In a recent exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Art for the Millions: American Culture and Politics in the 1930s, curator Allison Rudnick assembled a range of works that characterise the decade as a time of social and political upheaval in the United States. Artists and designers responded to the changing world around them and created the visual and material culture of the depression era up to the start of World War II. The works included notable members of the canon of modern industrial and graphic design – Walter Dorwin Teague, Isamu Noguchi, Thomas Hart Benton as well as lesser-known but no less impressive creators like Ethel Dougan and Yolande Delasser. Consumer goods like newspapers, magazines, and posters were on view alongside fine art, and small-scale renderings representative of bigger federally sponsored programs. The stark and damning depictions of urban and rural poverty, labour unrest, and strident calls to collective action definitely felt more urgent than reflective. Leftist populism is more than a little out of the ordinary for the Metropolitan, making Art for The Millions a welcome change of pace.

Clothing was also in the mix, in the form of two dresses with textiles designed by Ruth Reeves and H.R. Mallinson & Co. Both have clean and simple silhouettes, designed to skim the body and not restrain it, with dynamic textile designs that spoke to the new woman of the time. Reeves was a successful woman designer, educated at the finest West and East Coat art schools, and studied in Paris under the painter Fernand Léger. Her 1932 carpet design still covers the Radio City Music Hall floors. The printed linen dress features her ‘Play Boy’ textile design where cubist-inspired active figures enjoy the sporting life. H.R. Mallinson & Co.’s silk dress from 1929 staked a claim to patriotic optimism right before the stock market crash. The design; ‘Betsey Ross/Liberty Bell’ from the Early American series is a dynamic composition with starbursts, soaring skyscrapers, and radiating beams of light in a colour palette that’s primarily black and hot pink. It stridently brings nostalgia for an idealised past into the twentieth century. H.R. Mallinson and Co. was based in New Jersey and founded by Polish immigrant Hiram Royal Mallinson, a skilled marketer who specialised in high-end, eye-catching designs. The two dresses effectively capture the style of the time, have strong ties to the artistic avant-garde, and are unapologetically modern.

Acknowledging that clothing is an essential part of the design idiom of this, or any historical moment, is significant. It’s refreshing to see fashion included in the conversation, at home with graphics and industrial design. But as much as the presence of these pieces, and representation of the designers and textile workers who created them was refreshing, it felt like something was missing. There is a disconnect between the garments and the other works. Specifically, in terms of the subjects represented in the other works. The sartorial equivalent of communist newspapers and posters championing the resettlement administration or rural electrification isn’t a Mallinson silk; it’s a pair of overalls.

