THAT WINTER WAS A long time going. A freezing wind blew through the streets of the city, and overhead the snow clouds moved across the sky.

The old man who was called Drioli shuffled painfully along the sidewalk of the Rue de Rivoli. He was cold and miserable. He moved glancing without any interest at the things in the shop windows – perfume, silk ties and shirts, diamonds, furniture, books. Then a picture gallery. He had always liked picture-galleries. This one had a single canvas on display in the window. He stopped to look at it. Suddenly, there came to him a slight movement of the memory, a distant recollection of something, somewhere, he had seen before. He looked again. It was landscape, a group of trees leaning over to one side as if blown by wind. Attached to the frame there was a little plaque, and on this it said: CHAIM SOUTINE (1894 – 1943). Drioli stared at the picture, wondering vaguely what there was about it that seemed familiar. Crazy painting, he thought. Very strange and crazy – but I like it… Chaim Soutine… Soutine… ‘By God!’ he cried suddenly. ‘My little friend, with a picture in the finest shop in Paris! Just imagine that!’

The old man pressed his face closer to the window. He could remember the boy – yes, quite clearly he could remember him. But when? The rest of it was not so easy to recollect. It was so long ago. How long? Twenty – no, more like thirty years, wasn’t it? Wait a minute. Yes – it was the year before the war, the first war, 1913. That was it. And this Soutine, this ugly little boy whom he had liked – almost loved – for no reason at all that he could think of, except that he could paint.

And how he could paint! It was coming back more clearly now. Where was it the boy had lived?

The Cité Falguière that was it. Then there was the studio with the single chair in it, and the dirty red sofa that the boy had used for sleeping; the drunken parties, the cheap white wine, the furious quarrels, and always, always the sad face of the boy thinking over his work. It was odd, Drioli thought, how easily it all came back to him now, how each single small remembered fact seemed instantly to remind him of another.

There was that nonsense with the tattoo, for instance. Now, that was a mad thing if ever there was one. How had it started? Ah, yes – he had got rich one day, that was it, and he had bought lots of wine. He could see himself now as he entered the studio with the parcel of bottles under his arm – the boy sitting before the easel, and his (Drioli’s) own wife standing in the centre of the room, posing for her picture.

‘Tonight we shall celebrate,’ he said. ‘We shall have a little celebration, us three.’

‘What is it that we celebrate?’ the boy asked, without looking up. ‘Is it that you have decided to divorce your wife so she can marry me?’

‘No,’ Drioli said. ‘We celebrate because today I have made a great sum of money with my work.’

‘And I have made nothing. We can celebrate that also.’

The girl came across the room to look at the painting. Drioli came over also, holding a bottle in one hand, a glass in the other.

‘No!’ the boy shouted. ‘Please – no!’ He snatched the canvas from the easel and stood it against the wall. But Drioli had seen it.

‘It’s marvellous. I like all the others that you do, it’s marvellous. I love them all.’

‘The trouble is,’ the boy said, gloomily, ‘that in themselves they are not nourishing. I cannot eat them.’

‘But still they are marvellous.’ Drioli handed him a glass of the pale-yellow wine. ‘Drink it,’ he said. ‘It will make you happy.’ Never, he thought, had he known a more unhappy person, or one with a gloomier face.

‘Give me some more,’ the boy said. ‘If we are to celebrate then let us do it properly.’

‘Tonight we shall drink as much as we possibly can,’ Drioli said. ‘I am exceptionally rich. I think perhaps I should go out now and buy some more bottles. How many shall I get?’

‘Six more,’ the boy said. ‘Two for each.’

‘Good. I shall go now and fetch them.’ ‘And I will help you.’

In the nearest cafe Drioli bought six bottles of white wine, and they carried them back to the studio. Then they sat down again and continued to drink.

‘It is only the very wealthy, who can afford to celebrate in this manner.’

‘That is true,’ the boy said. ‘Isn’t that true, Josie?’ ‘Of course.’ ‘Beautiful wine,’ Drioli said. ‘It is a privilege to drink it.’ Slowly, methodically, they set about getting themselves drunk. The process was routine, but all the same there was a certain ceremony to be observed.

