THERE IS A TENDENCY, across fashion exhibitions and publishing, to portray the fashion designer as a creative genius. The ‘Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty’ exhibition at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum in 2015, for example, emphasised its demonstration of ‘the extraordinary talent of one of the most innovative designers of recent times.’1 Such a depiction positions the designer outside the realities of the fashion system, as a uniquely autonomous figure of otherworldly measure: as god, or king. While this mode of representation may be customary, even habitual, it is deeply misrepresentative of the designer, and the contemporary fashion system in which their work resides.

Curators of the 2014 Dries Van Noten exhibition ‘Inspirations,’ held at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, asserted that the show would reveal the creative fashion design process by way of an exploration of Van Noten’s many individual inspirations – the garments were accompanied by images, sculptures, fabrics, music and found objects that spoke of Van Noten’s inspiration gathering. In both this exhibition and its second iteration, at Antwerp’s Mode Museum in 2015, visitors were invited to partake in ‘an intimate journey into [Van Noten’s] artistic universe [which would reveal] the singularity of his creative process.’2 Reviewing the exhibition for Vogue, Hamish Bowles wrote that the show was a ‘magical tour to unwrap the mysteries of Dries’ passion, process, creativity, and singular talent.’3 Thus, this exhibition, like ‘Savage Beauty,’ constructed a deep sense of worship to the creative talent of the individual fashion designer. This curatorial approach, beginning, fashion historian Valerie Steele suggests, with the seminal 1992 exhibition devoted to the talent of Gianni Versace at the Design Laboratory at Fashion Institute of Technology in New York, has become ‘the most immediately accessible and popular type of fashion exhibition.’4

Recent publications, such as Dana Thomas’ 2015 book Gods and Kings: The Rise and Fall of Alexander McQueen and John Galliano and Andrew Wilson’s 2015 biography Alexander McQueen: The Blood Beneath the Skin, have sought to reveal a more personal, human side of the fashion designer and debunk this status as otherworldly creative genius. However, such texts are regularly met with critical response. In reaction to Thomas’ publication, fashion reporter Alexander Fury wrote for the Independent that it was a mere ‘exercise in muck-racking.’5 Sarah Mower also declared in The Guardian that it was ‘calculated to fire hatred.’6 And Cathy Horyn claimed in The New York Times that Thomas presented ‘her subjects one-dimensionally, as a kind of British double act of talent destroyed.’7 This criticism was in large part, according to Horyn, due to its lack of recognition of the subjects as ‘special cases, as true artists.’ If Thomas’ text trivialised the talent of these two designers, Wilson’s text made far more of McQueen’s extraordinary talent. However, Wilson also exposed a childhood of abuse that McQueen was careful to conceal, the result of which, Mower wrote, being the sense of ‘raw wounds ripped open.’ What is true of both publications is that they similarly employ the romantic notion of fashion designer as sole creative genius as their point of departure for exploring the lives of their subjects. The construction, in these texts as in exhibitions, of the designer as creative celebrity relies upon the myth of solitary design genius in order to garner audience curiosity.

Media coverage of fashion designers therefore presents two paradoxical figures: on the one hand, that of the designer as genius, and on the other, the designer as flawed human figure. This tension evident in both fashion biography and in the numerous exhibitions of recent years, is a point of much contention. Of course, the notion of ‘creative genius’ is not solely reserved for fashion designers. All manner of creative individuals have long been elevated to genius status by authors, curators and marketing managers as a story-telling and audience-gathering technique. What is interesting about this notion of fashion designer (or artist, or musician) as genius – as god or king – is the way in which it is promoted for commercial ends, in not only in the publishing industry but also in the museum and art gallery setting. Fashion continues to hold a somewhat precarious position in the gallery space, and in relation to art, and by presenting designers in this way, fashion seeks the status of high art to legitimise itself in the sanctified realm of the museum. As such, the genius mantle is used as both justification and vindication.

