My mother tells a story about wheeling me around in a supermarket shopping cart as a toddler, wearing so many tops and T-shirts simultaneously that my arms stuck straight out like a snowman. She had let me choose my clothes, and whenever she tells the story, her face beams with pride. I imagine she tells it to illustrate how, even as a baby, I had strong opinions and a singular fashion sense.

When I became a mother this story hit differently. I stopped imagining how cute and funny I must have been, and began considering my mother. It’s 1981, her hair is most definitely permed, and I’m her first child. I can just see us sitting on the floor together navigating all those sleeve and head holes. I imagine my mother helping me squeeze into layer after layer with loving devotion and deep respect for my vision. She must have had such a laugh, or else she was worn down by my passionate insistence. I envision the tickled look on her face for having made my sartorial dreams come true, and then devotedly charioting me around our South Florida Publix like an overstuffed Cleopatra.

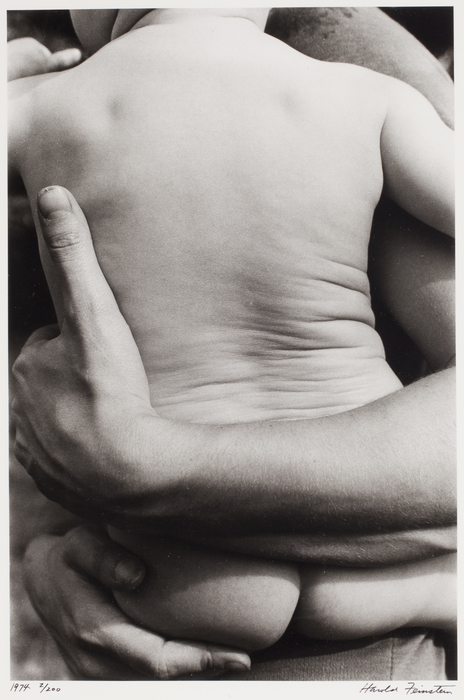

Getting our babies dressed is one of those things. We don’t think much about it, but it’s something we do daily, sometimes even several times a day, for years. For a time at least, we choose what to dress our children in and when and how they wear their clothes. We keep tabs on their cognitive and physical growth by noticing when our babies are able to offer a helping hand or when certain garments simply can’t be squeezed into any longer. Dressing is an intimate bodily exchange, a choreography involving touch, will, cooperation and consent. As an act of care, dressing is a simple yet monumental routine that helps to form a relationship. This budding relationship is in the details – it’s the feel of a hand, the texture of fabric, an exchange of words and eye contact, the way one body guides another.

Unlike feeding or sleeping, the ‘how to’ of dressing children doesn’t get much airtime in the deluge of parenting advice. What’s out there centres around the clothes themselves – styles, brands, cost, material, weather suitability. These considerations matter. But the act of dressing a child isn’t as simple, intuitive or easy as it might seem. Dressing is, after all, a relational activity, a place for exchange. Until an infant’s nervous system regulates and movements are controlled, a child is entirely dependent on their caregiver to dress them. As our children hone new skills and their drive for individuation revs, we carers empower them to put their own clothes on. Offering a child the chance to choose what to wear can be empowering or overwhelming. Choosing socks might seem simple, and to some extent it is, but it can also shape one’s experience of care, agency, language, dexterity, even style. At best, forming a relationship around clothing can be an incredible source of hope, love, joy, pride and connection. At worst, it’s a chore, a source of tension or even a struggle. Like any life skill, being intentional about how we lead our children in the act of dressing has a profound impact on other areas of their lives.

When I ask my mother to tell me more about dressing me, she explains she wanted me to make as many choices for myself as possible. She believed that allowing me to choose what to wear and helping me to put my clothes on as I wanted would encourage my innate creativity, bolstering my sense of agency and self advocacy. My mother wasn’t afforded the luxury of self determination as a child, and found it stifling and alienating. She wanted to raise someone liberated, creative, and who knew themselves. And she saw getting dressed a sure path toward her goal.

