When Roland Barthes described the face of Greta Garbo as an idea, he was not only referring to its masklike qualities, but to the way it gestured to the mystical: ‘at once fragile and compact… not drawn but sculpted in something smooth and fragile, that is, at once perfect and ephemeral.’1 ‘How many actresses,’ he added, ‘have consented to let the crowd see the ominous maturing of their beauty? Not she; the essence was not to be degraded, her face was not to have any reality except that of its perfection.’ In 1957, when Mythologies, the book containing Le Visage de Garbo, was first published, Greta Garbo had been living more or less as a recluse for nine years. Increasingly, at the age of thirty-one and never having been particularly striking to begin with, it seems to me that she may have had the right idea. To age in public for a woman is, despite all woke societal efforts to the contrary, still hell; to age in public as a star is worse. We are living in an era, thank God, in which it’s acceptable to have a fifty-year-old female lead placed front-and-centre of your Netflix series, a la Renee Zellweger in What/If. We do not yet live in one in which Zellweger has not felt the need to surgically alter her face, however, so that the version of her onscreen both is and is not the Zellweger we remember. She is closer than she ought to be to youth, and further than she ought to be from actual nature.

Even younger stars, having committed the egregious sin of no longer appearing to be smooth and fragile, perfect and ephemeral, are brutalised. A roll-call of the sex symbols of my youth in the noughties – Britney Spears, Jessica Simpson, Lindsay Lohan, Megan Fox, Christina Aguilera – is notable for the fact that many of them dared to suffer what the tabloids saw as lapses in their promised hotness: weight gain, insanity, shaved heads and bad haircuts, cheap fake tans, bad plastic surgery, each mark against them more or less a problem auto-generated by the fact of being female, famous, femme and fuckable during a wave of (dubious, commercial) feminism that mistook the marketing of slogan thongs for self-empowerment. Britney, who only recently appears to be in spitting-distance of relinquishing her residency in Las Vegas, and who is not currently responsible for her own finances, is thirty-seven, making her a year older than Garbo was when she retired. In her videos on Instagram, she still looks gorgeous, bronzed, taut as a statue. She is flexible, still talented at dancing despite having suffered a knee-injury in 2004, and where she lives it looks like paradise. But isn’t she exhausted after all that work? Wouldn’t she sometimes like a vacation from being hot?

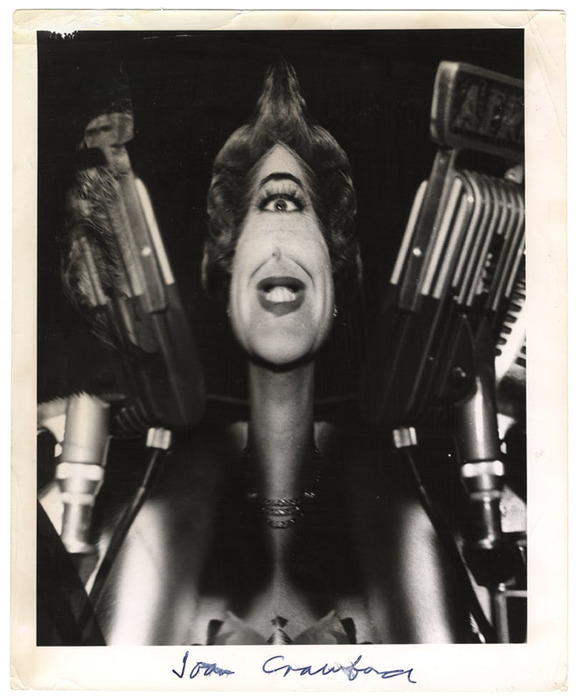

I have been thinking about beauty as a currency in women recently, especially, because I have been thinking about one of the all-time gamblers and investors in that currency, Joan Crawford. In comparison to her supposed nemesis, Bette Davis, Crawford was believed to owe her career to her beauty as a movie flapper, then to her aggressive sex appeal playing the mistress-bitch in women’s pictures. She was thirty-seven, too, when Garbo gave up public life in 1941, and had been working as an actress for almost two decades. She would never have considered quitting then, allowing audiences to see her maturing ominously until the mid-seventies, and she would never, not once, be described as ‘fragile’ or ‘ephemeral.’ Closer to the essential truth is the way that Barthes describes, in Mythologies, the new Citroen DS: as ‘the supreme creation of the era, conceived with passion by unknown artists, and consumed in image if not in usage by a whole population which appropriates [it] as a purely magical object.’2 ‘Joan Crawford,’ the New Yorker critic David Denby wrote in 2011, ‘[was] the prototype of the modern celebrity…who places herself at the vanguard of current erotic taste and thereby becomes attractive and slightly threatening at the same time.’3 Insensitive to tenderness and hypersensitive to imperfection, it was only logical that she would focus her attentions on being the best, the baddest, and the biggest bitch, a sex symbol too frightening and too abstract in her presentation to be (hetero)sexually appealing. If you want to see the girl next door, she quipped over and over, go next door, as if the die-hard fans she had in later life were interested in seeing girls at all.

It feels almost too on-the-nose that the ‘improved’ shape of her mouth was borne directly of disease. ‘After altering the shape of her face by having her back teeth removed to give her cheekbones,’ the Crawford biographer Shaun Considine wrote about a surgery she had in the late twenties, ‘the painful procedure…infected her gums, which stretched her mouth. When the swelling subsided, it left her with a larger upper lip. Pleased with the extension, she decided to paint in her lower lip, giving the world “the Crawford mouth.”’4 An alleged child rape victim and a casting couch regular so prolific that Bette Davis said she slept with ‘every male star at MGM except Lassie,’ it was not unusual for Crawford to take pain and spin it into an exaggerated, eroticised source of pleasure. ‘It has been said,’ she is supposed to have claimed, ‘that on screen, I personified the American woman.’ To believe that she agreed with this interpretation of her affect is to fundamentally misunderstand her vision; the way that she meant her looks to be interpreted like semaphore, worshipped like scripture. Always, she was meant to personify something better, something larger, than the American woman, something never more obvious than in the genesis and the evolution of the Crawford mouth.

