But what is remarkable about this image-system constituted with desire as its goal […] is that its substance is essentially intelligible. It is not the object but the name that creates desire; it is not the dream but the meaning that sells.

From Roland Barthes, The Fashion System. 1

THE MAIN SIMILARITY BETWEEN fashion and fragrance seems simple enough: we wear both on our bodies. However, there are more complex coinciding structures within these decorative matters of the human flesh at second glance. Beginning with Coco Chanel’s eponymous ‘No. 5’ fragrance to the more recent trend of celebrity fragrances, the following series considers the correlations between the consumer industries and ideologies behind clothing and perfume.

Fashion, advertising and fragrance exist to sell us a vision, conjured up in the mind of a designer, creative director or perfumer in order to be translated, concocted and packaged into material form. ‘Chanel No. 5’, the creation of perfumer Ernest Beaux and the first scent to incorporate the synthetic ingredient aldehyde, perhaps stands out as a primordial collision in this world of fashion, marketing and fragrance. As Barthes notes, names matter, for would the same scent have had everlasting appeal if it were named Topshop No. 6? Probably not. In reality, the houses of Lucile and Poiret had been selling their own in-house fragrances and ‘Parfums de Rosine’ lines over ten years prior to No. 5’s release in 1921. Historical nitpicking aside, how can a brand that sells a physical product – like garments – incarnate itself into something as fleeting and immaterial as a scent?

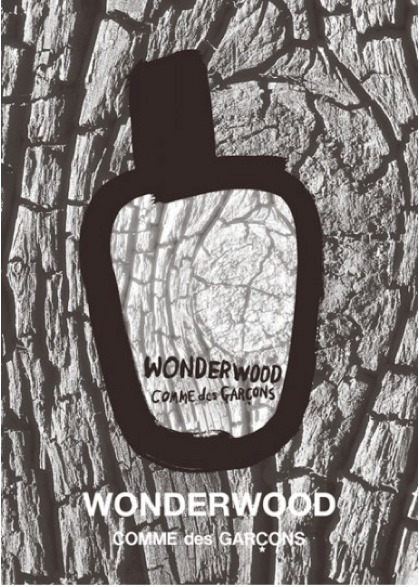

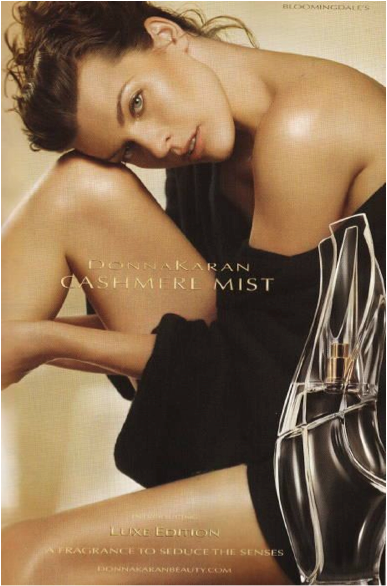

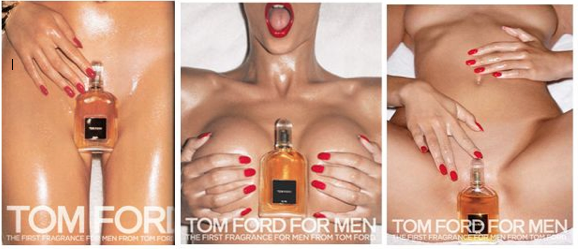

The success of a fashion brand in fragrance requires a concise visual, olfactorial and tactile message. For example, by showing an abstract illustration of the perfume bottle (rather than a realistic depiction), the advertising campaign for ‘Wonderwood’ successfully conveys the scent’s smoky, woody and mysterious incense notes. This is suggested not only through its name, but also a grey colour palette, an abstract representation and a tree bark close-up. For ‘Wonderwood’ Comme des Garçons sticks to its unpredictable, tongue-in-cheek approach, utilising everything from the scents of flaming rock and nail polish in ‘Odeur 53’ to highly sculptural packaging. The Comme des Garçons campaigns tend to showcase the product and nothing but the product, whereas other more traditional fashion brands take a more direct approach. After all, what better extension of one’s brand than to scent the skin which you are dressing? Three fragrances to consider for this example are Donna Karan ‘Cashmere Mist Luxe’ (a woody, white floral scent with notes of ylang-ylang, jasmine, and suede), the bestseller Dolce & Gabbana ‘Light Blue’ (a citrus floral eau de toilette formula with lime and cedar accents) and ‘Tom Ford for Men’ (a tobacco leaf and ginger musk fragrance).

In the chapter ‘The Advertising Message’ from his book The Semiotic Challenge, Roland Barthes explains that the language of advertising operates on two linked levels: ‘the encounter of a level of expression (or signifier) and a level of content (of signified).’2 So as a viewer we are confronted with an actual product (the perfume) and a visual representation of the product through the image, which is the powerful tool used to sell. ‘Hence we are here confronted with a veritable architecture of messages (and not a simple addition or succession) itself constituted by an encounter of signifiers and signifieds […]’3 Although Barthes was referring to the written language of advertising, these theories can also be applied to its visual aspects, and used to help interpret the messages that fashion brands convey through their fragrance releases.

Simply put, the layers making up each fragrance advertisement above are the product itself, its relation to the human body, the overall image itself, and its branding implications. The fluid packaging form of ‘Cashmere Mist’ is echoed by the soft posing and the garments of the model, the perfectly sculpted, bronzed bodies of the ‘Light Blue’ couple are placed next to the ‘his’ and ‘hers’ version of the fragrance, and in the ‘Tom Ford for Men’ advertisements, the perfume bottle stands in as a phallic representation of a male partner, cradled in between his lover’s thighs and breasts.

All of these images also incorporate texture into their message, for just as fashion historian and curator Maggie Murray notes in her book, Changing Styles in Fashion, ‘textiles are the springboard of fashion: the sibilant hiss of silk, the crisp, dry rustle of taffeta, the luxe of pure woollens with their soft, sometimes buttery, hand and the unbridled crump of our cottons and linens all speak to us’4, so too does a scent imply its own texture – be it the golden warmth of ‘Cashmere Mist’, the crisp lightweight feel of ‘Light Blue’ or the sweat-drenched sensuality of ‘Tom Ford for Men’. In a branding context, Donna Karan’s ‘Cashmere Mist’ wraps itself around the body in a cozy yet chic manner akin to her womenswear creations; Dolce & Gabbana ‘Light Blue’ gives us a glimpse into their lifestyle of dolce vita summers and Tom Ford appeals to our most primal instincts with a visual message of pure sex. Through their merchandising of scent, tactility and sight, fashion designers give us the allusion that our choice of feminine elegance, vacations in Italy or steamy encounters is seemingly only a purchase (and a spritz) away.

Carla Seipp is a freelance fashion, arts and fragrance journalist.

R. Barthes, ‘The Fashion System’, Hill and Wang, USA, 1983, p. xii ↩

R. Barthes, ‘The Advertising Message’. In: The Semiotic Challenge, translated by Richard Howard, University of California Press, USA, 1994, p. 173 ↩

R. Barthes, ‘The Advertising Message’. In: The Semiotic Challenge, translated by Richard Howard, University of California Press, USA, 1994, p. 175 ↩

M. Murray, ‘Changing Styles in Fashion: Who, What, Why’, Fairchild Publications, London, 1990, p. 221 ↩