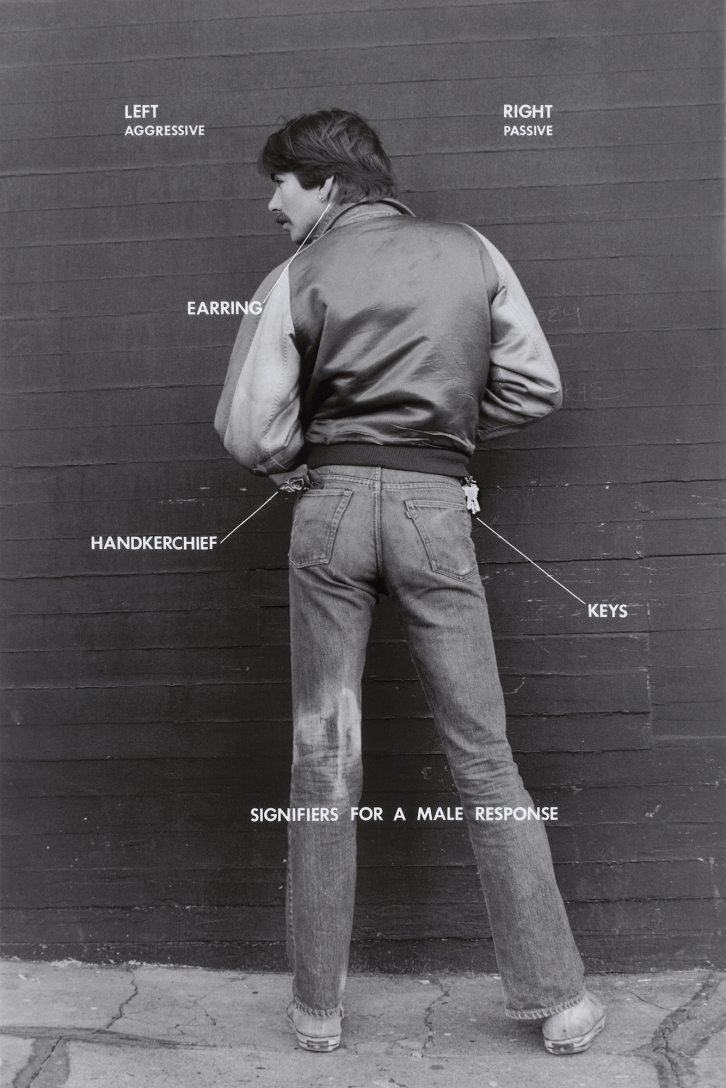

ALL THE COLOURS OF the rainbow; all the colours of the earth: years before Gilbert Baker designed the rainbow flag, the most recognised symbol of gender and sexual minorities, some were already flagging. Simple squares of woven, printed, cotton cloth, bandanas (aka hankies) were worn wrapped around biceps or tucked into the back pockets of denim or leather pants and even occasionally tied around a boot. These bandanas, their colours and placement, left side or right, became the key material element in a system of coded messages signalling an individual’s sexual proclivities, tastes and kinks: the ‘hanky code.’

Bandanas are traditionally used as neckwear or as headwear. They are protective, decorative, hygienic and concealing as well as signifying. Worn around the neck so that it can be quickly and easily pulled up around the mouth and nose, the bandana evokes cowboys, railroad engineers and miners. It is protective gear for blue-collar workers and middle-class outdoor enthusiasts. It can be worn wet or dry and is suitable for use as a low-tech particle filtration device in dry and dusty climates and dirty conditions. But it can also conceal identity, suggesting highwaymen, train robbers, revolutionaries, street artists, gangsters, and antifa – among others. Tied to a stick, it’s a romantically nostalgic suitcase for what were once called hobos.