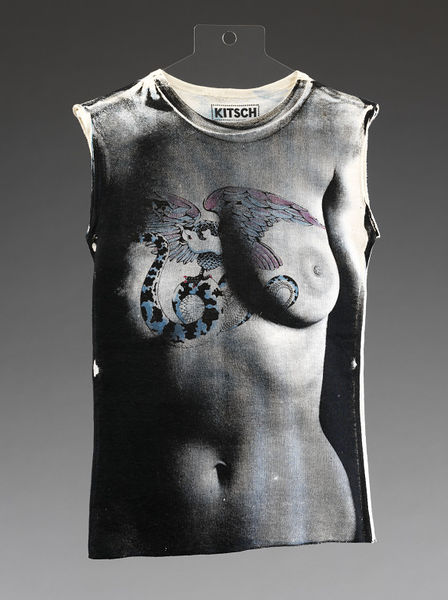

‘Listen,’ Drioli said at length. ‘I have a tremendous idea. I would like to have a picture, a lovely picture. – … It is this. I want you to paint a picture on my skin, on my back. Then I want you to tattoo over what you have painted so that it will be there always.’

‘You have crazy ideas,’ the boy said.

‘I will teach you how to use the tattoo. It is easy. A child could do it.’

‘You are quite mad. What is it you want?’

‘I will teach you in two minutes.’

‘Impossible!’

‘Are you saying I do not know what I am talking about?’

‘All I am saying,’ the boy told him, ‘is that you are drunk and this is a drunken idea.’

‘We could have my wife for a model. A study of Josie upon my back.’

‘It is no good idea,’ the boy said. ‘And I could not possibly manage the tattoo.’

‘It is simple. I will undertake to teach you in two minutes. You will see. I shall go now and bring the instruments.’

In half an hour Drioli was back. ‘I have brought everything,’ he cried, waving a brown suitcase. ‘All the necessities of the tattooist are here in this bag.’

He placed the bag on the table, opened it and laid out the electric needles and the small bottles of coloured inks. He plugged in the electric needle, then he took the instrument in his hand and pressed a switch. He threw off his jacket and rolled up his left sleeve. ‘Now look. Watch me and I will show you how easy it is. I will make a design on my arm, here. … See how easy it is … see how I draw a picture of a dog here upon my arm …’ The boy was intrigued. ‘Now let me practise a little – on your arm.’ With the buzzing needle he began to draw blue lines upon Drioli’s arm. ‘It is simple,’ he said. ‘It is like drawing with pen and ink. There is no difference except that it is slower.’

‘There is nothing to it. Are you ready? Shall we begin?’ ‘At once.’ ‘The model!’ cried Drioli. ‘Come on, Josie!’ He was in a bustle of enthusiasm – now arranging everything, like a child preparing for some exciting game. ‘Where will you have her? Where shall she stand?’

‘Let her be standing there, by my dressing table. Let her be brushing her hair. I will paint her with her hair down over her shoulders and her brushing it.’ ‘Tremendous. You are a genius.’

‘First,’ the boy said, ‘I shall make an ordinary painting. Then if it pleases me, I shall tattoo over it.’ With a wide brush he began to paint upon the naked skin of the man’s back.

‘Be still now! Be still’ His concentration, as soon as he began to paint, was so great that it appeared somehow to neutralize his drunkenness. ‘All right. That’s all,’ he said at last to the girl.

Far into the small hours of the morning the boy worked. Drioli could remember that when the artist finally stepped back and said, ‘It is finished,’ there was daylight outside and the sound of people walking in the street.

‘I want to see it,’ Drioli said. The boy held up a mirror, and Drioli craned his neck to look.

‘Good God!’ he cried. It was a startling sight. The whole of his back was a blaze of colour – gold and green and blue and black and red. The tattoo was applied so heavily it looked almost like an impasto. The portrait was quite alive; it contained so much characteristic of Soutine’s other works. ‘It’s tremendous!’

‘I rather like it myself.’ The boy stood back, examining it critically. ‘You know,’ he added, ‘I think it’s good enough for me to sign.’ And taking up the machine again, he inscribed his name in red ink on the right-hand side, over the place where Drioli’s kidney was.

***

The old man who was called Drioli was standing in a sort of trance, staring at the painting in the window of the picture-dealer’s shop. It had been so long ago, all that – almost as though it had happened in another life.

And the boy? What had become of him? He could remember now that after returning from the war – the first war – he had missed him and had questioned Josie. ‘Where is my little painter?’

‘He is gone,’ she had answered. ‘I do not know where.’

‘Perhaps he will return.’

‘Perhaps he will. Who knows?’