Parenting advice in the 1980s wasn’t as ubiquitous as it is today, but my mother found her people in the company of single moms (since she herself was one) and I imagine she must have discussed the topic of dress within her circle. Some of her ideologies may have resulted in my looking ridiculous. There’s a photo of me at my grandfather’s house wearing a toy stuffed cat as a stole, which I thought looked really smart paired with my purple taffeta dress and a single red glove. Still, I chose what to wear within the confines of what was available to me, and my mother had most of the control over the items in my closet. (When I discovered the joys of thrifting as a teenager however, all bets were off.) My mother and I had our run-ins, but to her credit, she held her tongue when it came to how I dressed myself. When I look back, it’s clear that beyond control or aesthetics, she valued our relationship and my burgeoning sense of self.

When writing and editing Designing Motherhood, I began collecting parenting books from past decades, and I now have a pretty substantial collection.1 A classic in the genre is Bringing Up Bébé by Pamela Druckerman (2012). Druckerman doesn’t touch upon dress per se, but she does touch on the topic of choice. ‘C’est moi qui décide!’ ‘It’s me who decides!’ French parents said it so often that Druckerman titled an entire chapter over the concept. She explains that while Anglophone parents worry about being too strict will break their kids’ creative spirits, French parents say these phrases to remind both their kids and themselves who’s the boss. ‘Still,’ Druckerman writes, ‘there are no hard and fast rules. It’s about setting limits, but also about observing your child, building complicity, and then adapting to what the situation requires.’

There is a lot of justified critique of so-called experts who, over the centuries, have aimed advice at caregivers. I’ve found that at least since the ancient Greek physician Soranus penned his recommendation that mothers swaddle and salt their babies, what to dress babies in has been a major topic. But the how of dressing – and navigating the cultural or psychological aspects of it – is much less common.

By the time The Mothercraft Manual (1917) was first published, swaddling clothes were listed under the heading ‘Harmful Equipment.’ Loosely fitting children’s clothes were now advisable, and Mothercraft included instructions for making baby-sized kimono coats, raglan sleeve slips, and slip nightgowns with fastening snaps. Like other advice manuals of the time, technical details surrounding fit and seasonality fill the pages. Nowhere, however, does the craft aspect of mothercraft extend to the actual act of dressing a child.

An exception was Dr. Spock, whose Common Sense Book of Baby & Child Care books, first published in 1946, told parents to listen to their guts. ‘Trust yourself. You know more than you think,’ Spock famously said. His section entitled ‘Let him enjoy his duties’ was reworked in later editions, but in 1955, he explained how when it came to dress, patience and tact could go a long way: ‘If you don’t let him do the parts he is able to, or interfere too much, it’s likely to make him angry. If he never has a chance to learn at the age that appeals to him, he may lose the desire. Yet if you don’t help him at all, he’ll never be dressed and he may get frustrated at his own failure. You can help him tactfully in the jobs that are possible. Pull the socks part way off so the rest is easy…Interest him in the easy jobs while you do the hard ones. When he gets tangled up, don’t insist on taking over but straighten him out so he can carry on. If he feels that you are with him and not against him, he is much more cooperative. It takes patience, though.’2

Lingering over the actions and intentions of care is a rarity in most advice manuals. The word ‘parenting,’ used as a verb, didn’t come into common usage until the 1970s, when an American minister and psychologist Fitzhugh Dodson penned the book, How To Parent (1971). Dodson was a far cry from Spock. For him, parenting meant combining science with the principles of animal training, and he gave a hearty endorsement of spanking.3 These days, parenting’ sometimes refers to what parents do, but more often the word is associated with what they should do, intensifying many parents’ feelings of inadequacy.

There is no one way to dress a baby, just as there is no one way to parent one. We all bring our social and cultural locations to the job. In addition to the home environment, an enormous amount of a child’s fate is determined by luck, accidents of birth, socioeconomics, and geography. Today’s parents are navigating the traditional hardships of parenting – worrying about money and safety – as well as new stressors, including screens, a youth mental health crisis and fear about the future. All of this is compounded by an intensifying culture of comparison, often amplified online, that promotes unrealistic expectations of what parents must do. Chasing these expectations while navigating an endless stream of parenting advice has left families feeling exhausted, ashamed and perpetually behind.

