The seventh issue of Vestoj, ‘On Masculinities,’ will be in stores this month. In introduction, Vestoj Online is publishing a series of articles on the theme.

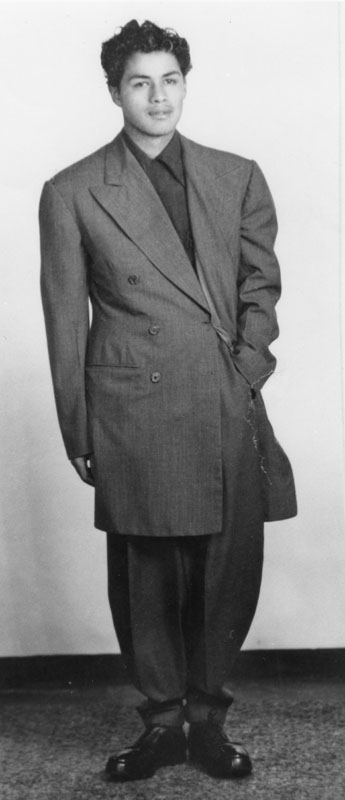

THE ZOOT SUIT WAS an icon of its time, born from the bespoke draped silhouettes of London’s Savile Row in the mid-1930s then adopted and exaggerated by young jazz-obsessed men and women across America. Amid a period of social and political turbulence just before World War II, the style was not only a means of dandyism, but also a badge of cultural identity for many African American and first-generation immigrant youths. Its exaggerated shape and distinctive details are familiar to many by way of classic images of performers Cab Calloway, Tin Tan and other jazz greats, as well as from the numerous tributes that have since been made to the zoot suit and its original wearers, such as Luis Valdez’s play Zoot Suit from 1978 and popular songs from L. Wolfe Gilbert and Bob O’Brien’s 1942, ‘Zoot suit for my Sunday Gal,’ to Cherry Poppin’ Daddies’ 1997 big band revival hit, ‘Zoot Suit Riot.’

Beyond our pop cultural knowledge of the zoot suit are numerous scholarly articles on the subject. Strong social, political, cultural and dress research have enumerated the significance of the zoot suit against its cultural backdrop of racial tensions during the interwar years. And indeed, the so-called ‘zoot suit riots’ of 1943 were a cultural obsession that headlined newspapers across the country, and masked what was essentially race warfare between whites and Chicanos and blacks with the military dress of servicemen and unpatriotic dress of zoot-suiters.

Yet for all of this breadth and depth of information and various descriptions of this extraordinary suit style, research on an existing example is scarce because so few have survived. Reasons for this vary. As zoot suits required much more fabric to create than a typical suit, its rarity may be partly due to WWII-era restrictions imposed by the War Production Board in March of 1942 to reduce the amount of fabric used in garment construction, effectively limiting the production. Examples of the voluminous zoot suit may have also been remade into other garments, or the suits simply may not have survived use, whether from day-to-day wear or nighttime dances of the fashionable jitterbug or Lindy Hop. Further, during the zoot suit riots that first began in Los Angeles before spreading to other urban areas of the country, servicemen actively sought out Chicano and black zoot-suiters, sometimes even using ‘zootbeaters’ – a wooden two-by-four with nails – to physically tear the suits off of the zooter in a deplorable act of public humiliation.

