Vestoj and Style Zeitgeist have teamed up in a dialogue and series of critiques of recent events in fashion media to raise more wide-reaching questions about the state of contemporary fashion media – and what that says about our industry at large. In the third instalment, we examine the notion of transparency, and how four different publishing platforms are dealing with the issue in relation to their respective funding models.

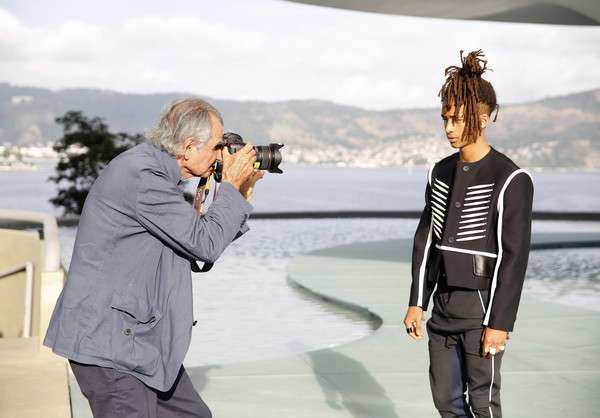

LOUIS VUITTON’S RECENT 2017 resort collection was presented last month at the Oscar Niemeyer-designed Niterói Contemporary Art Museum in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The modernist building’s curvaceous ramp, set against a spectacular mountainous bay, was an ambitious venue that made for a photogenic catwalk locale, though its opulence, for some, jarred with the country’s current political and economic uncertainty.

Coverage delivered in the form of reviews and photo-ops ensured that the cost of its staging – from the elaborate set, to the flying in of overseas press, buyers and celebrities – was money well spent. This came via the typical set of high traffic fashion platforms like Vogue.com, T Magazine, High Snobiety and WWD, ensuring the event was thoroughly and successfully documented.

Within this slew of articles, The Business of Fashion weighed in with a piece that recorded the event by mostly addressing its economic and political significance. Against a backdrop of the otherwise mostly frivolous coverage, BoF attempted a more analytical, and much welcome, perspective of the event. However, more thought provoking was a short statement at the end of the article stating LVMH’s investment in the platform. It read:

‘Disclosure: LVMH, which owns Louis Vuitton, is part of a group of investors who, together, hold a minority interest in The Business of Fashion. All investors have signed shareholder’s documentation guaranteeing BoF’s complete editorial independence. Lauren Sherman travelled to Rio de Janeiro as a guest of Louis Vuitton.’

The statement appears to be an attempt to reassure readers of the publisher’s candour, and their dedication to deliver unbiased and reliable coverage of the event despite the apparent relationship between host and guest. The gesture reflected a transparency rarely seen in the murky realm of fashion publishing.

Other publications have not gone so far as this. The fashion and lifestyle platform Nowness,1 that has Dazed & Confused’s Jefferson Hack as creative director, is also funded by LVMH. Though editorially very different to The Business of Fashion, there is no mention of the funding from the luxury group anywhere on the site. Instead, this information is found only through a general internet search, or on the LVMH website.2

‘Nowness has built the influence and authority to genuinely curate and shape the future of cultural conversations, and goes beyond just delivering experiences. We provide solutions to the industry by creating bespoke content for premium brands looking to reach our premium audience. Nowness is truly an innovator.’

– Jefferson Hack, creative director at Nowness, as featured on lvmh.com

When Nowness was launched in 2010, an article by The Guardian responded with a brief, but apt blog post shortly after, highlighting the project as one that, ‘promises to blur the lines between editorial and promotional content in a “beautiful” way.’3 Back then Nowness was one of the first of its kind in the digital realm, but the site has since become emblematic in the landscape of fashion publishing where sponsorships are often shadowy terrain, particularly concerning the agenda an investor might have. Though the funding model adopted by Nowness allows the platform to remain advertising-free, issues arise around selectivity and what is chosen to be featured as published content. For example, Nowness often releases exclusive features, such as collection videos, made by Louis Vuitton and other brands within the LVMH group.