That was the last time they had mentioned him. Shortly afterwards they had moved to Le Havre where there were more sailors and business was better. Those were the pleasant years, the years between the wars, with the small shop near the docks and the comfortable rooms and always enough work. Then had come the second war, and Josie being killed, and the Germans arriving, and that was the finish of his business. No one had wanted pictures on their arms any more after that. And by that time he was too old for any other kind of work. In desperation he had made his way back to Paris, hoping vaguely that things would be easier in the big city. But they were not.

And now, after the war was over, he possessed neither the means nor the energy to start up his small business again. It wasn’t very easy for an old man to know what to do, especially when one did not like to beg. Yet how else could he keep alive?

Well, he thought, still staring at the picture. So that is my little friend. He put his face closer to the window and looked into the gallery. On the walls he could see many other pictures and all seemed to be the work of the same artist. There were a great number of people strolling around. Obviously it was a special exhibition. On a sudden impulse, Drioli turned, pushed open the door of the gallery and went in. It was a long room with a thick wine-coloured carpet, and by God how beautiful and warm it was! There were all these people strolling about looking at the pictures, well-washed dignified people, each of whom held a catalogue in the hand. He heard a voice beside him saying, ‘What is it you want?’

Drioli stood still. ‘If you please,’ the man in a black suit was saying, ‘take yourself out of my gallery.’

‘Am I not permitted to look at the pictures?’

‘I have asked you to leave.’ Drioli stood his ground. He felt suddenly, overwhelmingly outraged. ‘Let us not have trouble,’ the man was saying. ‘Come on now, this way.’ He put a fat white hand on Drioli’s arm and began to push him firmly to the door. That did it.

‘Take your goddam hands off me!’ Drioli shouted. His voice rang clear down the long gallery and all the heads turned around as one – all the startled faces stared down the length of the room at the person who had made this noise. The people stood still, watching the struggle. Their faces expressed only an interest, and seemed to be saying. It’s all right. There’s no danger to us. It’s being taken care of.

‘I, too!’ Drioli was shouting. ‘I, too, have a picture by this painter! He was my friend and I have a picture which he gave me!’

‘He’s mad.’ ‘Someone should call the police.’

With a twist of the body Drioli suddenly shook off the man and before anyone could stop him he was running down the gallery shouting, ‘I’ll show you! I’ll show you! I’ll show you!’ He flung off his overcoat, then his jacket and shirt, and he turned so that his naked back was towards the people.

‘There!’ he cried, breathing quickly. ‘You see? There it is!’

There was a sudden absolute silence in the room, each person arrested in what he was doing, standing motionless in a kind of shocked, uneasy surprise. They were staring at the tattooed picture. It was still there, the colours as bright as ever. Somebody said, ‘My God, but it is!’ ‘His early manner, yes?’ ‘It is fantastic, fantastic!’ ‘And look, it is signed!’ ‘Old one, when was this done?’

‘In 1913,’ Drioli said, without turning around. ‘In the autumn of 1913.’ ‘Who taught Soutine to tattoo?’ ‘I taught him.’ ‘And the woman?’

‘She was my wife.’

The gallery owner was pushing through the crowd towards Drioli. He was calm now, deadly serious, making a smile with his mouth. ‘Monsieur,’ he said, ‘I will buy it. I said I will buy it. Monsieur.’ ‘How can you buy it?’ Drioli asked softly. ‘I will give two hundred thousand francs for it.’ ‘Don’t do it!’ someone murmured in the crowd. ‘It is worth twenty times as much.’

Drioli opened his mouth to speak. No words came, so he shut it; then he opened it again and said slowly, ‘But how can I sell it?’ He lifted his hands, let them drop helplessly to his sides. ‘Monsieur, how can I possibly sell it?’ All the sadness in the world was in his voice. ‘Yes!’ they were saying in the crowd. ‘How can he sell it? It is part of himself!’

‘Listen!’ the dealer said, coming up close. ‘I will help you. I will make you rich. Together we shall make some private arrangement over this picture, no?’

Drioli watched him with worried eyes. ‘But how can you buy it. Monsieur? What will you do with it when you have bought it? Where will you keep it? Where will you keep it tonight? And where tomorrow?’

‘Ah, where will I keep it? Yes, where will I keep it? Well, now … It would seem,’ he said, ‘that if I take the picture, I take you also. That is a disadvantage. The picture itself is of no value until you are dead. How old are you, my friend?’ ‘Sixty-one.’

