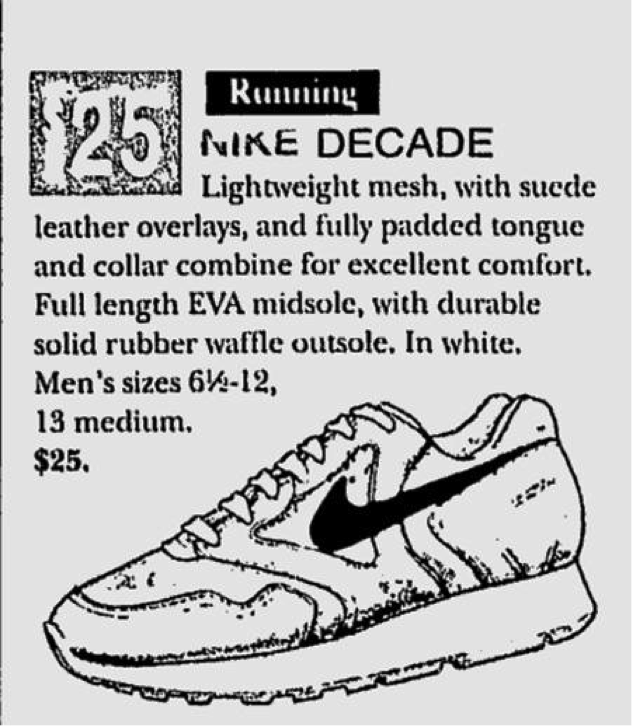

IN MARCH 1997 THIRTY-NINE people were found dead in a mansion in Rancho Santa Fe, California, an upscale suburb of San Diego. Between the night of the twenty-second and twenty-third, they took their lives in shifts, each group tidying up after the previous. First they drank a poisonous cocktail of barbiturates, vodka and applesauce; then they proceeded to tie plastic bags over their heads. The bodies were found lying on their backs with purple shrouds covering their faces, dressed in all-black uniforms and brand new Nike trainers. The uniform-like clothing made it impossible to distinguish between male and female bodies. In fact, it indicated that the body’s physical traits were perhaps irrelevant or undesirable. Five dollar bills and change were found in the shirt pockets, alongside identification. Next to them were rucksacks and bags with a change of clothes. The careful planning suggested that the act was of a ritual nature; a farewell videotape confirmed that the bodies belonged to members of a millennial religious cult known as Heaven’s Gate. But it was the sartorial choices of the group, however macabre, that would become a trademark with cultural permanence beyond the event itself.