This genre of fashion exhibition, in evidence not only in ‘Inspirations’ and ‘Savage Beauty,’ but in other recent shows including ‘Charles James: Beyond Fashion’ at the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art Costume Institute in 2014, ‘Patrick Kelly: Runway of Love’ at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 2014 and ‘RED Comme des Garçons: innovation, provocation’ at London’s Live Archives in 2015, is a lucrative template for major galleries, attracting record-breaking punters and delivering substantial financial return. This return is not only directed to the institutions by way of audience numbers, but also towards the design houses involved. However, as fashion journalist Suzy Menkes points out, despite great economic return, ‘almost no fashion exhibition could take place without some external investment.’8 This investment, Menkes continues, frequently comes by way of brand sponsorship. Arts journalist Ellen Gamerman suggests that ‘for luxury companies, museum exhibits are becoming an important new tool in their marketing arsenals.’9 Thus, art institutions exhibiting fashion regularly become caught between the ethics of commercial and creative imperatives, as well as the demands of designers in terms of exhibition content, structure and promotion. These ethical conundrums undoubtedly effect the tone of the final exhibition, often rendering it more a press gesture than a critically curated exhibition of the designer’s work.

While the production of an exhibition that touts the fashion designer as individual artistic genius may be of great economic benefit to the institution putting on the show, or to the author selling the book, it unfortunately also perpetuates a disconnect from fashion designers that, as Steele notes, indicates ‘a profound misunderstanding of the fashion process.’10 The fashion designer does not stand outside of the fashion system as a lone ranger. Rather, the designer is but one participant in the vast network of social relations that make up the fashion process. Fashion theorist Yuniya Kawamura suggests that to focus on the individual designer as unique creator ‘writes out of the account the numerous other people involved in the production of any work, and also draws attention away from the various socially constituting and determining processes involved.’11 Indeed, the construction of the myth of the fashion designer as genius offers little in terms of a reflection of the workings of the contemporary fashion system, particularly in the context of today’s industry constantly in flux, with fashion designers ever more pliable to the whims and desires of conglomerate brand directors.

Deconstructing the myth of the fashion designer as a solitary creative genius need not belittle a designer’s extraordinary talent and vision. Rather, in recognising the role of the fashion designer within the multifaceted fashion system it is possible to acknowledge this talent without resorting to the extremes of either worship or ‘muck-racking.’

Harriette Richards is Melbourne-based Kiwi currently undertaking a PhD in cultural studies at Western Sydney University.