Bandanas had a long history well before they were adopted as coding devices in the mid twentieth century. The etymology of the word ‘bandana’ runs through Persia and the Indian subcontinent. Bandhna means ‘to tie’ and bandhnu is ‘tie-dye’ in Hindi. Bandhana means a ‘bond’ in Sanskrit. This last association and the related bandhnati (‘he binds’) is easily reminiscent of the English word ‘bondage.’ (They could be cousins, but they’re not. ‘Bondage’ is from the Middle English ‘bond/a,’ via the Anglo-Latin ‘bondagium,’ meaning serf, one bound to the land. )

India produced the first recognisable bandanas; red or blue squares of cotton or silk, densely decorated with tiny white dots. Their simple design made them practical and adaptable. Then as now, they were used as headwear, neckwear, straps and packaging. Patterns evolved to become more elaborate, and teardrop-shaped motifs appeared. These were ‘buta’ or ‘boteh’ from the Persian: Zoroastrian symbols of eternity and life. They combine stylised elements of long-lived cypress trees and annually occurring floral sprays. Under Arab/Muslim conquest, and most likely in the Azerbaijani region, the motif curled further, becoming the ‘bent’ cedar, a hidden (coded) reference to the virtues of strength, resistance and modesty under occupation. This is the pattern most associated with bandanas and that which we recognise as ‘paisley’ today.

During the sixteenth century, buta patterned cloth, imported by the East India Company, became available in Europe. By 1640, Marseilles France had become a production for continentally produced fabric bearing the popular pattern. From ‘couvre-chef,’ meaning a head covering, comes ‘kerchief,’ which expands via location and use into ‘neckerchief’ and ‘handkerchief,’ the latter of which shortens to the familiar ‘hanky’ of the code. Across the English Channel in Scotland, Glasgow and the nearby town of Paisley became early British centres of manufacture and ‘paisley’ eventually became the generic term for the pattern.

Bandanas evoke the nineteenth-century American West, and contain a bit of the myth of it. Cowboys, train engineers, scouts, sailors, prospectors: hard-working, hard-drinking members of mostly male societies. In the absence of law, the ‘wild’ west operated, as certain contingently extralegal subcultures do still, on systems of codes of conduct, including for instance cowboy codes and road codes, standards of acceptable behaviour that while not mirroring polite or straight society, nevertheless provide a structure within which certain expectations can be conveyed. How is property marked? How are disagreements settled? What constituted an honourable duel? Who led and who followed (i.e. danced male and female parts) in all-male miners’ camps? Dancers would wear hankies tied to their right or left sleeves to signal respective roles. In the century and a half since, bandanas have become a standard of Western equestrian gear, including being a staple of every gay cowboy, whether urban or rural, circuit queen or rodeo circuit rider.

The ‘busy’ aesthetic of the traditional bandana allows for easy deep coding. Early twentieth-century advertisers experimented with festooning everyday mass-produced objects with logos, mottos, recognisable images and thematic characters. The age of mass reproduction of images was just gearing up. Clubs wanted insignia, businesses wanted give-aways, tourists wanted souvenirs, and consumers were starting to demand variety. Printed bandanas were small, inexpensive to produce in large quantities and easy to transport. With their square, flat, printable surfaces, they were ideal for the emerging practice of commercial branding. Bolstered by nostalgia for a west that never existed in reality as it did in depictions, popularity of the handy hanky among the general public soared.1

The twentieth century saw the bandana’s adaptation by motorcyclists, both straight and gay. They were especially popular with outlaw or 1%-er bikers, so self-named in joking contrast to the assertion that 99 percent of motorcycle riders were good, law-abiding citizens. Outlaws were less likely to have conventional jobs and more likely to have long hair than citizen bikers. Folded long and used as a headband, a bandana holds long hair down. Worn over the whole head and secured in back, it performs the same function as its stylistic and functional cousin, the do-rag. These styles arose in the days before helmet laws and before the multi-coloured bandanas of today’s code. There were two basic colours: red and blue.