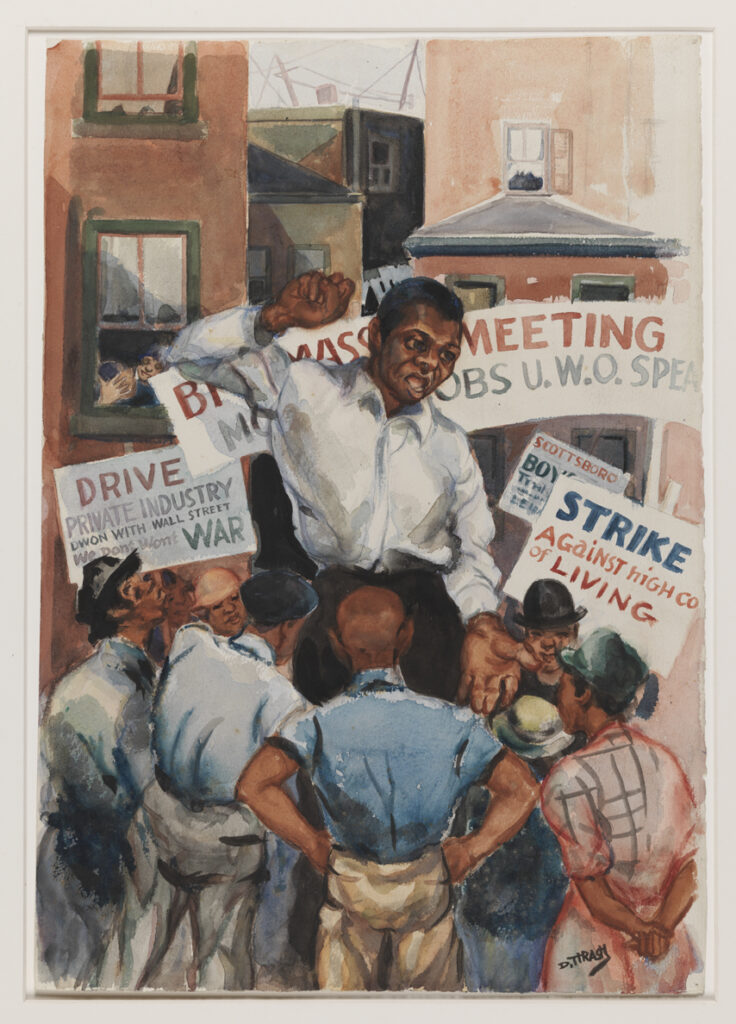

Overalls are both present and absent. The visuals offer an abundance of them – on the backs of farmers, builders, and strikers with sleeves rolled, pants cuffed. They’re also worn by the wrongfully

accused Scottsboro Boys, previsioning their symbolic significance in the civil rights movement.1 From Walker Evans’s photos of dust-bowl Alabama to riveters working steel-beamed New York City sky scrapers, overalls are the common denominator – the unofficial uniform of the American worker. Despite the visibility of overalls in two dimensions and its focus on art for the masses, the exhibition, like so many others, still adhered to elevated concepts of ‘art’ when it comes to apparel. It’s time collections and exhibitions begin to consider what work clothing, like overalls, can tell us about design and the people who wore them.

Simple, purpose-built work clothes are the products of American industry influenced by modernist aesthetics and manufacture as much as streamlined meat slicers or bakelite radios. Moreover, overalls were accessible and as close to gender neutral as a garment could be; women working in overalls aren’t as well represented, but they did wear them on jobsites and for domestic labour. Workwear was the product of mass manufacture of textiles, advances in large-scale dyeing, cutting, and sewing technologies, and the standardisation of sizing. All factory-made ready-to-wear fashion is, effectively, industrial design. But overalls with their uniform blue denim or hickory stripe, visible metal hardware, wide patch pockets, and loose fit that standardises the shape of the body by obscuring the features of the wearer, are the quintessential example of clothing as industrial design.

In his recent New Yorker article examining rural America in the national imagination, historian Daniel Immerwahr labelled the 1930’s ‘an overalls era.’2 This perspective is not just the result of hindsight, overalls carried symbolic weight in the early twentieth century as well. In 1920, when clothing prices, particularly men’s clothing prices, were considered to be too high, a short-lived but highly visible protest known as the Overalls Movement was born. Men across the country who wouldn’t have typically worn them to work, donned cheap overalls, jeans, and old clothes to communicate that, until clothing prices dropped, they would not purchase anything new. It was a popular demonstration that garnered vocal support from political and business interests. One St. Louis merchant expressed that: ‘the movement bore the stamp of real Americanism,’3 while a South Carolina senator admired the protestors mobilisation of the ‘simple costumes of their forefathers.’4 What’s telling here is the manner in which the overalls’ connection with work and the nation’s history seems tacitly accepted, and the garment’s communicative potential easily understood. The very real prevalence of workwear combined with its semiotic potential laid the groundwork for the visual culture of the 1930s that brought the visibility of overalls to new heights, thanks largely to the work of artists and photographers connected to the WPA and FSA who depicted agricultural and urban labour, many of whom adopted labourer’s clothes to work in themselves. By the early 1940s, critic John Kouwenhoven was part of a push to locate the roots of American modernism in vernacular design. Specifically, he looked to the simple and restrained construction of tools and machines that were improved upon by industrialisation as evidence of a ‘democratic-technological vernacular’ he considered unique to the United States.5 While he never extended his analysis to clothing, workwear garments like jeans and overalls wholly embody the concept of democratic-technological vernacular in fabrication, design, and in relation to the people who wore them.