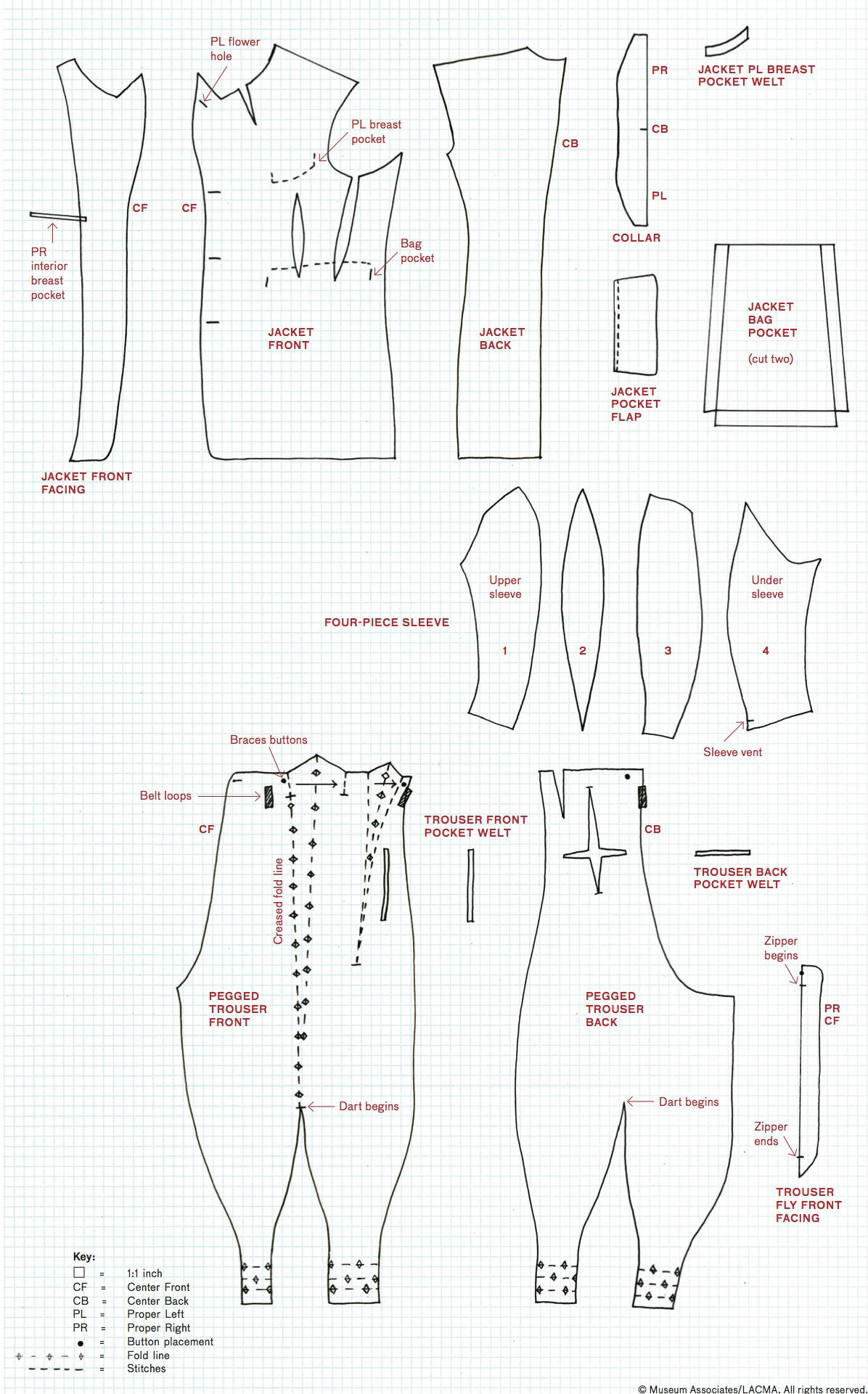

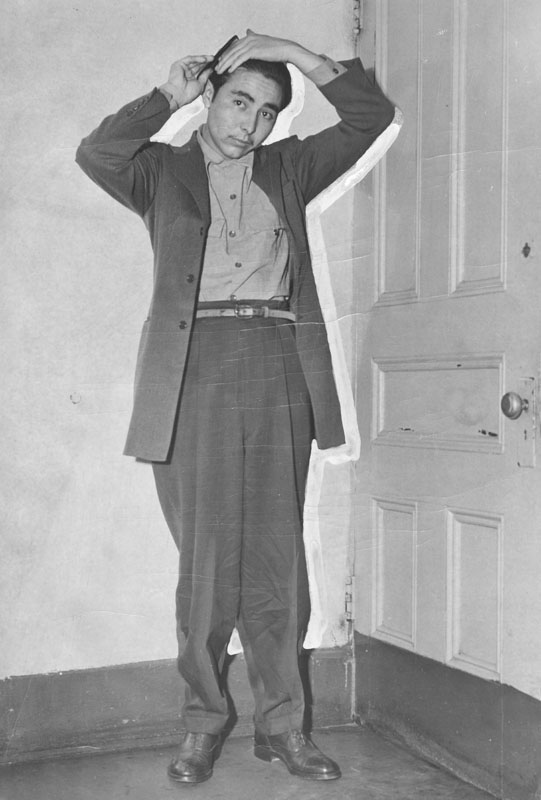

Despite the turbulent past of this garment, remarkably, one extant zoot suit survives in the permanent collection at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. LACMA’s zoot suit is not only one of the only known suits of its kind held within a museum collection, but it is an extreme example of an already overstated style at that. The jacket of the zoot suit has a strong, overtly broad shoulder line, a fitted waist, a long jacket hem that falls below the fingertips and wide, pegged sleeves. To further exaggerate its fullness, the sleeves of this rare multi-striped suit are inset with gores in a contrasting striped fabric. The bag pockets of the jacket only attach at the top flap, allowing them to fly out from the body when the wearer spun. The matching pegged trousers are worn high on the waist and closed with a seventeen-inch zipper fly. For maximum fullness at the knee, the waist of the trousers is deeply pleated; this example has a two and a half-inch knife pleat at both sides of the center front which allows for the pant leg to billow out into a forty-seven-inch circumference knee before it tapers in with curved darts into a narrow cuff, measuring a mere seventeen and a half inches.

Other construction details, such as the quality of the wool fabric, the stitch length at the seams and how details such as the collar and armscyes are tailored, suggest that the suit was made by a seasoned professional tailor. However, the textile is not of the finest quality and the sartorial hand was not typical of high-end suits. For a young man who wanted to don the uniform of hipsters or hepcats, but could not afford a costly bespoke model, this example – made to the tall size of its original owner – may have been semi-custom made, a common method of purchasing zoot suits. In this process, a retailer took the customer’s measurements and sent them to a wholesale manufacturer that constructed the suit to specification. Although these semi-custom suits were more affordable than custom tailoring, the cost was still expensive for most working-class youths who often purchased a suit on credit.1 The sheer extravagance in the draped shape of this suit suggests that it may have not only been semi-custom made, but also worn for performance, as the wearer would have generated such movement and presence in the pegged ensemble.