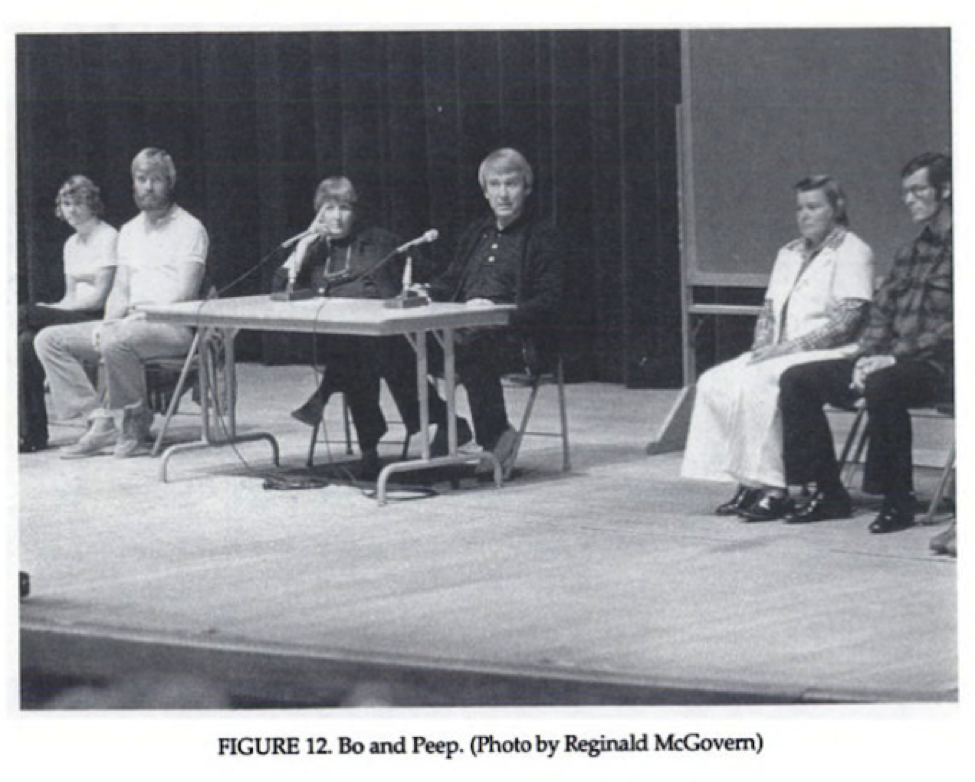

Heaven’s Gate was just the latest incarnation of a spiritual New Age movement created in the mid 1970s by Marshall Herff Applewhite and Bonnie Lu Nettles, later known as Do and Ti, or Bo and Peep, respectively. The two first met at a hospital where Applewhite went to seek treatment for his sexual and psychological issues. A successful academic with a wife and two children, Applewhite was a closeted homosexual. Deeply troubled, he obtained a divorce and was fired by St. Thomas University for having an affair with a student. Thought he didn’t find the ‘cure’ he was looking for at the hospital, he instead found an inseparable companion in Nettles. They first operated a metaphysical centre in Oregon and then led a semi-nomadic life for years, gathering followers and refining their ideology by merging New Age spirituality and elements from Christian theology with a belief in intelligent extraterrestrial life rooted in Gnosticism as well as popular culture. What tied these elements together, perhaps unsurprisingly considering Applewhite’s problematic relationship with his sexuality, was a stark refusal of the body. Fleshy, terrestrial life was looked at with disdain, in contrast to the extraterrestrial ascension that awaited the group members. After Nettles died of cancer in 1985, the urgency to reunite with her spirit on the spacecraft probably strengthened Applewhite’s belief in an exclusively spiritual afterlife, cementing the idea of the human body as mere ‘container’ in the group’s theology.1

As in most religions, detachment from the body was achieved through bodily and sartorial practices. These included identical diets, grooming – all members sported a buzz cut – and clothing, which were meant to reinforce a unified group mentality. Heaven’s Gate’s uniforms changed slightly over time, but were consistently unisex and monochromatic: early images of Applewhite and Nettles show them wearing all black, while in a 1992 promotional video series all members wore grey collarless shirts. The dress code was to ‘emphasise modesty, comfort and utilitarian value’ while also reorienting the members ‘toward the Next Level,’2 the group’s term for their extraterrestrial afterlife. Heaven’s Gate’s image for the ‘Gray,’ the alien species that were supposed to grant them access to their next life, was indeed represented as a bald, gender-neutral being dressed in a skin-tight, silver uniform. But cult members did not limit themselves to the adoption of clothing that concealed gender markers. In fact, after Nettle’s death, Applewhite encouraged them to view their human bodies themselves as garments:

‘We use the reference [“of vehicle”] to this body that we’re wearing – this flesh and bones – we use the term “vehicle” because it helps us separate from the body […] This is just a suit of clothes that I’m wearing, and at times it can be an encumbrance for me. It can be something I don’t want to identify with.’3

This belief partly explains why some male adepts went so far as to undergo castration in an attempt to eliminate the urges of the flesh. It probably also made the 1997 ritual suicide, or ‘graduation’ in Heaven’s Gate’s terminology, more acceptable for the group. All members seemed indeed relieved at the idea of leaving their containers behind. However, the media coverage of the event reveals a widespread scepticism towards the group’s religious ideology and a quasi-morbid fascination with the appearance of its members, in particular with their ‘graduation’ uniforms. One article reports a neighbour saying that ‘they looked like computer nerds,’ with the journalist adding that ‘they resemble no one quite as much as the early American Puritans in their plainness.’4 A different reporter called them ‘cybermonks and nuns who all dressed in black and wore their hair close-cropped,’5 while a journalist writing for the Los Angeles edition of Daily News suggested that they embodied ‘the wealthy casualness of modern geek chic’ and mimicked a celebrity journalist by observing, ‘And those all-black uniforms? As we saw at the Academy Awards last week, same-color shirts, ties and pants are hot, hot, hot this season.’6

