IN MAY 1997, POLITICS intervened with fashion when U.S. President Bill Clinton addressed the White House at a press conference with concern over designers glorifying the so-called ‘heroin chic’. He explained that, ‘In the press in recent days, we’ve seen reports that many of our fashion leaders are now admitting – and I honour them for this – they’re admitting flat-out that images projected in fashion over the last few years have made heroin addiction seem glamorous and sexy and cool.’ He went on, ‘the glorification of heroin is not creative, it’s destructive. It’s not beautiful, it is ugly. And it’s not about art; it’s about life and death.’1

The political statement marked a seminal moment for the ‘heroin chic’ aesthetic that became mainstream in fashion during the Nineties through advertising campaigns and editorials. But the look had broader implications, evolving from its original incarnation as documentary-style fashion photography into the minimalist grunge style adopted by designers in the latter years of the decade, such as Jil Sander, Helmut Lang and Josephus Thimister.

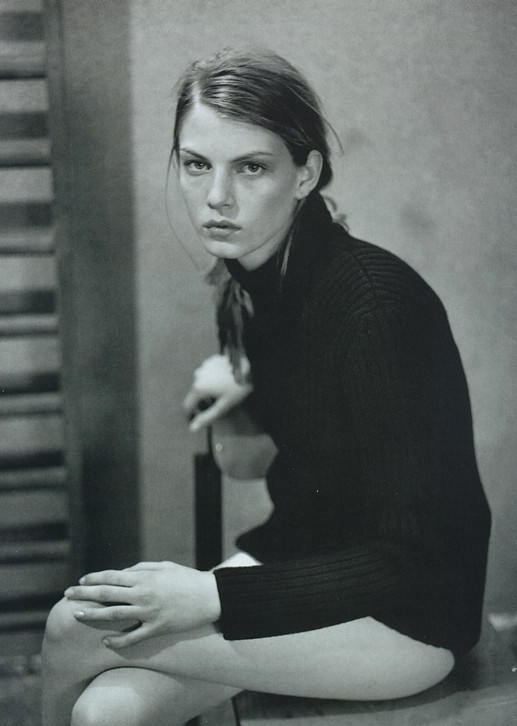

Emerging from fashion photography and styling that was intended as more realistic portrayal of fashion, the androgynous waif was a subversive take on mainstream fashion. Models appeared rakishly skinny, doe-eyed and pale skinned, framed in awkward and off-centre positions that suggested they were either sleep-deprived or using drugs, which they often were. Haphazard styling that made the model look like she or he was either still in last night’s clothes, or had hurriedly dressed themselves. Underlying this ‘de-glamourisation’ of the fashion image was a celebration of hedonism and youth through the grunge of drug culture. This imagery presented a more honest take on the fashion image, with publications like The Face and i-D and their creative teams trailblazing the aesthetic. Kate Moss became the face of the generation, from her early images with Corinne Day to her subsequent Calvin Klein campaigns.

The stark images from this era were a reaction to the opulent glamour of fashion during the Eighties. As Amy M. Spindler phrases it in her 1998 article for The New York Times, ‘heroin chic’ reacted to ‘the maniacally jolly group shots of the campaigns of Tommy Hilfiger and Ralph Lauren.2

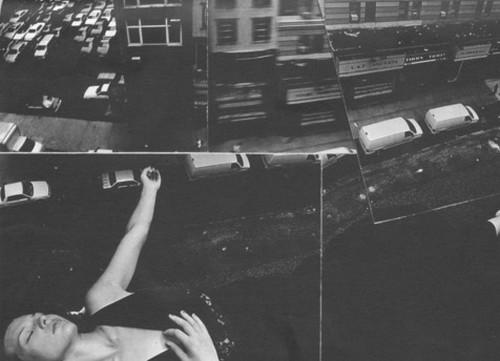

It was a rejection of the bronzed and buffed culture of the former generation coupled with the rising hedonism of Generation X. Photographers like Corinne Day, Davide Sorrenti and Juergen Teller sought to give a revealing and honest look at fashion as it really was, capturing moments that revealed the reality behind a polished fashion image. The intention was to subvert the fashion image by glorifying the seediness behind.

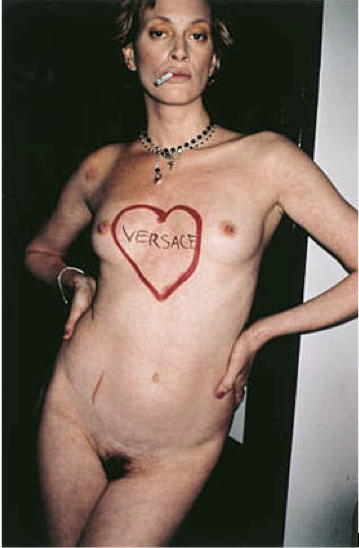

In a recent interview with SHOWstudio’s Nick Knight, model Kristen McMenamy sheds light on the famous image of her, naked with ‘Versace’ emblazoned in lipstick across her chest taken by Juergen Teller. It is an image that has, in many respects, defined the era as a starkly honest portrayal of fashion. The model explains that, ‘it was the first time that photographers were actually allowed to capture [models], as documentary.’3 The gesture marks a clear departure from the high glamour and elaborate, big-budget fashion campaigns of the Eighties, orchestrated by brands like Versace. Still in the tradition of fashion, the look of ‘heroin chic’ embraced an honest, bare-all approach that literally stripped back the layers of the fashion image.