Caregiving is crucial, but there’s no way to map a single approach onto the messiness of an individual child. In 1953, British psychologist D.W. Winnicott pioneered the concept of the ‘good enough’ parent in part to protect against the anxiety that was arising in the face of new professional advice. Still, mustering the internal resources to be intentional in the way we give care is worthwhile. In American theorist bell hooks’s book All About Love (2000) she describes having her physical needs being met as a child, but seldom with love, a circumstance she feels had lasting repercussions. ‘Schools for love do not exist,’ she writes. ‘Everyone assumes that we will know how to love instinctively… And we spend a lifetime undoing the damage caused by cruelty, neglect, and all manner of lovelessness experienced in our families of origin and in relationships where we simply did not know what to do.’ hooks sees care as but one ingredient in love – she also includes affection, recognition, respect, commitment, trust, and honest and open communication. So might getting dressed be a place to explore loving care in all its messy permutations?

When I first became pregnant a decade ago, I ignored warnings from superstitious friends and travelled the boroughs of New York City thrifting baby clothes. Admonitions about counting my chickens be damned. I couldn’t wait to dress my baby. I created a thrifted layette consisting of vintage knitwear, embroidered kimonos, and bonnet that I could tie in a bow.4 Within days of my daughter arriving, those delicate pointelle suits I had so lovingly washed and ironed were forever tinged with meconium, that tar-like dark green poop made up of protein, fats, and intestinal secretions that infants expel during their first days.

Among the other shocks that came with becoming a mother, I received a swift lesson on the importance of sartorial practicality. Yet I loved dressing my baby. I made an art form out of pushing my thumbs through miniature arm holes, scrunching up the fabric only to let it unfurl over her tiny hands, arms, elbows and shoulders like a locomoting caterpillar. Instinctively, I talked her through the act, saying things like ‘Okay, other arm now’ or ‘It’s time to put your shirt over your head.’ I noticed that when I dressed her in a hurry, she’d reject dressing, crying while arching her back in whitehot frustration. ‘It’s so disappointing,’ I wrote in my journal after one such occasion, “Alice hates getting dressed!” She was, at the time, three months old.

We left for Budapest in March, just before Alice’s half birthday. I was researching twentieth century Hungarian school design, and my husband and I agreed that the intriguing city with crumbling Art Nouveau architecture and Brutalist swimming pools seemed like as good a place as any to care for an infant. Hardly knowing anyone and barely speaking the language was equal parts isolating and enrapturing. We mostly experimented in the dark. Because this was the early days of online parenting advice and none of the English language bookstores stocked anything relevant, we learned to embrace imperfection and trust ourselves. We struggled plenty (mostly with sleep) but were also smitten by our child and our lives together and were developing confidence as parents.

When a new friend invited me to join a weekly parent-infant group based on the work of Emmi Pikler, I found myself thrust into a world where caregiving was considered a skill, a craft, a science and an artform all at once.5 Pikler was a radical in her day. As a paediatrician in the 1930s, she insisted on direct communication, consent and bodily autonomy. She wrote prolifically about every aspect of caregiving, and emphasised the relationship between caregiver and child. Pikler had a keen design sensibility, and created furniture, play objects, clothing and even footwear to make the lives of carers and children easier. But she also advocated for presence, eye contact, intentional and respectful touch and words, and cooperation. In the Pikler-based parent-infant group I attended, I observed content and peaceful babies exploring their environment and met caregivers who were building authentic relationships with their babies.

Authenticity was a shockingly simple parenting strategy, and yet finding the balance between leadership and partnering – a Pikler-inspired concept – was incredibly difficult for me. It felt worthwhile though, and I practised. To make it right for my family and not get too overwhelmed, I ignored what felt too meticulous, and focused on the areas that resonated – namely the relationship I was forming with my child. With this new lens, getting dressed could be a luxuriously unhurried activity, a pleasurable time for us to learn and connect.

At home and at the parent-infant groups (both in Budapest and then in Brooklyn where I discovered RIE, the American Pikler-offshoot founded by Magda Gerber, I practised sensitively observing Alice. She was so capable! So interested in the world! Thanks to what I was learning from Emmi Pikler and Magda Gerber’s teachings and groups, I focused on touch, communication, and the positions she preferred to be in. Getting dressed each day was process oriented, as much about reciprocity as it was about putting on clothes. And I found dressing a great way of knowing Alice. I also tried to be present through her myriad experiences. We often relied on humour, which to this day is one of my favourite things about our relationship. When she protested, I didn’t have to solve her upset or change my goals. I was leading our dance, but could sensitively respond and move through the experience with her. I particularly enjoyed setting us both up for little successes by arranging garments in ways that made things easier and more pleasurable for us both. Soon, I noticed that when I’d offer the trousers, she’d offer a foot. Because I am also human, I regularly lost all this intentionality when I was distracted, impatient or in a rush. I also willingly and regularly abandoned the whole thing when I felt that I was getting toxically perfectionistic. But slowing down, staying in the moment, and building an authentic relationship felt worthwhile. It became a longterm practice, like meditation, a north star for how things could be.

