‘Nearly every show attendee, from the front row to the standing section, now arrives with phone in hand and Instagram account primed […]. This is fashion in the age of Instagram, a heady era in which digital media is changing the way clothes are presented and even the way they are designed. As shows are calibrated to be socially shared experiences, and fashion itself is rejiggered to catch eyes on a two-dimensional screen, some skeptics wonder what is being lost or sacrificed as fashion becomes grist for the digital mill.’

Matthew Schneider, ‘Fashion in the Age of Instagram’ for The New York Times, 2014.1

THE DIGITAL SCREEN AND fashion form the cornerstones of modern day consumer culture. Now the two are increasingly fused, but back in 2009, Alexander McQueen was one of the first designers to capitalise on this. The designer brought his creations into the digital sphere by live-streaming the apocalyptic, sea creature-inspired spring/summer 2010 vision, ‘Plato’s Atlantis’, on SHOWstudio.com. Only three years later, Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garçons proclaimed, ‘The future’s in two dimensions’2) and sent a collection of graphic, felt-pressed garments down the runway. Many saw the collection as a criticism of online media coverage of fashion, others saw it as embracing these technologies by literally making the designs flat. It begs the question: in a world of so-called ‘bi-dimensional fashion’3 and online oversharing, has creativity become the ultimate commodity?

Some would argue that the proliferation of mobile devices in the fashion industry has created a more open and participatory platform, evolving from a tradition of exclusivity. This echoes what theorist Martin Hand outlines in his essay ‘Images and Information in Cultures of Consumption’ in The Handbook of Visual Culture. He argues that ‘The image has simultaneously become the vehicle, context, content and commodity in consumer culture’. Hand goes on to explain that there is ‘an increasingly commodified yet participatory culture’4 evolving out of online social media sharing platforms such as Twitter, Vine and Instagram. Fashion shows may still be restricted to only a limited number of journalists, bloggers and photographers, however social media enables all aforementioned participants to share the event with a much wider audience. Cara Delevingne’s live runway video from the Giles autumn/winter 2014 ready-to-wear show garnered over 230,000 likes from her 5,828,643 followers,5 the result of combining celebrity status, brand power and the allure of the spectacle.

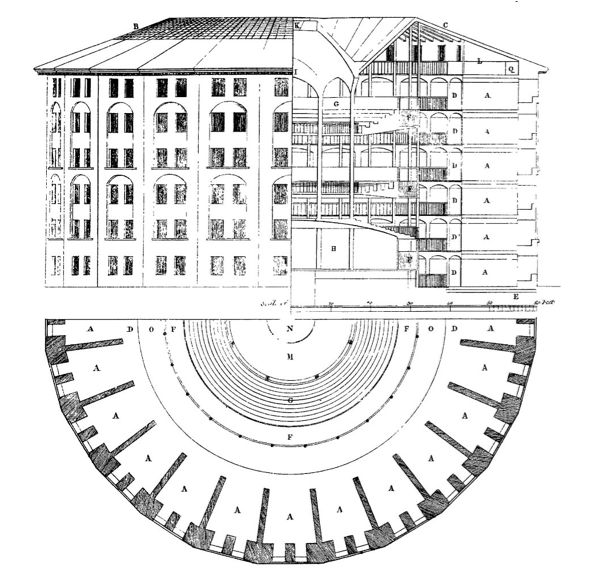

Whilst some might see the use of mobile devices as scratching away at the fashion industry’s inaccessible and glossy exterior, it also provides an interesting model for Michel Foucault’s theory of simultaneous surveillance and self-surveillance as proposed through the Panopticon. The theorist outlines in his 1975 book, Discipline and Punish, that those in a field of visibility assume the responsibility of being observed. Analysing this architectural structure, where a subject is under constant surveillance, Foucault concludes that ‘the major effect of the Panopticon: to induce in the inmate a state of conscious and permanent visibility that assures the automatic functioning of power.’6 This emerges with Facebook, Twitter and Instagram as its twenty-first century reincarnations, which have induced a sense of constant surveillance for activities within the fashion industry.