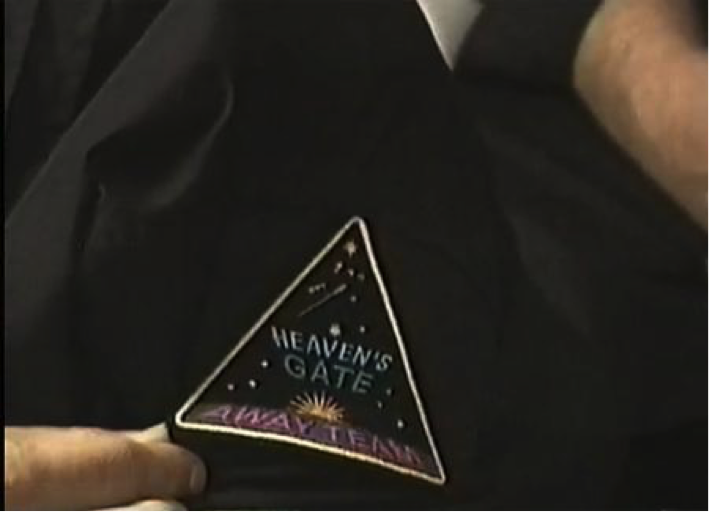

The ties of the group with popular culture were indeed strong. Many members used to be avid fans of The X-Files, Star Wars and Star Trek – Heaven’s Gate’s black shirts featured Away Team badges, a reference to captain Kirk’s exploration team. These phenomena resonated ‘with gnostic myths of ascension’ and occasionally drew from ‘prophecies of millennial doom,’ as Star Wars creator George Lucas’ keen interest in the work of Gnosticism scholar Joseph Campbell suggests.7 As noted by many a reporter, Heaven’s Gate members also dwelled in California’s burgeoning tech culture: the group enjoyed a comfortable lifestyle thanks to their website design firm, unironically called Higher Source Contract Enterprises. While living in almost total isolation, then, the affiliates were very much in touch with 1990s American culture. In fact, the group’s ideology was a direct product of the ongoing merging of popular culture, spirituality and consumerism in the United States at the time.

In particular, it was the Nike trainers worn for the ritual suicide in 1997 that managed to capture the collective imagination in popular culture. As a brand which enjoyed cult status – pun intended – Nike’s signature swoosh was one of the most recognised logos all over the world. A 1998 article reports that, according to a research conducted by the company, its logo was recognised by 97% of Americans and that each American spent an average of $20 a year on Nike products.8 However, because the brand was so easily identified, its reputation was more readily subject to bad publicity. Between 1997 and 1998 Nike shoes were spotted on the Heaven’s Gate members, and on one of the victims of a school shooting that took place in Oregon in May 1998. A Nike baseball cap was also regularly worn by felon O.J. Simpson, a brand ambassador not as desirable as Michael Jordan, who at the time had signed a multi-million dollar deal with the company.

The swoosh became so ubiquitous, and the company so profitable, that satirist Will Durst imagined a meeting at Nike headquarters in which marketing executives discussed how to capitalise on the Heaven’s Gate ritual suicide:

‘Nike is still holding damage-control meetings on focus-group surveys to figure out if that whole Heaven’s Gate thing was good publicity or bad. “Well, on the one hand, the swoosh was on the cover of everything. On the other hand, it did tend to put a reverse spin on the whole ‘Just Do It’ thing. What we need to do is find the new cults. Quietly. Emerging cults. Cutting-edge cults. Post-grunge cults … And figure out a way where they don’t die in the end.”’9