The ‘heroin chic’ aesthetic set the parameters for the generation of the waif that became popular in the mainstream. The image of the emaciated, child-like physique still suggested the effects of drug-taking culture in its later, more watered-down incarnations. Journalist Robin Givhan pointed the blame at the fashion industry for promoting these behaviours. She wrote in an article for The Washington Post in 1996 that, ‘Editors and photographers have been fond of posing [models] in dingy bathrooms or cheap motels with their makeup smeared and their hair tousled. And while they may be wearing the latest pricey designer clothes, the implication is that a hypodermic is somewhere just outside of the frame.’4 Indeed, outside the frame drug culture was hitting the mainstream, with films like ‘Trainspotting’ and ‘Kids’ which presented the archetype of the reckless youth, a reality behind many of these fashion images.

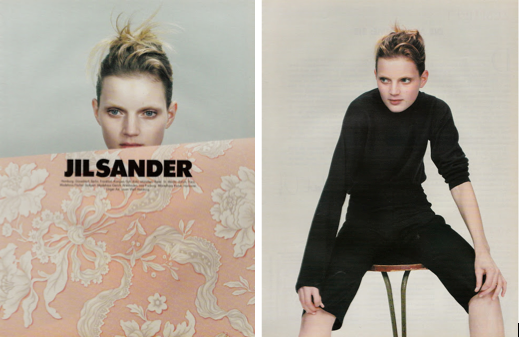

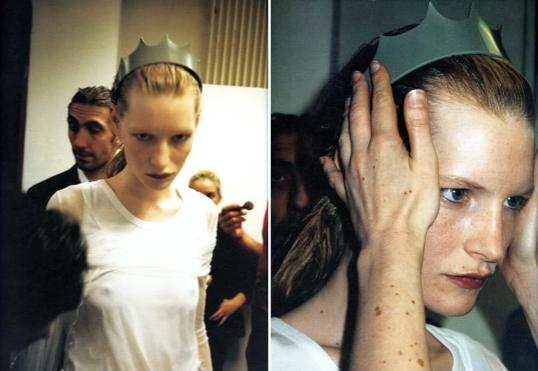

For all its controversy ‘heroin chic’ became a popular term in fashion media, readily applied to any image that presented a sort of minimalist, grunge look. Designers like Helmut Lang, Prada and Jil Sander and their stylists and photographers embraced this aesthetic to varying degrees, merging art and fashion in a way that evolved from the earlier, grungier, fashion images. This second wave of the waif presented a more artful aesthetic that still rejected the opulence and glamour of the traditional fashion image, by using minimal make-up and pale skin in styling that appeared to be unchoreographed.

As if to highlight the link between the two generations of the waif, Jil Sander was criticised for promoting ‘heroin chic’ in her spring/summer 1996 campaign by Craig McDean. One image featured the model Guinevere Van Seenus posing with her sleeve rolled up above the elbow in what apparently suggested heroin use. Sander rejected the claim that the image was a reference to ‘heroin chic,’ defending the campaign by explaining that, ‘This makeup has nothing to do with the drug scene.’ Instead she argued that, ‘It has something to do with sensitivity and refinement, and going away from the old fashion world. We are not in the old time. Sometimes you have to punch harder to go forward. We can’t go back to the old idea of beauty.’5

What Jil Sander meant by ‘sensitivity and refinement’ refers to the language of modern simplicity that the designer has made a name for herself with, alongside her Nineties minimalist counterparts Helmut Lang, Josephus Thimister, Ann Demeulemeester and others. These designers brought the pale, waif-like cover girl into the latter years of the decade. This newer look that was defined by its own set of ideals but it remained in step with the rawness of the documentary-style fashion of the former years (as seen with Juergen Teller and Corinne Day).

Although the strength of the argument against Sander’s image campaign might seem stretched, to a large extent ‘heroin chic’ appears to be embedded in the DNA of her images and others like them. Trends, after all, evolve from the collective of a former generation, and constantly react to and build on existing cultural ideals. Today we, somewhat nostalgically, remember ‘heroin chic’ as an integral Nineties fashion phenomenon, and as such it is an essential part of the aesthetic language of the era. Considering the controversy surrounding ‘heroin chic’ at the time, big brands were understandably reluctant to overtly subscribe to the aesthetic. Nevertheless, it’s of course absolutely vital to fashion brands not to lag behind the trends; a fashion brand needs to remain in fashion. And so, in a complex manoeuvre intended to allow high fashion companies to keep old customers while enticing new ones, it’s hardly surprising that overtly distancing themselves from ‘heroin chic’ while covertly observing the trend must have seemed like the only way forward. Appearing to challenge the status quo while remain suitably politically correct is then perhaps just another way of both having your cake and eating it.

Laura Gardner is Vestoj’s former Online Editor and a writer in Melbourne.

‘The Death Proclamation of Generation X’ by Maxim W. Furek, 2008. ↩

‘Critic’s Notebook; Tracing the Look of Alienation’ by Amy M. Spindler for The New York Times, March 24, 1998. ↩

‘Subjective’ which featured Kristen McMenamy interviewed by Nick Knight for SHOWStudio, 2014. ↩

‘Why Dole Frowns on Fashion’ by Robin Givhan for The Washington Post, 1996. ↩

‘The 90’s Version of the Decadent Look’ by Amy M. Spindler for The New York Times, May 7, 1996. ↩