Through thorough analysis of materials in the suit, the suit is likely authentic to this turbulent early 1940s period.2 The presence of lead in some of the original trouser buttons suggests that they pre-date recent times. Though buttons could be removed and replaced, the use of both belt loops and suspender buttons in the construction of the trousers supports this date, as men were still transitioning from suspenders to belts to hold up their trousers; it was typical in the 1940s to have both options available. Also, the rayon lining of the jacket ends half-way up the interior top back with exposed seams finished and bound with fabric bias tape, tailoring details typical of men’s suits of the 1930s and 40s.

Upon examination, there is also physical evidence throughout the suit that it was worn and likely danced in. Aside from remnant tobacco found in the pockets when it first arrived, or slight signs of wear throughout, such as loose threads and warping, there are patches at the back cuff of the right pant leg from considerable wear. In the jitterbug, it is common to actively kick your dominant leg – the force of spinning into a kick may have caused the bottom cuff of the pant leg to slip past the ankle and catch on the heel of the shoe. If this is the source for this wear, we might conclude that our original zoot-suiter was right handed. Incidentally, the aforementioned tobacco was also found in the right jacket pocket.

The piece itself was originally found by a collector and jazz enthusiast who discovered the suit in an estate sale of a house that he described as a ‘time capsule’ in Montclair, New Jersey, just twenty minutes by car outside of Harlem, likely where the suit was worn. Harlem was the home of the Savoy Ballroom, a public dance space considered ‘The Heartbeat of Harlem’ by poet Langston Hughes. The venue played jazz music and – unlike the Cotton Club – it always had a no-discrimination policy. Thus, the general styling of accessories for the zoot suit for display was based on research done from photographs of young men and jazz musicians primarily from the New York area.