Alice is now ten, and has a younger sister and brother. Over the past decade I’ve experimented with many of Emmi Pikler and Magda Gerber’s concepts, especially in the context of getting dressed. (I have also woven the core principles into my professional life, and have since trained to facilitate parent-child groups). Each of my children is unique and it’s been fascinating to observe how each of them respond to getting dressed. My two-year-old son Jules, for instance, loves gloves the way that other toddlers love train sets. While other kids may sleep with a special stuffy at night, Jules cuddles a pair of ski gloves. Along the way, I’ve learned to delight in his enthusiasm for oven mitts, gardening gloves, rubber cleaning gloves, and fox-shaped mittens. His love for gloves could be a toddler quirk, or it could indicate tactile defensiveness, a sensory sensitivity that often manifests with getting dressed and the feeling and fit of clothing. Getting dressed requires us both to slow down and accept what comes.

I have made certain departures from the way my mother raised me that, oddly enough, veer into the territory of French parenting: the kids choose what to wear at home, but we must agree about what to wear when we leave the house. Because we have found freedom in the boundaries we create, their dad and I do our best to change the contents of our children’s drawers as the weather changes to minimise struggles. As it does for us all, too much choice can overwhelm a child. So we limit the options (‘white socks or blue ones?’). We also regularly make mistakes and exceptions. I have been known to allow my son to wear my great Aunt Phyll’s hand-me-down evening gloves on the way to the playground because it makes for a smoother journey. And that’s a kind of loving care too.

It’s time that getting dressed receive its due. At any age, it can be the basis for a pleasurable and authentic relationship, imparting confidence, language acquisition, satisfying relationships, and a greater sense of self. What is so often seen as merely practical or aesthetic might also be understood as deeply meaningful and powerfully expansive. It can also reflect one’s values or culture – there’s no one way to dress, or get dressed. Caregiving, too, is cumulative, and happens over the course of years. Some conflict, negotiation, even rupture is inevitable, part of the fabric of care. It’s never completely smooth. As the world comes to terms with the immense task of preparing populations for the future, it’s the big things – food security, housing, decarbonising our planet – but it’s the little things too: help with a shirt, choosing which sleeve to put on first, eye contact. We have more ability than is commonly imagined to shape the kinds of families and communities we experience in the future. Dressing with intention can fit any culture, any socioeconomic class, and any caregiver-child dyad, including those with special needs or disability. Childrearing advice, as it has been presented and experienced over the last century, has brought with it plenty of problems. Chief among these is the issue of overthinking care. But overthinking and intentionality are not the same. The premise that being intentional about how we parent is bound to be part of the problem, rather than a way of better enjoying or being with our children, is a myth we must outgrow. Finding connection in care looks different for everyone, yet is surely sound advice for us all.

Michelle Millar Fisher and Amber Winick, Designing Motherhood: Things That Make and Break Our Births. MIT Press, 2021. ↩

Benjamin Spock, Dr. Spock’s Baby and Child Care. The Bodley Head, p.325 ↩

‘Some of you may have heard the old saying “Never spank a child in anger.”‘ Dodson writes. ‘I think that is psychologically very poor advice, and I suggest the opposite: “Never strike a child except in anger.”‘ ↩

The English language term ‘layette’ has been used since the mid-19th century to describe a collection of clothing and accessories for a newborn baby. The word comes from the French word laiete, which means ‘small coffer.’ In the 1920s, it became common for expectant mothers and their loved ones to knit matching layette sets, which often included a blanket, hat, sweater, and booties. Traditionally, women would hand-sew or knit their baby’s clothes during pregnancy. ↩

Pikler was also commissioned by the Hungarian government to create Lóczy, a research centre and orphanage, where she honed her philosophies about caregiving. ↩