‘But you are perhaps not very healthy, no?’ The dealer looked Drioli up and down, slowly, like a farmer examining an old horse.

‘I do not like this,’ Drioli said moving away. ‘Quite honestly. Monsieur, I do not like it.’ He moved straight into the arms of a tall man who put out his hands and caught him gently by the shoulders.

‘Listen, my friend,’ the stranger said, still smiling. ‘Do you like to swim and to lie in the sun?’

Drioli looked up at him, rather startled. ‘Do you like fine food and red wine from the great chateaux of Bordeaux?’ The man was still smiling, showing strong white teeth with a flash of gold among them. He spoke in a soft manner, one gloved hand still resting on Drioli’s shoulder. ‘Do you like such things?’

‘Well – yes,’ Drioli answered, still greatly puzzled. ‘Of course.’

‘Have you ever had a shoe made especially for your own foot?’ ‘No.’ ‘You would like that?’

‘Well…’

‘And a man who will shave you in the mornings and trim your hair?’ Drioli simply stood and stared.’And a plump attractive girl to manicure the nails of your fingers?’ Someone in the crowd giggled. ‘And a bell beside your bed to call a maid to bring you breakfast in the morning? Would you like these things, my friend? Do they appeal to you?’ Drioli stood still and looked at him.

‘You see, I am the owner of the Hotel Bristol in Cannes. I now invite you to come down there and live as my guest for the rest of your life in luxury and comfort.’ The man paused, allowing his listener time to digest this cheerful prospect. ‘Your only duty – shall I call it your pleasure – will be to spend your time on my beach in bathing trunks, walking among my guests, sunning yourself, swimming, drinking cocktails. You would like that?’ There was no answer.

‘Don’t you see – all the guests will thus be able to observe this fascinating picture by Soutine. You will become famous, and men will say, ‘Look, there is the fellow with ten million francs upon his back.’ You like this idea, Monsieur? It pleases you?’

Drioli looked up at the tall man in the canary gloves. He said slowly, ‘But do you really mean it?’

‘Of course I mean it.’

‘Wait,’ the dealer interrupted. ‘See here, old one. Here is the answer to our problem. I will buy the picture, and I will arrange with a surgeon to remove the skin from your back, and then you will be able to go off on your own and enjoy the great sum of money I shall give you for it.’

‘With no skin on my back?’

‘No, no, please! – You misunderstand. This surgeon will put a new piece of skin in the place of the old one. It is simple.’

‘Could he do that?’

‘There is nothing to it.’

‘Impossible!’ said the man with the canary gloves. ‘He’s too old for such a major skin-removing operation. It would kill him. It would kill you, my friend.’

‘It would kill me?’

‘Naturally. You would never survive. Only the picture would come through.’

‘In the name of God!’ Drioli cried. He looked around terrified at the faces of the people watching him, and in the silence that followed, another man’s voice, speaking quietly from the back of the group, could be heard saying, ‘Perhaps, if one were to offer this old man enough money’, he might consent to kill himself on the spot. Who knows?’ A few people laughed. The dealer moved his feet uneasily on the carpet.

‘Come on,’ the tall man said, smiling his broad white smile. ‘You and I will go and have a good dinner and we can talk about it some more while we eat. How’s that? Are you hungry?’

Drioli watched him, frowning. He didn’t like the man’s long flexible neck, or the way he craned it forward at you when he spoke, like a snake.

‘Roast duck and Chambertin,’ the man was saying. ‘And perhaps a soufflé aux marrons, light and frothy.’ Drioli’s eyes turned up towards the ceiling, his mouth watered.

‘How do you like your duck?’ the man went on. ‘Do you like it very brown and crisp outside, or shall it be…’

‘I am coming,’ Drioli said quickly. Already he had picked up his shirt and was pulling it hurriedly over his head. ‘Wait for me. Monsieur. I am coming.’ And within a minute he had disappeared out of the gallery with his new patron.

It wasn’t more than a few weeks later that a picture by Soutine, of a woman’s head, painted in an unusual manner, nicely framed and heavily varnished, turned up for sale in Buenos Aires. That – and the fact that there is no hotel in Cannes called Bristol – causes one to wonder a little, and to pray for the old man’s health, and to hope strongly that wherever he may be at this moment, there is a plump attractive girl to manicure the nails of his fingers, and a maid to bring him his breakfast in bed in the mornings.

Roald Dahl was a British novelist, poet, and short story writer. ‘Skin’ was originally published in 1952 in The New Yorker.