The deep-seated meaning of this exaggerated style to those who wore them from Harlem to Los Angeles was of self-assertion. Not only did zoot-suiters form a community around this suit, but the pleasure of assuming this bold draped look spoke to young African American and first-generation American men who were systematically underprivileged. But for many white Americans, the zoot suit was symbolic of gang activity or subversion, especially as racial tensions continued to rise, particularly in southern California against Mexican-American pachucos. In 1942, the Los Angeles press began to report on the Sleepy Lagoon Trial against a Chicano zoot-suiter accused for the murder of another Chicano youth; the negative press fostered intense prejudice towards the Mexican-American community. Accounts of pachuco gangs assaulting visiting white servicemen stationed in Los Angeles for deployment overseas abounded, as were rumours of these servicemen seeking out young Chicano women for sexual pleasure.

In June 1943, fights broke out between pachuco zoot-suiters and navy service men, with hundreds of Chicano and African-American youths beaten and arrested. Some accounts even described ‘prowl cars’ which cruised through Mexican neighbourhoods to intimidate the community. Some press sensationalised these ‘zoot suit riots’ with articles entitled ‘Zoot-Suit War,’ and ‘Zoot-Suiters Learn Lesson in Fight with Servicemen.’ The race-related zoot suit riots spread to other cities, such as Detroit, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Richmond and Harlem. In June 11, 1943, The Nation voiced dissent towards the press’ unbalanced reporting of the riots in an article under the headline, ‘Hearst Press Incited Campaign Against Mexicans, Promoted Police Raids, Whipped Up Race Clashes.’ In the article, the columnist called out the press for its ‘great smear campaign against Mexicans.’3 This historically left-leaning periodical continues with the bold observation, laden with suggestive comparisons with the war overseas, that, ‘There is a deadly parallel between the pictures of naked Mexican boys lying on the streets of Los Angeles in pools of blood – with grinning mobs standing around – and the pictures one began to see a few years ago of Jews being made to clean the streets of Vienna.’4

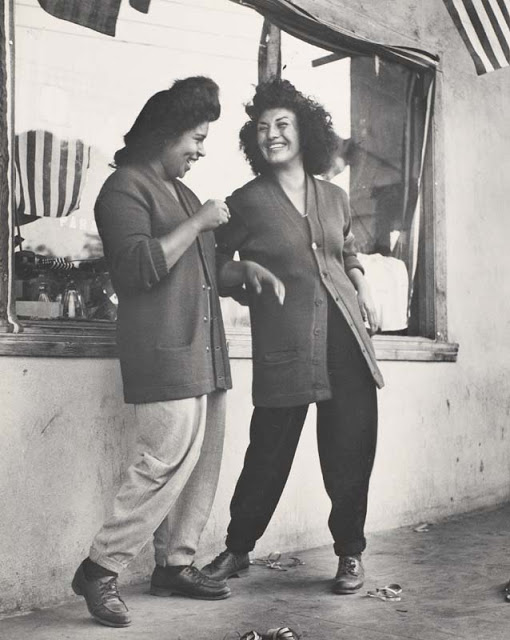

As difficult as this period was for pachuco young men, it was similarly challenging for their female counterparts, the pachucas. Like the pachucos, pachucas also received negative press amid the riots, with various reports of these young Chicano women battling servicemen amid the riots alongside their brothers, boyfriends, or friends, or attacking white women with knives that were allegedly hidden in their hair. These so-called ‘zoot suit gangsterettes,’ ‘cholitas,’ or ‘zooterinas’ were also said to be part of gangs called the ‘Slick Chicks’ or ‘Black Widows.’

Their look was similar to zoot-suiters, and generally consisted of a broad-shouldered ‘finger-tip’ coat, a short knee-length skirt or pegged trousers, fishnet stockings or bobby socks, platform heels, saddle shoes, or huarache sandals, high pompadour hairstyles, and heavy make-up. Latino/a historian Elizabeth R. Escobedo notes that strong lipstick and eye make-up was a means for these young women to actively embellish the Mexicanness of their face.5 In some cases, pachucas assumed this look as an act of rebellion. As first-generation Mexican-Americans, they were redefining their place in society – not only as ethnic minorities, but also as women from a cultural heritage strongly dominated by traditional Catholic values. Assuming a more masculine look with the zoot suit allowed these young women to rebel against what was expected as a Mexican female, while also being a means of community for other like-minded Mexican-American women.