Like all workwear, overalls were made by and for industrial labourers. The history of the textile and garment industries is the history of industrial capitalism; complete with all the innovation, exploitation, and abuses that entailed. Human craftmanship and automation were interdependent, and working people suffered the consequences of creative destruction that resulted from technological advancement. In response, their struggles set the standard in the battles for worker’s rights. Textile mills and garment factories were sites of some of the first large-scale labor organising. Such conflicts varied in degrees of violence and traced a timeline of manufacture, from the 1824 Pawtucket, RI cotton mill, Patterson, NJ in 1913, the garment factories of New York’s Lower East Side in the 1910s, to the ‘Uprising of ’34′ the largest strike in the nation that united 400,000 textile workers from northeastern and southern states. Labour unrest and organising efforts were impossible to ignore; communicated through publications like the Labor Defender and New Masses, and in artists’ depictions. The American worker of the 1930s is represented as simultaneously heroic and downtrodden; elevated as a champion of progress in one instance, scrapping with police on a picket line in another. Neither vision was exclusively true then, any more than it is now. Yet, the clothing worn on the backs of these same workers, the material output of the systems they toiled in and fought against, remains conspicuously absent and undervalued.

Art for the Millions is not devoted exclusively to fashion, and every collection has its limits. The Metropolitan is an art museum, and the collections reflect institutional values that highlight artistic excellence. The costume collection likewise envisions fashion as art and seeks the finest, technically astounding, creative examples, which historically aligns with the most elite and expensive. But perhaps it is time to reconsider these collecting practices. The museum, and its likes, holds examples of art and design consumed by the general public in the form of posters, magazines, postcards, and photographs. Maybe it’s time to consider the types clothing worn by millions of Americans as well? Including workwear would not diminish the impact of couture, the handcrafted, or the avant-garde. If anything, a sharecropper or factory worker’s overalls have the potential to enrich and expand the conversation around successful modern design, particularly because the garments are still with us. Overalls have changed very little in form or function since their inception. Fashionable adaptations notwithstanding, it’s an incredibly tenacious design. Effecting an immediate connection to museum objects, that relatability, gets more and more elusive with the distance of time. But it’s something that clothing, particularly everyday clothing, captures incredibly well.

Some recent fashion scholarship is helping to open the door. Hazel Clark and Cheryl Buckley’s Fashion and Everyday Life: New York and London (2017), and the anthology Everyday Fashion: Interpreting British Clothing Since 1600 (2023) cover a range of everyday garments and working people’s clothes. Exhibitions featuring workwear such as the aptly titled Invisible Men: An Anthology from the Westminster Menswear Archive in 2019, and last year’s Workwear at Rotterdam’s Nieuwe Instituut looked at the innovations in materials and design, past and present. Smith College’s recent exhibition and accompanying book, Real Clothes, Real Lives: 200 Years of What Women Wore, does an excellent job of closely examining everyday apparel, and even includes some women’s overalls. More work along these lines would do a lot to recalibrate fashion’s history; making it more inclusive and representative, but also to help reframe work clothes beyond social history to bring attention to the qualities of the designs themselves. The garments are out there too. While often, but not always, distressed from years of heavy use combined with little interest in conservation, there is a thriving global vintage market for workwear. Collectors are paying ever-higher prices for these rare items at auction, but cultural institutions have yet to step up.

A material connection between the subjects represented in the art and their apparel would have enriched connections to the 1930s, but workwear’s presence before and after this moment has the potential to strengthen a connection to visitors, and challenge us to reconsider the categories that limit our understandings of fashion, art, and design. Work clothes like overalls are a product of modern design with their own rich histories, worn by millions of people across the country and beyond. They deserve to be a part of the conversation; it’s long overdue.

Dr. Sonya Abrego is a New York City based design historian specializing in American fashion. She takes an interdisciplinary approach to examining the interconnections between popular culture, art, craft, and design. She’s the curator of Crafting Denim (2023), an exhibition for the Center for Craft in Asheville North Carolina, and her book, Westernwear: Postwar American Fashion and Culture (2022) is available from Bloomsbury.

Tanisha C. Ford, Liberated Threads: Black Women, Style, and the Global Politics of Soul, The University of North Carolina Press, 2015, p. 68 ↩

Daniel Immerwahr, ‘Beyond the Myth of Rural America,’ Oct. 16, 2023, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2023/10/23/beyond-the-myth-of-rural-america ↩

‘Even Overalls Sales May Yield An Honest Penny: If the Public Wants Overalls, We’ll Give Them What They Want, Is Attitude Some Retailers Are Taking,’ Women’s Wear, April 19, 1920: 1, p. 39 ↩

‘Women in Calico Join Overall Band: “Strike” Against High Price of Clothing Spreading Over the Country,’ The New York Times, April 17, 1920, p.1 ↩

John A. Kouwenhoven, “What is Vernacular?” in Made in America: The Arts in Modern Civilization, Doubleday, 1948. ↩