TODAY, AUSTRIAN-AMERICAN DESIGNER Rudi Gernreich (1922-85) is best known for his topless bathing suit, or the ‘monokini’ as it was dubbed, embodied by Peggy Moffitt. This iconic image, alongside his so-called ‘kooky’ designs in psychedelic colours and sleek, space-age silhouettes have come to popularly define his body of work. As a designer, he defined an era; fashion journalist for The New York Times, Bernardine Morris called him ‘the country’s leading avant-garde designer of the 1950s and 60’s. However Gernreich’s influence was more profound: from his involvement in the early strands of America’s gay rights movement, to his bold and often controversial statements he made as a designer that questioned the role of fashion in culture. Despite this, Gernreich has become more of a footnote in fashion history than a cultural icon of a generation, a title more deserving of the dynamic designer.

The designer’s story begins in the grim setting of pre-War Europe. Gernreich and his Jewish mother fled Vienna for California soon after the Nazis accessioned Austria in 1937. After a few short stints in Hollywood, such as his job sketching for famed costume designer Edith Head (much later he crafted delightful costumes for Otto Preminger’s awesomely bad musical Skidoo), he started producing designs for the fashion industry in 1950. Around this time, he became romantically involved with Harry Hay, a political activist often called the founder of the modern gay rights movement. During their three-year relationship, they co-founded the Mattachine Society, America’s first gay rights organisation. Gernreich’s participation in the group was brief but crucial; it lasted only a few years, and afterwards he never publicly acknowledged his homosexuality again. His co-founder and ex-partner Hay went in the other direction, going on to found the Radical Faeries, a ‘gay hippie’ group, in the 1970s, a group that continues to have active memberships internationally today.

Gernreich’s brief, but influential involvement in the history of the gay rights movement survives in a Mattachine notebook in the designer’s archive at UCLA in California. One particular page shows notes for a planned discussion about ‘camping’ – acting outrageous and effeminate. The tone of his questions is surprisingly circumspect for 1951, and reads: ‘Since we agree that camping is conscious homo [sic] expression, what then is unconscious homosexual behavior [?]’ and, ‘How can camping become an acceptable homosexual expression?’ After leaving the group (and Hay) in 1953, Gernreich never publicly acknowledged this or any association with gay rights again, although his work as a designer continued to embody ideas of radical thought and personal expression. When Gernreich’s topless bathing suit first appeared in 1964, the design was a succès de scandale, inspiring some 20,000 press articles in response. The design was created on the suggestion of Susanne Kirtland, editor at Look magazine, reading Gernreich’s pronouncements about the impending craze for ‘toplessness’. Kirtland contacted the designer in 1962 and asked him to make a topless suit, he demurred, fearing it would ruin his career. Kirtland’s response was, ‘Oh, but you’ve got to; I’ve already had clearance from the front office.’ Gernreich finally conceded, motivated by the fear that his competitor, Emilio Pucci, would make a topless suit first. Though the design was not a commercial success (only 3,000 copies of the suit sold), this single garment put Gernreich in the history books for its risqué and revealing nature. But this was not the statement the designer intended. For Gernreich, the gesture had roots in his European upbringing; the garment was progressive, and implicitly feminist: if men can go topless, why can’t women? In an essay for a touring retrospective of the designer’s work, ‘Fashion Will Go Out of Fashion’, author Elfriede Jelinek underscores the suit’s value, explaining that Gernreich ‘doesn’t do it to emphasise the nakedness of the top half of the woman’s body. Instead, in partially exposing this part of the body, he clothes it, but in a different way, and thus re-creates it.’ Despite this, the American media’s response was leering and thereafter Gernreich became associated with the ‘kookiness’ and ‘crazy’ styles of this revolutionary period of the mid-sixties, a cliché he never managed to escape.

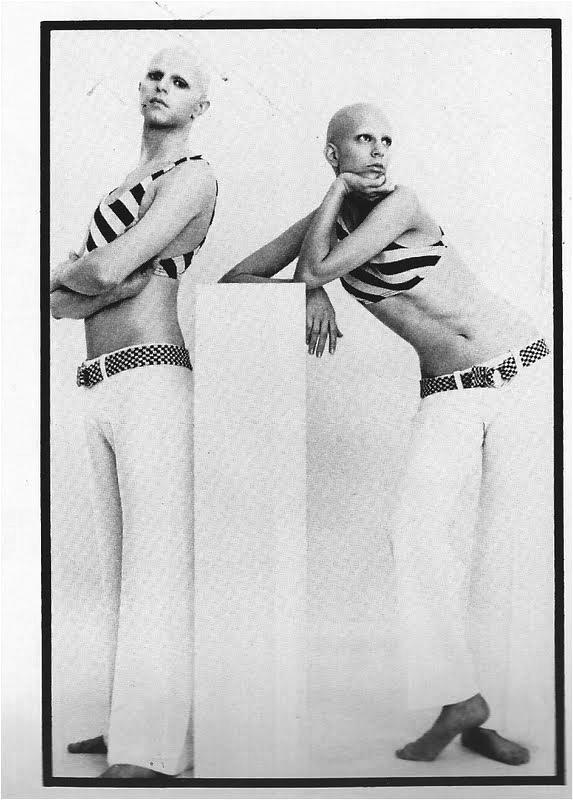

In 1967, at the height of his fame, Gernreich shuttered his atelier, telling The New York Times that he was ‘exhausted’. He never mounted a major collection again but continued to offer dire predictions to the press. In 1970, Life magazine asked him to predict the future of fashion, Gernreich arranged for a pair of models to appear nude, and completely shaved, at a promotional event. He later explained, ‘What unisex means is that we are beyond pathology, and fashion is finished.’ The death of fashion became his great theme: ‘Fashion will go out of fashion,’ he told Forbes. To another interviewer, he said, ‘I’m not out to kill fashion. It’s already finished. The word has no meaning. It stands for all the wrong values. Snobbism, wealth, the select few. It’s antisocial. It isolates itself from the masses. Today you can’t be antisocial, so fashion is gone. Even the word has become a little embarrassing. Clothes. Gear. These are the words of today.’ These broadsides did little to aid the designer’s career, and were largely ignored by the fashion press.

Two years after his death in 1985, Peggy Moffitt, his muse and friend, gave an interview to the Fashion Institute of Technology that reveals the limitations of his activist approach for the designer. She explains that, ‘He liked the idea of being the prophet. It’s great to prophesise, but then you say, “Peggy, can we see the first piece?”… He loved being in the headlines. But he didn’t love making these clothes any more.” When examined more closely, Gernreich’s career has a profound implications beyond his ‘monokini’ design. He was an activist at heart, with progressive and controversial design statements that were often misunderstood by the press. What the industry wanted was the ‘kooky’ clothes so popular at the time; but what Gernreich had was an abundance of ideas. It’s interesting to speculate, fifty years after this radical – and misinterpreted – gesture of toplessness, whether he spent his final years wishing he had never made that bathing suit at all.

Alexander Joseph is a freelance writer and editor in fashion.