ of ‘fasting, waiting, and thinking’.

***

“I know you, Govinda, from your father’s house and from the Brahmins’ school, and from the sacrifices, and from our sojourn with the Samanas and from that hour in the grove of Jetavana when you swore allegiance to the Illustrious One.”

“You are Siddhartha,” cried Govinda aloud. “Now I recognise you and do not understand why I did not recognise you immediately. Greetings, Siddhartha, it gives me great pleasure to see you again.”

“I am so pleased to see you again. You have watched over me during my sleep. I thanks you once again, although I needed no guard. Where are you going, my friend?”

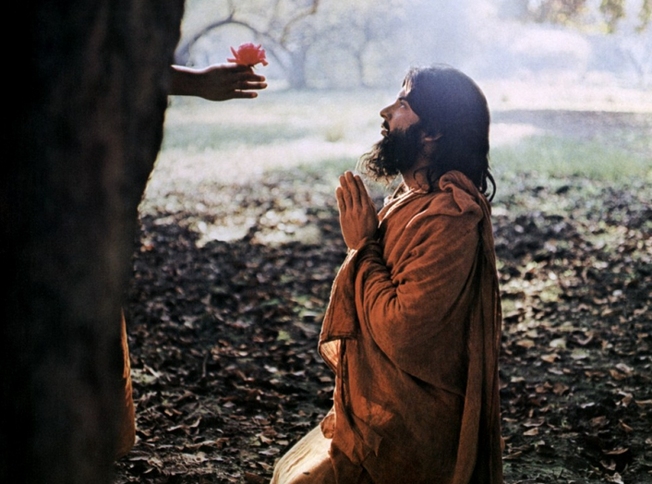

“I am not going anywhere. We monks are always on the way, except during the rainy season. We always move from place to place, live according to the rule, preach the gospel, collect alms, and then move on. It is always the same. But where are you going Siddhartha?”

Siddhartha said: “It is the same with me as it is with you, my friend. I am not going anywhere. I am only on the way. I am making a pilgrimage.”

Govinda said: “You say you are making a pilgrimage and I believe you. But forgive me, Siddhartha, you do not look like a pilgrim. You are wearing clothes of a rich man, you are wearing the shoes of a man of fashion, and your perfumed hair is not the hair of a pilgrim, it is not the hair of a Samana.”

“You have observed well, my friend’ you see everything with your sharp eyes. But I did not tell you that I am a Samana. I said I was making a pilgrimage and that is true.”

“You are making a pilgrimage,” said Govinda, “but few make a pilgrimage in such clothes, in such shoes and with such hair. I, who have been wandering for many years, have never seen such a pilgrim.”

“I believe you, Govinda. But today you have met such a pilgrim in such shoes and dress. Remember, my dear Govinda, the world of appearances is transitory, the style of our clothes and hair is extremely transitory. Our hair and our bodies are themselves transitory. You have observed correctly. I am wearing the clothes of a rich man. I am wearing them because I have been a rich man, and I am wearing my hair like men of the world and fashion because I have been one of them.”

“And what are you now, Siddhartha?”

“I do not know; I know as little as you. I am on the way. I was a rich man, but I am no longer and what I will be tomorrow I do not know.”

“Have you lost your riches?”

“I have lost them, or they have lost me. They have escaped my possession. The wheel of appearances revolves quickly, Govinda. Where is Siddhartha the Brahmin, where is Siddhartha the Samana, where is Siddhartha the rich man? The transitory soon changes Govinda. You know that.”

For a long time Govinda looked doubtfully at the friend of his youth. The he bowed to him, as one does to a man of rank, and went on his way.

Smiling, Siddhartha watched him go. He still loved him, this faithful anxious friend. And at that moment, in that splendid hour, after his wonderful sleep, permeated with Om, how could he help but love someone and something. That was just the magic that had happened to him during his sleep and the Om in him–he loved everything, he was full of joyous love toward everything that he saw. And it seemed to him that was just why he was previously so ill–because he could love nothing and nobody.

With a smile Siddhartha watched the departing monk. His sleep had strengthened him, but he suffered great hunger for he had not eaten for two days, and the time was long past when he could ward off hunger. Troubled, yet also with laughter, he recalled that time. He remembered that at that time he had boasted of three things to Kamala, three noble and invincible arts: fasting, waiting, and thinking. These were his possessions, his power and strength, his firm staff. He had kerned these three arts and nothing else during the diligent, assiduous years of his youth. Now he had lost them, he possessed none of them any more, neither fasting, nor waiting, nor thinking. He had exchanged them for the most wretched things, for the transitory, for the pleasures of the senses, for high living and riches. He had gone along a strange path. And now, it seemed that he had indeed become an ordinary person.

Siddhartha reflected on his state. He found it difficult to think; he really had no desire to, but he forced himself.

Now, he thought, that all these transitory things have slipped away from me again, I stand once more beneath the sun, as I once stood as a small child. Nothing is mine, I know nothing, I possess nothing, I have learned nothing. How strange it is! Now, when I am no longer young, when my hair is fast growing gray, when strength begins to diminish, now I am beginning again like a child. He had to smile again. Yes his destiny was strange! He was going backwards, and now he again stood empty and naked and ignorant in the world. But he did not grieve about it; no, he even felt a great desire to laugh, to laugh at himself, to laugh at this strange foolish world.

Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha was published in 1922 in Germany.