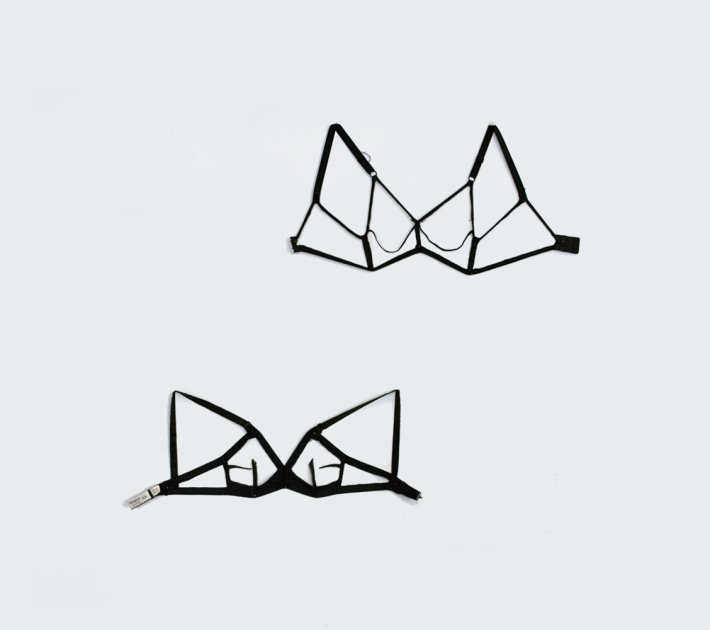

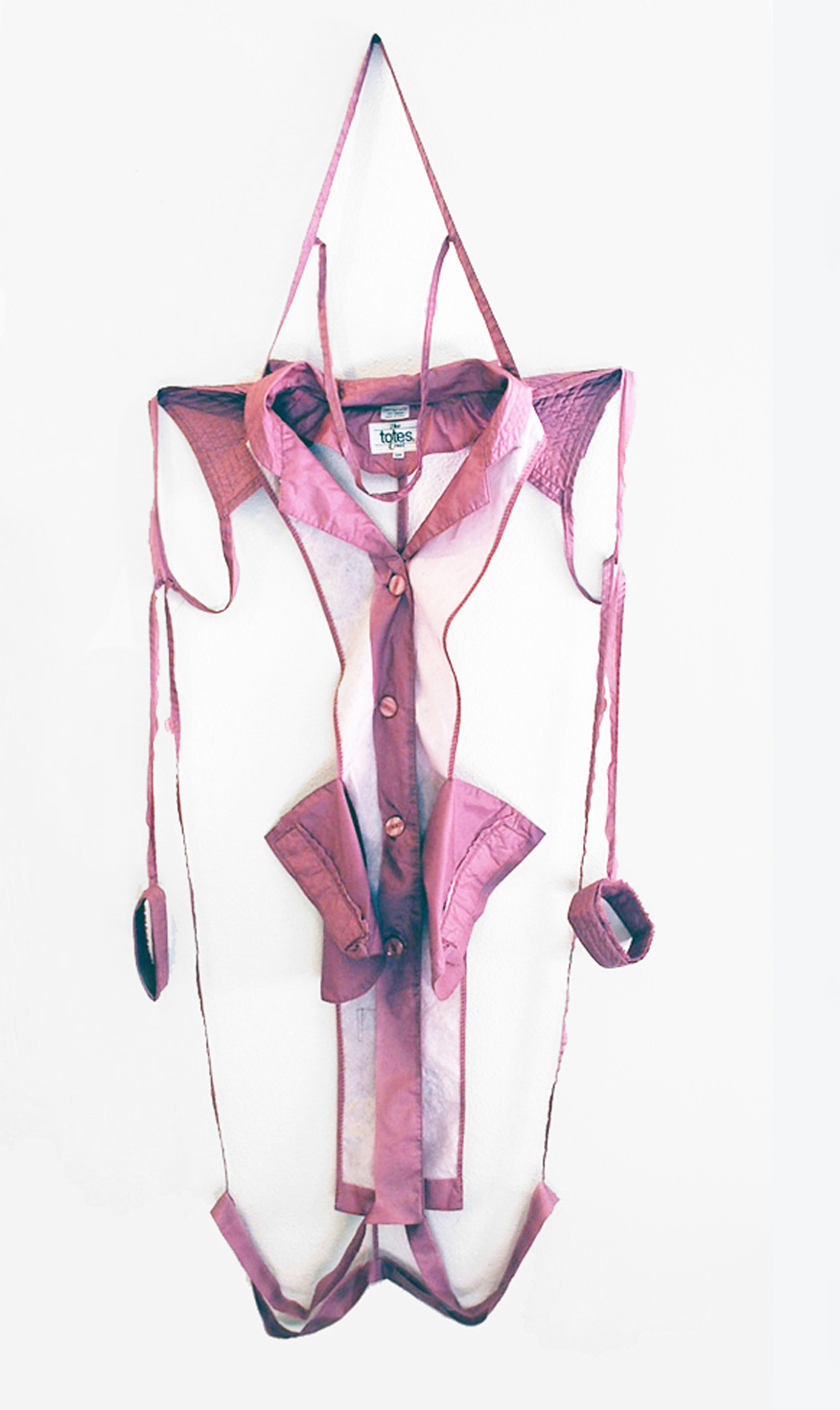

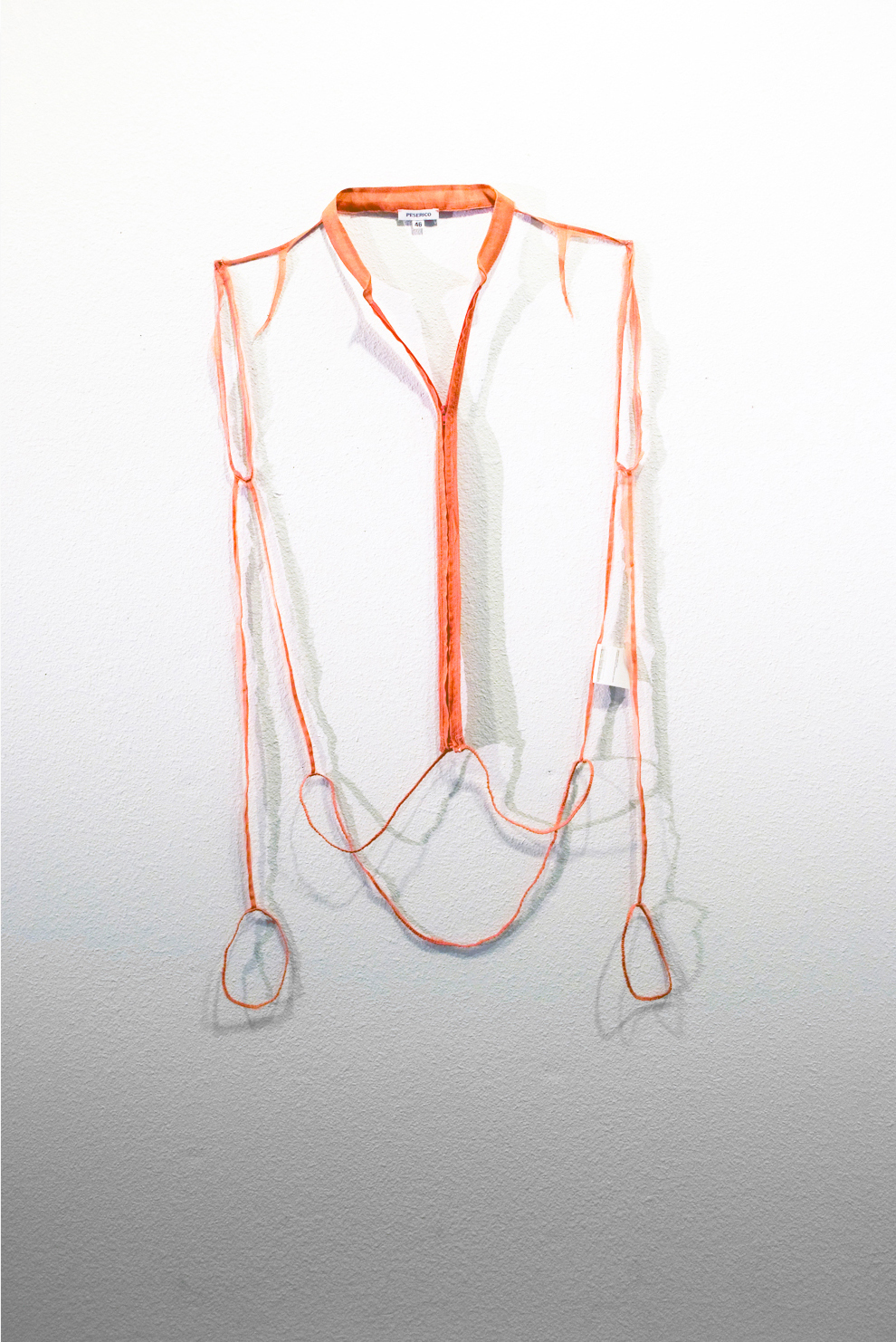

Silvie Deutsch is an American artist, all images shown here are from her 2010 series ‘Seam Drawings.’

http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/exhibitions/exhibition-alexander-mcqueen-savage-beauty/ ↩

http://www.momu.be/en/tentoonstelling/dries-van-noten.html ↩

http://www.vogue.com/866584/dries-van-noten-inspirations-exhibition/ ↩

V Steele, ‘Museum Quality: The Rise of the Fashion Exhibition,’ in Fashion Theory, 2008, 12:1, p.15. ↩

http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/books/reviews/gods-and-kings-by-dana-thomas-book-review-exposing-the-seams-cruelly-10011203.html ↩

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/feb/22/gods-and-kings-alexander-mcqueen-john-galliano-dana-thomas-beneath-the-skin-andrew-wilson-brutal-bio ↩

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/08/books/review/gods-and-kings-by-dana-thomas.html?_r=0 ↩

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/07/05/fashion/is-fashion-really-museum-art.html?_r=0 ↩

http://www.wsj.com/articles/are-museums-selling-out-1402617631 ↩

V Steele, Paris Fashion: A Cultural History, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1988, p.9. ↩

Y Kawamura, Fashion-ology: An Introduction to Fashion Studies, Berg, New York, 2005. ↩