The rise of the bandana as a coded accessory in gay circles can be seen in the context of the historical moment when it appeared. The bandana was already in subcultural use by the 1960s. Interest in ancient cultures and Eastern religions was in ascension and hippie trails through Central and South Asia were among the roads more travelled. Beat souvenirs spurred popularisation of the buta or paisley pattern. Acid tripping leant colour to the counterculture. In 1967 Fender issued a pink paisley guitar. Hippie-dicks, hair fairies, gay bikers, leathers and other ancient non-mainstream categories of queer folk populated the early history of gay liberation and contributed to its rise. The adaptation of coded flagging in leather sub-cultures arose in this moment. Without the commercial availability of a range of differently coloured bandanas, the hanky code itself would have been impossible.

In leather subcultures, the signifying factors of a bandana’s colour and placement are arguably the most remarkable. What does each colour mean worn left or right? That is the code. But use value still adheres and includes: use as a binding device (Bandhnati), as a blindfold, a gag or a strap to tie up genitals. The homoerotic bandana both says something and does something. Mostly it distinguishes. The late journalist and leather maven Robert Davolt noted:

We are leather, we label: Top, bottom, master, slave, daddy, boy, gay, straight, Mr., Ms, red hanky, blue. At some point, you are not inclusive if you try to claim these all (or none) at once, merely indecisive.2

There is some disagreement about the details of the establishment of the code. Certainly, red and blue bandanas had a long and fairly well established history both within and exterior to gay and leather subcultures. But it was informal, and had not yet been codified. The code is generally believed to have been ‘officially’ launched in 1972 by Alan Selby of Mr. S Leather and Ron Ernst and Pat O’Brien of Leather ‘n’ Things. They worked together at this time, developing many of the products that are today considered classics of leather style. This was when Mr. S was still based in London, well before there was a retail outlet in San Francisco. Selby described the circumstances that led up to the publication of an initial list of coded colours:

We had gotten an order in from a bandana company and they had inadvertently doubled their order. Since we’d just started doing business with them we didn’t want to return the order, so we had to think up a way of selling all these extra dozens of bandanas…the hanky code took off like a whirlwind and spread internationally…we worked together deciding which colours were going to represent what.3

Flagging is a way of communicating basic information without needing to speak. Bandanas are soft introductions. They are self-labelling devices, material imbued with meaning, intended to provide enough information for cruising parties to determine the likelihood of an erotic match. In many cases, they provide a way of making an initial connection. Like any system of underground communication, it is community specific, and does not travel well. Where do you wear them and what does that mean? Subcultural meaning stays local.

Alan Selby listed the original colours in his recounting of the circumstances in which the code came about, but there is good reason to consider that his memory was not entirely accurate. He recalled:

Despite arguments to the contrary, when worn on the left side you were recognised as a top, and right side, bottom. This was a universal recognition signal. There were about twelve colours to start with: red, black, navy blue, grey, orange, yellow, brown, green, purple, light blue…light blue was very popular!’4

Although Selby lists the colour purple as one of the original colours, it was in fact added a half dozen years later by Jim Ward, the founder of The Gauntlet, widely regarded as the founder of modern body piercing in the global west. Holes may be temporary or permanent, may barely break the skin, can hold meat-hooks thick enough to support a body’s suspended weight, might be invisible, or can even stretch out to sport massive jewelry and attract attention to the protuberances they pierce. The freak is a forest of holes and protuberances, and holey freaks flag purple. In Running the Gauntlet, Ward describes how purple became associated with piercing:

By 1978 I had made up my mind that purple was to be the colour for body piercing. This had sprung directly from another of those products of gay creativity, the bandana or hanky code…purple, the colour associated in astrology with prosperity and good fortune; purple, the colour draping Catholic and Anglican churches during Holy Week when they commemorate the day their deity got pierced.5

Red, together with blue, is one of the two original bandana colours. It reaches into time and across space. It travelled from the Indian subcontinent to the North American far west. The classic cowboy bandana was red. In the code it is the colour of handballers, or fist-fuckers, of the (mostly) men who reach up into others and those who take it that way. Alan Selby flagged green and gray – and red. Feel the heart beat: that’s red.

