Vintage has never been more visible, but that doesn’t make it any easier to define. There were never hard-set rules around what constitutes vintage versus just old or second-hand. The timeframe is always in flux, and depends on what generation you’re coming from. I remember when the standard was thirty years old, now I mostly hear twenty-five. When it comes to designer collections it’s typically ten, but the term ‘archival’ is also coming into vogue. There’s also the newer and somewhat divisive ‘true vintage,’ meaning 1930s through midcentury but is also used for anything pre-dating the fast-fashion era. If there’s a silver lining to any of this, it’s that none of it ultimately matters – there are simply more sub-genres and greater specialisation for those who seek it. This plurality extends to vintage clothing shows, which have also been multiplying at a rapid rate.

One newcomer to the vintage show circuit is Distressed Fest. It is the offspring of Abe Lange, a collector and dealer with a showroom space in Brooklyn who has since partnered with Connor Hayes Gressitt, a self-described dumpster diver and proprietor of the San Diego showroom Le Garbaage. Twice a year, fall in Los Angeles and spring in New York, Distressed Fest unites over thirty dealers specialising in what they affectionately term ‘only good shit,’ which to the casual observer looks like thrashed, dirty, worn out, and sometimes extremely mangled garments. The clothes show their age through dirt, fading, stains, and holes, the type of damage that in most contexts, including other venues for vintage, would make them non-saleable or at least deeply discounted. Not here. Distressed Fest is a celebration of entropy.

The show skews younger, both buyers and dealers are mostly twenty-somethings, which is refreshing for those used to seeing the same old guard of familiar faces, and it also offers a different feel. Lange, who personally avoids the manic rush of competitive energy that characterises most vintage events, sees this as partly organic and partly intentional, and notes that the appeal of these items is ultimately more subjective, less in line with market standards, and therefore demands more reflective consideration. The biggest reason for why the vibe is different is because of the material itself – distressed and dirty clothes demand a different kind of looking and challenge established systems of value and taste, and not just within the vintage clothing market.

Cultural anthropologist Grant McCracken wrote how patina – the physical changes visible over the passage of time (oxidation, wear, surface sheen) – interconnected with how material culture conveys status messages. Physical property exists as symbolic property, and in the elite spaces McCracken describes presence of patina serves as evidence of established social status, a family that has passed on its silver plate over enough generations to see it tarnished and worn can claim longevity and established stature over a family that only just purchased it new. Patina is, essentially, material evidence of old money’s authority. He goes on to say that the explosion of fashionable consumer goods enabled by industrialisation diminished some of patina’s symbolic power, but didn’t eliminate it completely.1

How does this relate to sweat-stained undershirts? The stains, holes, and frayed cotton are signs of longevity that legitimise the age of the item, but things diverge from McCracken when we consider the nature of the garment itself – a cheap, ordinary thing, never intended to signal status, never worn by anyone of note, escaped landfill purely by chance. Dirty and damaged everyday clothes from the past do not speak to legacies of refinement, no thought was taken to carefully preserve them for future generations. They are outcasts, not relics, and persist in spite of their history rather than because of it. To wear them calls into question what parts of the past are worth preserving, and how we come to know and experience them. It’s also an aesthetic choice. Lange, who has a background in the antiques business and studied art history, explains his own connection to it: ‘part of what I like with distressed stuff, I could see the equivalences in other categories of things. Like with furniture, if it’s too beat up it’s not valuable, but there are also nicely worn brown leather club chairs and rugs that aren’t destroyed but might give an English cottage shabby-chic feel and even guitars, worn-in acoustics, sometimes people thing they play better but there’s also relic’d guitars where the paint worn out makes it worth more. So, it’s the ability to see this as an equivalent in clothes.’2 The parallels are all there, but there’s still something about dirty clothes that feels more unsettling.

Fashion, the champion of the new, has a fraught relationship with dirt. Generations of designers have played with the idea and material effects of dirt and decay. Vivienne Westwood took inspiration from punk kids in the 1970s to craft mohair sweaters that looked like they were disintegrating. Yohji Yamamoto famously quipped ‘there is nothing so boring as a neat and tidy look,’3 and Martin Margiela cultivated bacteria and mould on garments in 1997.4 Presently, pre-distressed jeans are so commonplace it’s unremarkable and even sneakers, normally prized for freshness, have been given the ersatz trashed treatment by Golden Goose and Gucci. Scholar Alla Eizenberg affirms that dirt is indeed fashionable nowadays, and coined the term ‘fashioned dirt’ to describe it.5 While fashioned dirt may not be new, it can still provoke disgust or irritation over the perceived inauthenticity of artful, strategically placed soil and wear for sale at top prices. This affront is, of course, an intentional part of the story, and one that’s significant enough to be the subject of the upcoming exhibition Dirty Looks at London’s Barbican Centre next fall.6 As effective as these design examples might be, ultimately, fashioned dirt is not real dirt.