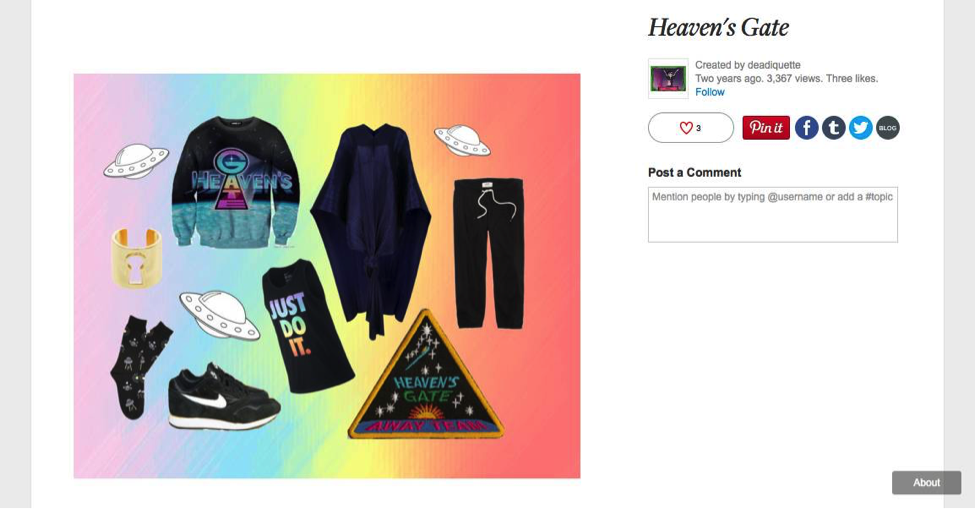

In a twisted turn of events, time proved Durst right. The cult of Heaven’s Gate has entered commodity culture courtesy of 1990s nostalgia. Only two years after the mass suicide, objects that belonged to the affiliates were auctioned off by county officials in San Diego, including clothing and Nike trainers. Memorabilia were bought by ex members, by the curator of the Museum of Death in Los Angeles as well as by ordinary people – some hoping to up-sell them on the internet as ‘there are some weird people out there.’10 Internet in particular has contributed to the cult’s popularity in recent years. One need not adventure in its deepest recesses to find Heaven’s Gate Away Team patches and t-shirts available for purchase, or to stumble across Creators and Destroyers, a brand created by a religious cult aficionado that offers a ‘cult starter’s pack,’ Heaven’s Gate DVDs and Applewhite posters. A user on Yahoo-owned fashion site Polyvore even made achieving the Heaven’s Gate look much easier thanks to their style board, which of course includes a Nike top with the famous ‘Just Do It’ slogan. Durst’s parodic scenario suddenly does not seem so far-fetched.

In his seminal text Modernity At Large, anthropologist Arjun Appadurai observes that nostalgia is an essential element of modern merchandising and marketing. Specifically, he discusses the notion of ‘ersatz’ or ‘armchair nostalgia’, which he defines as ‘nostalgia without lived experience or collective historical memory.’11 Following this reasoning, symbols that once held powerful meanings are consumed as empty signs or simulacra; this is true for Heaven’s Gate T-shirts as much as it is for the punk or grunge elements that are seasonally regurgitated on the runways.

What is ironic in this case is how a uniform intended to favour the wearer’s detachment from the body has been recontextualised as fashionable commodity – though perhaps not particularly surprising considering the popularity of 1990s-inspired normcore on runways and streets. The Heaven’s Gate look is, after all, a cult twist on the uniform of a suburban dad. The memory of Heaven’s Gate, then, paradoxically survives through the loss of its original meaning, and its very survival reflects the broader mechanisms of contemporary, especially American, culture. The cult has acquired its own niche spot, located somewhere between an MTV special, a Spice Girls doll and the umpteenth Friends re-run.

Alessandro Esculapio is a writer and PhD student at the University of Brighton, UK.

J.R. Lewis, “Legitimating Suicide: Heaven’s Gate and New Age Ideology,” in C. Partridge (ed.) UFO Religions, Florence, GB: Routledge, 2012, pp. 103-28. ↩

B.E. Zeller, Heaven’s Gate: America’s UFO Religion, New York: NYU Press, 2014, p. 142. ↩

Excerpt from the group’s 1991-2 satellite program, quoted in B.E. Zeller, Heaven’s Gate: America’s UFO Religion, New York, NYU Press, 2014, pp.118-9. ↩

R. Rodriguez, “Lost In Paradise: A Journey Through Heaven’s Gate,” Philadelphia Tribune, April 11, 1997. ↩

J. Carlin, “Who’s Next Through Heaven’s Gate?”, The Independent, March 30, 1997. ↩

G. Gaslin, “Cult of Popular Culture: Heaven’s Gate Suicide Earmarked With Mixed Bag of Media Iconography,” in Daily News, Los Angeles edition, April 2, 1997. ↩

C. Lehmann, “The Deep Roots of Heaven’s Gate,” Harper’s Magazine, June 1997, p. 15. ↩

T. Egan, “Downsizing the Swoosh: Nike’s Ubiquitous Logo Is Suffering From A Serious Case of Overexposure”, The Spectator, November 21, 1998. ↩

W. Durst, ‘Nike Knocking On Heaven’s Door,’ The Progressive, June 1997, p.12 ↩

One of the bidders quoted in “Suicide Cult’s Possessions Auctioned Off”, The New York Times, November 22, 1999. ↩

A. Appadurai, Modernity At Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization, Minneapolis, MINN.: University of Minnesota Press, 1996, p. 78. ↩