The part around the neck of a shirt, blouse, jacket or coat, either upright or turned over. (Noun)

Seize or apprehend (someone). (Verb)

Oxford English Dictionary

MUCH OF OUR UNDERSTANDING, and indeed experience, of dress comes from the language we use to describe it. The etymology of dress reveals the historical changes in our understanding and use of clothes. The phonetic titling of a word is also inherent in our experience of it; take the word ‘suede’ which rolls off the tongue with a similar texture to the velvety fabric itself, an obvious example of how interactive this relationship can be. More often than not there is a profound dynamic between a word and its function as an object.

The word ‘collar’ presents a sort of curt simplicity that seems to fit its form and function as an object of dress. Thought to originate around 1300, the term originates from the old French ‘coler’, referring to the neck, which formed from the Latin term ‘collum’ having a similar meaning. There is something delightful and logical about the concept of the shirt collar deriving from the image of an architectural column.

Like many other sartorial terms, ‘collar’ presents an interesting interplay between noun and verb, with the action of ‘collaring’ someone being to grab them by the neck. Later into the twentieth-century with the rise of corporate industries and the development of the archetypal modern suit as we know it today, the collar came to have powerful social connotations within the context of menswear. The term ‘white-collar’ represents a hierarchical distinction from its counterpart ‘blue-collar’ (or perhaps even ‘pink-collar’).

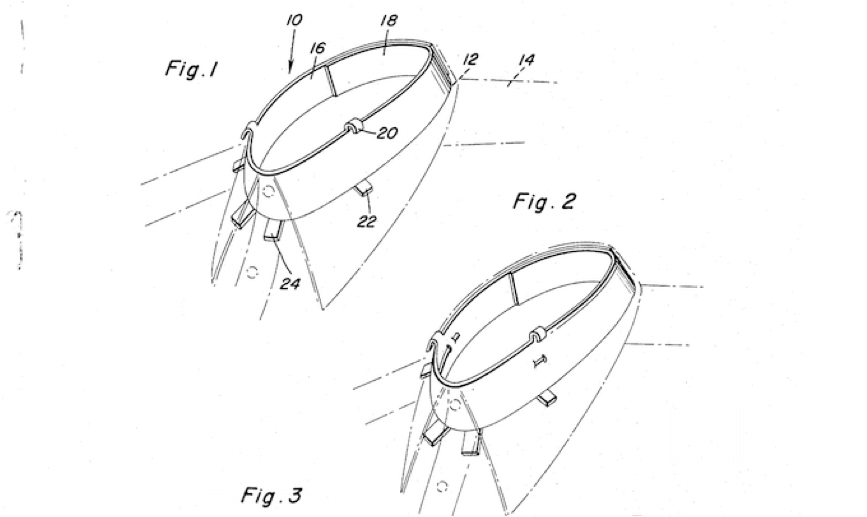

Though it has many cultural and stylistic incarnations – the mandarin, the wing collar, etc – the collar acts as a sort of sartorial point of entry for the body, or so Yohji Yamamoto describes it: ‘a most elegant means of creating an opening for the head’.

***

Further reading:

The white collar men are your clerks; they are your bookkeepers, your cashiers, your office men. We call them the “white collar men” in order to distinguish them from the men who work with uniform and overalls and carry the dinner pails. The boys over on the West side got that name for them. It was supposed to be something a little better than they were.

Malcolm McDowell for the Chicago Commerce, June 12, 1914.

Simply put, the work of a fashion designer is a battle with tailoring. During my first ten years making clothing I grappled with the idea of the collar – why does clothing need it? Is there no other way to handle that part of the garment? I was obsessed with the issue. When I began to work seriously on men’s fashion, though, I finally came to understand how the tailored collar was a most elegant means of creating an opening for the head.

If we consider the issue from the perspective of a craftsman and his technique, too, we find the broad opening responds to the needs. Imagine a rounded neckline open at the front. With a cloth draped around the neck, it simply makes sense to fold it back at the front of the garment. This is where the lapel originates, the neck is wrapped in the cloth, the portion in the front is folded back, where it comes to rest. With this, the collar as we know it is born. It is all perfectly natural.

What followed were variations on that theme intended to serve as protection for the nape of the neck or as ornamentation for the sake of appearances. Not all of this was a mere matter of detail, both the weight and presence of the collar itself had important roles to play. Without sufficient weight, the collar pulls away from the body, making the clothing uncomfortable. Leaving the nape of the neck exposed inevitably triggers a psychological sense of coldness. The tailored collar is indeed “a perfect monument” in the history of fashion.

Because the collar emerged from the natural relationship between the body and the fabric, it is not something that can be toyed with lightly. If we think of the collar as the ears, then the body must be constructed in the very same vein. If the body is of type A, then it simply will not do to have the collar be of type B. The white nun’s collar of classic clothing is like the white cloth draped over the top of the seats of the Shinkansen. As I see it, a basic collar is that which works with the natural flow of the material while that which interrupts the flow of the fabric is an ornamental collar.

If one studies a pattern for a collar one soon notices that it has a boomerang shape. Perhaps it is better thought of as resembling the gentle curve of a Japanese katana, or sword. When this curved item is bent, it attaches itself to the neck. This curve is the very lifeblood of the collar, and the arc must be infused with some tension. In the tiny area allotted to this feature even a few millimeters’ difference can bring out the distinctiveness or elegance of the collar.

The tension of that arc takes its life from its point of origin in the area of the neck. From there the energy flows quickly and directly, with no margin for error, in a straight line towards the top button. In this locus is contained the heart and soul of the tailored collar.

Beware! Do not take tampering with the collar lightly, it is not to be attempted until one has mastered the techniques necessary to survive a dues with traditional beauty.

Yohji Yamamoto on the collar, from My Dear Bomb, published by Ludion, 2011.