Real dirt is not so easily styled. Dirty clothes, and their connection to the body, offers an extra level of discomfort. Cultural anthropologist Mary Douglas famously described dirt as ‘matter out of place’ and showed how the stigma and shame around it is informed by understandings of the hygienic and the aesthetic that are entrenched in morality. Dirt can be a marker of poverty, neglect, or lack of refinement.7 Dirt is also matter out of time, it marked a surface, a textile, at some past moment. It’s disruptive; not part of the design, and stands out in a way that was never intended. Much of the discourse around vintage leans towards, if not outright nostalgia, then an investment in a Benjaminian ‘aura’ connected to memories, real or imagined, of past times and the people who embodied the clothes. Dirt interrupts this romanticism like a record scratch. But the clothes at Distressed Fest can elicit connection in other ways. The element of individuality and chance is part of the appeal. As vintage clothes become more accessible through a range of curated digital platforms, hashtagged and organised by era, size, and style, the happenstance of stumbling across something unexpected is less likely. In terms of the vintage market, Lange sees the amount of dirt and damage also making difference, ‘it’s like on this curve – if [the garment] is in really good condition there’s value there, but also if it’s in aesthetically thrashed condition there’s value there… on either side there can be value.’8 As so often with style, the best examples can be found at the extremes.

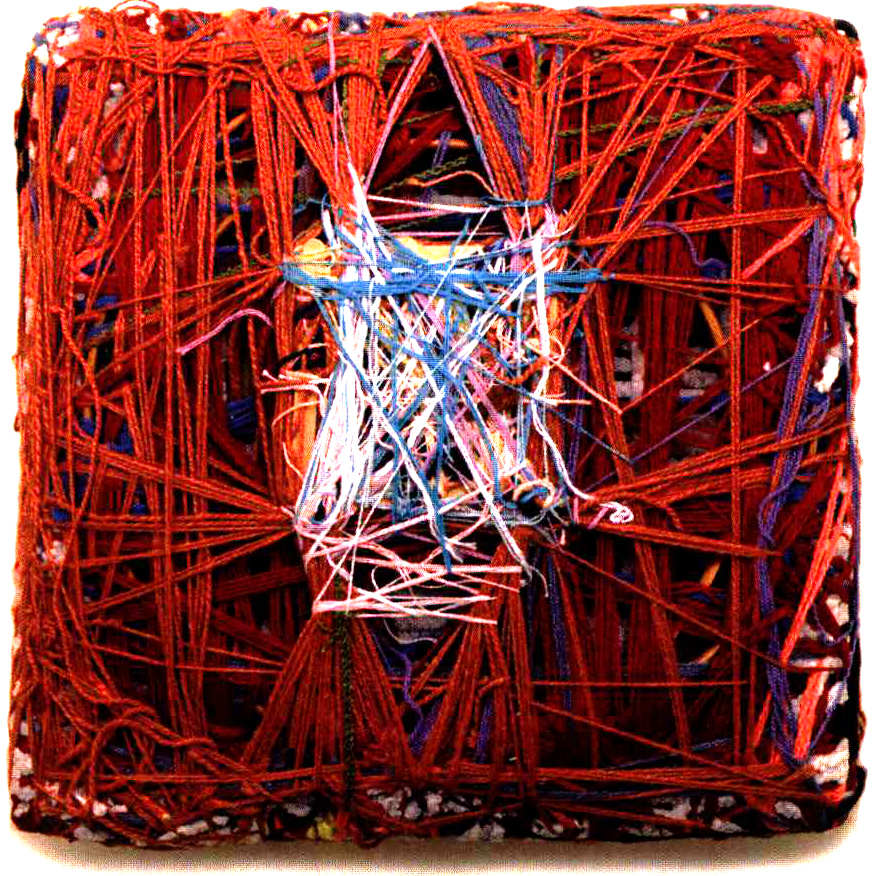

Dirt and decay aren’t typical selling points but part of the ethos of the show is about abandoning what’s typical and elevating distressed garments to wearable art. Wearable art, another nebulous category, is fitting if we consider how far removed these pieces are from their original state. Thanks to rough wear and the passage of time, they have become something else. Gressitt is known to borrow from the language of art as well, using ‘negative space’ to describe holes, for instance, which is becoming something of a trope for some in the vintage world.9 Lange sees the clothes sitting somewhere between folk art and fashion: ‘the wearable art for me it’s like, a lot of stuff that would be cool in folk art, like make-do’s where they would use materials outside the norm out of necessity, again there’s a social history there, and a lot of it just gets thrown away, and we’re normally so far removed from anything that gets repaired but I’m sometimes just attracted to the colour of a thing, the way it looks, I’ll put clothes up on my walls at home next to a painting. Some stuff is just pretty.’10 The fact that he counts several design teams including Balenciaga and Kim Jones among his clients and visitors to Distressed Fest suggests that he’s not the only one who feels that way.