Orange was, and is, a problem colour. Worn on the left it means: ‘I’ll do anything, anytime – to you.’ Worn on the right it once mirrored a similar thinking from a bottom’s POV: ‘Do me. No limits.’ But of course there are always limits and nobody, top or bottom, is really available for anything anytime. So the right side re-coded and became some version of ‘nothing now.’ Flanked by impossibility on one side and pointlessness on the other, orange is the red-headed stepchild of the code. People laugh at it, and most won’t flag it. I think there’s a potentially deeper and more nuanced meaning, but that is a subject for another essay.

Yellow is for watersports. Thirsty? Want a sip from the source? Flag right. Need to drain? No need for indoor plumbing when there’s a line of waterboys by the men’s room. On them or in them: flag left. Liquid sunshine, good to the last drop, piss scenes are raunchy. Piss is considered a subset of raunch, which is an attraction to and emphasis on body fluids, excretions and the like. Prolific author and leather lifestyle columnist Larry Townsend commented on the appeal of this taste:

The sensation of warm piss across the skin is much the same as water from a shower head, but the knowledge of its source puts it in a category all its own. For the giver there is a real sense of power and domination. It is common enough to say ‘piss on you’ to someone, but actually to do it…6

Green began with what is sometimes called the world’s oldest profession. Green, the colour of money, was associated with the tricks of the trade: hustlers and their clients. The original code had only one green and it was coded to sex work. In 1972, the Daddy/boy scene had not really emerged. When it did, green became more associated with that and less with pay-to-play. They are, however, adjacent, and in the more detailed iterations of the code, kelly green is associated with hustlers and johns and hunter green with Daddies and boys. Sugar for sugar; sweets for the sweet: the Sugar Daddy, a sex worker’s favourite client, one they might genuinely like and who pays the bills consistently, morphs into the Daddy of the contemporary Daddy/boy scene, a mythic figure who did not exist as such at the advent of the hanky code system. With this transformation, the colour green moves from the marketplace to the family room.

Blue, navy and light, map onto the most iconic of gay male sexual activities, both of which are shared by mainstream vanilla as well as alternative pervert guys. They are probably also the practises most likely to be shared with heterosexuals and other groups identifiable by specific sexual tastes, proclivities or identities. They are of course, fucking and sucking respectively. Fuckers flag navy blue left. Cocksuckers flag light blue right.

Black signifies heavy S/M, sadomasochism. This is the hard stuff. Black means pain. Dig dishing it? Flag left. Can you take it? Fly right. While certain colours are associated with fairly narrow tastes and practises, others are broader and black is deep and wide. How many ways are there to hurt and be hurt? They all fit under the big black umbrella. Often the codes cross: certainly pain is associated with purple, for instance. Piercings hurt. The pain involved may or may not be central. In black, it is centred.

Roped up, tied down, cuffed, caged, chained, restrained, put in a sack: can’t move at all. Grey is for bondage. It’s the colour of handcuffs, of many metals, but it can signify rope bondage or other methods of restraint as well. Bondage is often a first kink, sometimes an only kink and like its counterpoint and code colour grey, mixes well with others, often enhancing and highlighting other practises.

Brown is wholly shit. Like its raunchy counterpoint, yellow, its coded colour is a visual analog for the substance its adherents enjoy. Scat fans are a minority within a minority and face a certain amount of social critique, even within kinky circles, for their unusual tastes. While fudge-packing jokes may be a staple of gay-baiting comedy routines, the reality is that most gay men who practice anal sex know how to clean out. If it’s dirty, it is probably meant to be. It is somewhat surprising that brown was included in the original code since it maps onto an uncommon practice. Certainly more common and popular tastes were not included in the original code. However, given the origin of the code in an overstocking episode, its presence may be attributable to the practical reality of what colours were actually available. The simplicity of assigning brown to the rare shit fetish may have come about because yellow was the obvious choice for the more common and popular taste for piss.