Like any curious young adult, some pachucas were confrontational and sexually provocative as reported in both English- and Spanish-language press; however, other pachucas donned the zoot style simply because they wanted to be fashionable and visually affiliated with the latest youth trends. According to oral histories of Chicano women who grew up in southern California in the 1940s conducted by Catherine S. Ramirez, some wearers of the style did not even self-identify as a pachucas.6 As the zoot suit grew to be more of a fashion fad, even white females – like white males – began to don the style. In fact, when zoot suits were depicted on white men and women, the emphasis of the style was more on youth, music and dance rather than gang violence. In 1942, the St. Louis Post Dispatch described wearers of the style as ‘usually excellent dancers, perfect gentlemen,’ and that their female counterparts call their zoot look ‘a “juke jacket,” because it’s worn when dancing to the juke box.’7 It is worth noting that all zoot-suiters photographed in this article were Caucasian.

This clear double standard of the race of the zoot-suiter was so notable to many in the Mexican-American community – both parents and young women alike – that they actively discouraged the style, especially on women. Some in the Mexican community even feared the pachucas. Over time, the concern grew that all young Chicano women would be generalised as delinquent and gang-affiliated. In an effort to prove false assumptions of their sexual promiscuity in particular, a group of thirty Mexican-American women from various neighbourhoods in Los Angeles came forward and offered to undergo medical examinations to prove their chastity. 8 Though self-identified as ‘zooters’ they wanted to demonstrate that their style of dress and sexual actions did not go hand-in-hand. Fortunately, leaders of the Mexican community deemed such extreme measures to be excessive and instead asked that they donate blood to the Red Cross. The Los Angeles-based Eastside Journal, published an article highlighting another group of Mexican-American girls, all of whom graduated with top honours and with brothers or boyfriends in the armed forces.9 None were pictured wearing a zoot suit, but this was clearly a way to use the press, which had vilified zoot-suiters, to counteract the hysteria around pachucas.

Although the zoot suit fell out of fashion for both men and women by the end of World War II, underlying social issues of race would continue to evolve. Despite being a short-lived fad, this draped shape is an icon of its time and considered the first truly American suit. It was an exaggeration of the ultimate male uniform, the suit, and in its heyday the zoot suit was adopted widely in various communities throughout the country. During its reign in fashion, it not only granted its wearers, both male and female, a sense of strength and bravado, it also put a spotlight on the true diversity of American citizenry.

Clarissa M. Esguerra is Associate Curator of the Costume and Textiles department at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Her curatorial contributions include ‘Fashioning Fashion: European Dress in Detail 1700-1915’ and, most recently, ‘Reigning Men: Fashion in Menswear 1715-2015,’ where an early 1940s zoot suit was a prominent feature.

K Peiss. Zoot Suit: The Enigmatic Career of an Extreme Style, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, 2011, p. 25. ↩

This analysis was carried out by LACMA textile conservator Laleña Vellanoweth and conservation scientist, Charlotte Eng. ↩

C McWilliams, ‘The Story Behind the Zoot War:’ Hearst Press Incited Campaign Against Mexicans, Promoted Police Raides, Whipped Up Race Clashes,’ The Nation, June 11, 1943, p.3. ↩

Ibid., p. 4. ↩

E R Escobedo, ‘The Pachuca Panic: Sexual and Cultural Battlegrounds in World War II Los Angeles,’ Western Historical Quarterly, Vol. 38, No. 2, Summer, 2007, p.140. ↩

See C S Ramirez, The Woman in the Zoot Suit, Duke University Press, Durham and London, 2009 ↩

“The Government Frowns on the ‘Zoot Suit,’” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 27, 1942, p. 9. ↩

E R Escobedo, ‘The Pachuca Panic: Sexual and Cultural Battlegrounds in World War II Los Angeles,’ Western Historical Quarterly, Vol. 38, No. 2, Summer, 2007, p.142. ↩

C S Ramirez, The Woman in the Zoot Suit, Duke University Press, Durham and London, 2009, p. 44. ↩