Beyond the vintage market and designer fashion, museums sit at the pinnacle of discerning taste and care. It’s hard not to see Distressed Fest as the polar opposite of costume collections where historic clothing benefits from teams of professionals trained to prolong the life of the garment when it’s no longer embodied and living in the world. The aim, traditionally, is to exhibit the piece looking its best, as close to how it would have appeared in its time and faithful to the intentions that informed its making. Sarah Scaturro, the Eric and Jane Nord Chief Conservator at the Cleveland Museum of Art explains that: ‘the aesthetic mandates of display in fashion exhibitions were historically derived through methods of wardrobe maintenance and domesticity, which had overt moralistic tones. In early fashion museology, it was considered unseemly to show something wrinkled and dirty. Anne Buck, one of the first fashion curators, said: ‘It seems to me quite wrong to show garments in a ragged state, unless one is deliberately illustrating a slattern.’11 Things are, thankfully, progressing away from historical slut-shaming towards a more considered view of the reality of dirt and wear, and the stories it can tell. A few exhibitions, like the New York Historical and Smith college collection’s Real Clothes Real Lives: 200 Years of What Women Wore and the Met’s Sleeping Beauties have highlighted wear, damage, and repair in their narratives. Scaturro says that she ‘would support showing dirty or visibly worn garments if it facilitated story-telling, the curatorial narrative, and/or designer/wearer intent; if the dirt was historically significant (who determines that is a core question); and/or if stakeholders guided us to do so (who is identified as a stakeholder is another core question). What might be shown at your local historical society or a history museum might not be shown at the Costume Institute.’12 As ever, the situation is subjective, case specific, and worthiness is in the eye of the beholder, or in the institution. Still, it’s encouraging that more expansive thinking around distressed or dirty garments and the stories they tell might be welcomed in the future.

It’s too soon to say whether the market for dirty, thrashed clothes is going remain but for now, in an over-saturated, jaded, and largely digital landscape it’s doing a lot of the work that makes fashion exciting- provoking enthusiasm, eye rolls, and disgust in equal measure. In 1971, Alexa Davis summed up the appeal of vintage succinctly in the counterculture magazine Rags: ‘Old clothes have a way of horrifying the people you want to horrify while delighting the people you want to delight.’13 Distressed Fest does exactly this. Whether it’s seen as a sartorial statement or a kind of fashion trolling, it’s undeniably sustainable, and not just giving new life to old things but effectively keeping them on a kind of life-support in a world that would otherwise discard them.

Dr. Sonya Abrego is a New York City based design historian specialising in American fashion. She takes an interdisciplinary approach to examining the interconnections between popular culture, art, craft, and design. She’s the curator of Crafting Denim (2023), an exhibition for the Center for Craft in Asheville North Carolina, and her book, Westernwear: Postwar American Fashion and Culture (2022) is available from Bloomsbury.

Grant McCracken, 1988. ‘Ever Dearer in Our Thoughts: patina and the representation of status before and after the eighteenth century,’ In Culture and Consumption: new approaches to the symbolic character of consumer goods and activities. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ↩

Author Interview, 05/05/2025 ↩

Osman Ahmed, “An Oral History of Yohji Yamamoto,” i-D, September 6, 2022 https://i-d.co/article/yohji-yamamoto-ultra-issue-cover/ ↩

Anna Roos Van Wijngaarden, ‘Bacterial Stunts and Mold at Margiela – From 1997 til today’ Lampoon, March 26, 2024. https://lampoonmagazine.com/article/2024/03/26/martin-margiela-moldy-fashion-john-galliano-1997-technique/ ↩

Alla Eizenberg, 2025. “Fashioning Dirt: Opening a New Discourse.” Fashion Theory, March, 1–27. doi:10.1080/1362704X.2025.2481671. ↩

https://www.barbican.org.uk/whats-on/2025/event/dirty-looks ↩

Mary Douglas, Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo, Taylor & Francis Group, 2002, p.50 ↩

Author Interview, 05/05/2025 ↩

Connor Gressitt, (@legarbaage) 2025. ‘An idea I would love to talk about is negative space’ Instagram, February 26 2025, https://www.instagram.com/p/DGjAaGOSPm4/ and (@bidstitch) 2025. ‘Does negative space make it worth more?’ Instagram, May 1, 2025, https://www.instagram.com/p/DJHzaljuvDY/?hl=en ↩

Author Interview, 05/05/2025 ↩

Sarah Scaturro, email message to author, 05/04/2025, Anne Buck, ‘Costume in the Museum’ a lecture given to the Museum Assistants Group in Norwich, May 1949. Manchester Art Galleries, Platt Hall Archives, Anne Buck, Unlabeled box, folder ‘Anne Buck 1939 Lectures.’ p. 8. ↩

Sarah Scaturro, email message to author, 05/04/2025 ↩

Alexa Davis, ‘Old Clothes: Never Trust Anything Under Thirty,’ Rags, issue 8, January 1971, p. 43. ↩