But wait: there’s more. From a few basic colours of bandanas, there evolved over time an arcane array of specialty colours (and coded objects) conveying what are in many cases equally obscure sexual practises. Including four intended as jokes, and omitting one he considered too dangerous to include, Trevor Jacques listed seventy-one coded colours and objects in his 1993 manual On the Safe Edge.7) Some of these arose to meet a need. Shaving, spitting, food fetish and foot fetish are certainly charged enough practises and invisible enough for fans to find inclusion in the code useful. Burgundy, pale yellow, lime green and coral oblige. Others could be apocryphal, perhaps appearing nowhere but on the printed reproductions of the code itself. A few seem redundant. While a ‘chubby chaser’ might flag apricot right, why would ‘two tons o’ fun’ need any indication beyond his own corporeality? Some may be jokes. Certainly the acknowledged joke of a stalk of celery suggesting the flagger was either offering brunch or out to brunch is simply out to lunch. But a teddy bear to indicate cuddling seems cute if silly, and a kewpie doll worn left to indicate the flagger’s ‘chicken’ or underage status is just weird. Coded objects can be self-referential and practical, as much about having the gear at hand as signalling a preference. Incorporating a skein of rope itself into one’s sartorial gear not only signals an interest in rope bondage, it also keeps the tool of the kink available for use at any time. The same would be true of wearing floggers, whips, paddles and other impact implements, although these are not typically included in the code. A wire brush, indicating abrasion play, is included in Jacques’ list. Probably uncommon in practice, its inclusion does tend to emphasise the potentially infinite flexibility of object coding.

There are of course, bugs in the code. There are variations in the origin stories and disagreements about specific meanings. The obscure tastes that are coded contrast with the more common ones that are absent and beg the question why. Where is bootlicking? Breath control? Verbal? Even dominance and submission is missing. It does not automatically map on to other practises as much as it might seem to do so. This is not a call for inclusion, just an acknowledgement of omission. The next generation is also always bringing fresh ideas and practises.

Decay and growth in a system of communication mean meanings change over time. In the twenty-first century it is more apparent than ever that safety is an illusion. Sanity remains a construct of nineteenth-century psychoanalysis. And consent is arguably a gray area. Idealism based on notions of purity is dangerous. Now more than ever we need the skills to deploy and read subtle code. This is not just about bandanas. What are you saying with what you are wearing? Sometimes a hanky is just a hanky. Sometimes a cigar is just a cigar. But usually, there is a lot more to it than that.

Dr. Jordy Jones is an independent scholar, curator and artist. He is the author of The Mayor of Folsom Street and an honorary member of the 15 Association.

Photograph courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art (www.moma.org).

M Jakobsen, ‘The History of the Bandana.’ Retrieved February 2018 from: https://www.heddels.com/2017/05/the-history-of-the-bandana/ ↩

R Davolt, Painfully Obvious: An Irreverent & Unauthorized Manual for Leather/SM. Los Angeles, Daedalus Publishing, 2003, 229 ↩

J Jones. The Mayor of Folsom Street: The Auto/biography of ‘Daddy’ Alan Selby, aka Mr. S. Springfield, Fair Page Media, 2017, 61-62 ↩

Ibid. 62. ↩

J Ward. Running the Gauntlet: An Intimate History of the Modern Piercing Movement. Gauntlet Enterprises, 2011, 46-47 ↩

L Townsend, The Leatherman’s Handbook II. New York, Carlyle Communications, 1983, 152 ↩

T Jacques, On the Safe Edge: A Manual for SM Play. Toronto, WholeSM Publishing, 1993, Appendix E 2-3 ↩