Continuing this notion, in her piece ‘How Instagram Can Make You Forget Why You Love Fashion’ for i-D magazine, fashion journalist Courtney Iseman states: ‘The entire industry has adapted to the fact that now it’s not just a few select journalists writing about shows in their columns, but the masses click-click-clicking away on their smart phones to share their take on the shows and the clothes with their thousands of followers’.7 This instantaneous documentation of the fashion show means that audience members experience the garments not in their three-dimensional state, but are instead transfixed by the two-dimensional vision of what they are looking at on their mobile screens. Furthermore, the social media coverage of the ‘circus’ surrounding fashion, which now includes celebrity sightings and street style, in some cases becomes more prioritised than the fashion being presented.

Beyond the catwalk, professional photographers and image-makers are also fully embracing the mobile medium. Nick Knight’s pioneering online platform, SHOWstudio, showcases projects such as the ‘#DIESELTRIBUTE’ campaign, ‘Pussycat, Pussycat’ (an Instagram photo shoot) and ‘The Elegant Universe’ (a couture photo shoot captured on an iPhone). The use of a smart-phone product as opposed to higher-quality photography equipment not only enmeshes the smartphone fashion image even more into the consumer culture cycle but further democratises the production method of the fashion images by professionals and members of the public alike.

Alongside Knight and Delevingne, many other fashion platforms and practitioners have embraced the popular medium of the smartphone as a press and marketing strategy. For instance, Centrefold, a biannual arts and fashion magazine, was hired by Nokia to create an issue that was shot entirely on one of the brand’s latest mobile devices. The designer Kenneth Cole, who staged his runway comeback after seven years absence, sent models down the runway with mobile phones taking pictures of the audience during the finale, an act that echoed Foucault by reversing the viewer/participant roles. For, according to Foucault, ‘the Panopticon is a machine for dissociating the see/being seen dyad: in the peripheric ring, one is totally seen, without ever seeing; in the central tower, one sees everything without ever being seen.’8

Although these image-making processes can be deemed as democratic and accessible, the ever-quickening pace of consumer commodities only gains momentum through the constant influx of different ‘It’ people, labels and objects being generated through online platforms. While fashion has always had an obsession with the new, these digital additions are sending the cycle into overdrive. Certain designers like Phoebe Philo have consequently banned photography at their shows as an attempt to keep a certain aspect of the fashion industry sacred in the age of overexposure.

The examples of Cara Delevingne and Nick Knight also raise issues on authority and status in fashion. It takes a photographer with Knight’s credibility to shoot an international campaign on an iPhone. Likewise, only someone with the following of Delevingne could post a runway selfie video that goes viral. The influx of smartphones and online social media may make the general public feel like the velvet rope to enter the fashion macrocosm has been set aside, however in reality the boundaries between insiders and outsiders are still very much in place.

Carla Seipp is a freelance fashion, arts and fragrance journalist.

‘Fashion in the Age of Instagram’ by Matthew Schneider for The New York Times, April 9, 2014. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/10/fashion/fashion-in-the-age-of-instagram.html?_r=0 ↩

‘Comme des Garçons Fall 2012 Ready-to-Wear Collection: Runway Review’ by Tim Blanks for style.com, March 2,2012. http://www.style.com/fashionshows/review/F2012RTW-CMMEGRNS ↩

‘Fashion in the Age of Instagram’ by Matthew Schneier for NYTimes.com, April 9, 2014. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/10/fashion/fashion-in-the-age-of-instagram.html?_r=0 ↩

M. Hand, ‘Images and Information in Cultures of Consumption’ in The Handbook of Visual Culture, edited by I. Heywood and B. Sandywell, Berg, London & New York, 2012, p. 526 ↩

http://instagram.com/p/kh0kmODKBX/ ↩

M. Foucault, ‘Discipline and Punish, Panopticism.’ In Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison, edited by Alan Sheridan, Vintage Books, New York: Vintage Books, 1977, p. 197. ↩

‘How Instagram Can Make You Forget Why You Love Fashion’ by Courtney Iseman for i-D Magazine, July 14, 2014. http://i-d.vice.com/en_gb/read/think-pieces/3653/is-the-fashion-worlds-instagram-feed-getting-you-down ↩

M. Foucault, ‘Discipline and Punish, Panopticism.’ In Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison, edited by Alan Sheridan, Vintage Books, New York: Vintage Books, 1977, p. 201-202 ↩