The Talks,4 an online interview platform created and funded by Rolex, reflects another editorial venture for a luxury company. The website aspires to cultural capital with editorial featuring interviews with high profile figures from art, film and fashion – similar to earlier incarnations like United Colors of Benetton’s Colors or Acne’s Acne Paper. Unlike Nowness, The Talks’ website reveals its economic framework immediately and explicitly with the Rolex logo on the right-hand of the website’s banner, relying on this separation with the editorial as a brand-building exercise for Rolex. Within the industry, marketers and press teams place significant emphasis on ‘content,’ a buzzword that is seen to be a critical mode of generating cultural capital, and thus sales, for a brand.

A similar and recent example of brand-generated editorial is the print publication Porter, the in-house fashion magazine launched by Net-a-Porter in 2015. Porter models itself off the tradition of the seasonal high fashion magazine, and, though it is obviously affiliated with the Net-a-Porter group, still targets the same audience as its competitors, and is thus challenged by notions of transparency in terms of the brands they choose to feature – or not feature – in their fashion stories.

The relationship between advertising (brand) and editorial (publication) in fashion has never been straightforward, as scholar Lynda Dyson contends, ‘Editorial is […] perhaps, the most valuable form of media content because it is perceived to be unbiased and believable. Its ‘‘purity’’ (precisely because it is not advertising) derives from its aura of authority and neutrality.’5 But this merging of brand and publication has profound implications. The reality facing these relationships as they explore the paradigm of editorial-as-brand extension, beyond the era of print sales, is the compromise on editorial selection process. Even in posting a disclaimer at the end of their review of the Vuitton show, one could argue that BoF still faces the same issue of what is not said in the article. Thus the challenge facing fashion journalism lies in what an editor, stylist or writer chooses to feature.

The implications of commercial ties needs to go beyond a statement tacked on at the end of an article since it will inevitably permeate the editorial decision-making of what is published and written. For example, BoF’s Vuitton show review featured extensive quotes from an interview with LVMH’s chief executive, Michael Burke, who justified the show as an economic strategy for the luxury conglomerate despite the controversial locale, allegedly motivated by ‘generat[ing] dedicated global media coverage and activate regional markets.’6 The article appeared to defend the cultural implications of the event by choosing to feature a largely one-sided argument with a representative from LVMH, and so was not able to generate debate on the topic. In this case, as with others, the potential for self-censorship on what is written, so as not to compromise their source of funding (LVMH), is, arguably, as powerful as the choice of garments featured on the pages of Porter. Since, in the case of BoF, ‘investors have signed shareholder’s documentation guaranteeing BoF’s complete editorial independence,’ a risk might be that this apparent transparency allows the publishers to ‘get away’ with more.

The editorial content housed by these publications becomes a point of contention in negotiating reliable and balanced coverage. Though BoF, The Talks and Porter (among other similar brand-affiliated editorial ventures) function differently in terms of publications and have different investment models, they embrace new modes of funding that tread thorny terrain in maintaining a clear boundary between advertising and unbiased journalism. The final disclaimer at the end of the BoF article presents a move in a new direction in terms of editorial transparency, however it raises deeper questions about selectivity within editorial content.

Laura Gardner is Vestoj’s former Online Editor and a writer in Melbourne.

https://www.nowness.com/ ↩

https://www.lvmh.com/houses/other-activities/nowness/ ↩

‘LVMH launches luxury online magazine Nowness,’ The Guardian blog, 27 February 2010, http://www.theguardian.com/media/pda/2010/feb/26/lvmh-luxury-online-magazine-nowness ↩

http://the-talks.com/ ↩

Dyson, L 2008, ‘Customer magazines: The rise of the “glossies” as brand extensions’, in T Holmes (ed), Mapping the magazine: Comparative studies in magazine journalism, Routledge, London. ↩

‘Vuitton Investing, Not Surfing, in Brazil’ by Imran Amed and Lauren Sherman for The Business of Fashion, May 29, 2016 ↩