Baboon-like in its signalling of sex and frightening in its scale, to look at it makes sense of Goethe’s claim that red, in colour theory, tends to exert a ‘grave and magnificent effect.’5 At twenty-four, as what F. Scott Fitzgerald called ‘the best example of the flapper,’6 her lips were two afterthoughts around a dazzling set of teeth; just four years later, they were wider, thicker, turned by Max Factor’s aforementioned technique ‘the smear’ into something resembling the waxy, bright red candy mouths they sell in joke shops. By the time she had turned thirty, they were as iconic and as non-negotiable a part of her self-image as the sweeping, cathedral-like bones of her singular face. By the time she appeared in Johnny Guitar, at the age of fifty, they were more paint than biology, her face pre-emptively resembling that of a male Joan Crawford impersonator. ‘Never seen a woman who was more a man,’ a bartender says about her character, a tough, butch bitch who owns a tavern. ‘She thinks like one, she acts like one. It almost makes me feel I’m not.’ It’s true that like a man, Joan Crawford turned her fury and her suffering outwards as she hit impotent middle-age, projecting an eroticism that made sex seem like a war, and sexual partners like opponents. Like a man she did not not care to hear ‘no,’ did not hear it gracefully. Increasingly, her mouth was war-paint. ‘For Joan Crawford, her cosmetics were not negotiable,’ wrote Donald Spoto in Possessed, referring to her image in the fifties. ‘As in years past, she again regarded the thickly arched eyebrows and over-the-lip gloss as an infallible sign of female desirability, and no director could shake her from that imprudent conviction.’7

‘[In Johnny Guitar], she is beyond considerations of beauty,’ François Truffault said. ‘She has become unreal, a fantasy of herself. Whiteness has invaded her eyes, muscles have taken over her face, a will of iron behind a face of steel. She is a phenomenon. She is becoming more manly as she grows older. Her clipped, tense acting, pushed almost to paroxysm by [director Nicholas] Ray, is in itself a strange and fascinating spectacle.’8 The spectacle became stranger, more fascinating, with each passing year, the Crawford mouth developing into a logo as distinctive as a Pepsi Cola label. Her self-image, increasingly baroque and recursive, became more recursive still as she began to play glamazons undone by their age: a former actress in a wheelchair, a maniac with an axe. The thought of being ‘beyond beauty,’ as Truffault said, did not present itself to her as an opportunity for anonymity or for reflection; only as a kind of half-death before death. If she could no longer be the divine Joan Crawford, it was clear that she would not return to being little lipless Lucille out of San Antonio, Texas, daughter to a housewife and a laundry labourer, step-daughter to a pervert. ‘I’ve been asked if I ever go around in disguise,’ she wrote in 1971, in an advice book called – as if it were a gospel delivered from on high by The Prophet Joan – My Way of Life. ‘Never! I want to be recognised. When I hear people say “that’s Joan Crawford!,” I turn around and say “hi, how are you?”’9

Crawford is a case-study in beauty capital gone bad: an ingénue, and then a sex symbol, and then a calcified image of what she believed a sex symbol ought to be, both immovable and outdated. Her beauty routine became a ritual designed to keep the desperate Texan wolf, Lucille, from her filigreed mansion door, just as Monroe’s was meant to stave off Norma Jean, or Britney Spears’ was meant to keep her from returning to being Britney Jean of Kentwood. As it turned out, fearing Lucille’s ghost proved pointless – three decades of Joan had more or less succeeded in erasing her from Crawford’s mind, the outcome being that in private she had no idea how to behave, no idea of her own desires or opinions. There were no lapses, no moments of ill-advised authenticity. By the mid-fifties, she was dressing as Joan Crawford to take out the trash, announcing ‘hello, this is Joan Crawford’ when calling up the operator, opening her fan mail in gowns specially designed for answering Joan Crawford’s fan mail. In an era when to do so was not de rigeur but unthinkably gauche, she regularly called the paparazzi. ‘No one decided to make Joan Crawford a star,’ the MGM screenwriter Frederica Sagor Maas once said. ‘Joan Crawford became a star because Joan Crawford decided to become a star.’ ‘In some ways,’ she admitted, ‘I’m a goddamn image, not a person.’

It takes talent, nerve, and an unfaltering sense of self for a middle-aged famous woman to grow into an authentic and imperfect late-middle-aged famous woman. When Laura Dern said to The Guardian this summer that ‘my kids know I want to move to Paris, [because] when I’ve still not done face work at seventy, there will be directors there who will hire me and we’ll get to explore while allowing me to be my age,’10 it is possible that she was thinking of Isabelle Huppert, who at sixty-six and with what can only be minor work still looks more or less like a sixty-year-old version of herself, and whose imperious, intimidating face still moves with the elastic ease it did at thirty, or at forty, or at fifty-five. ‘I don’t feel old, and asking women about ageing is very negative,’ Huppert told the same newspaper two years earlier. ‘It doesn’t concern me; it’s other people’s problem, not mine… I am far too lazy to exercise. I hear yoga is good and I may try it one day but I prefer to sleep.’11 Laura Dern, at fifty-two, is still one of the best American actresses of her generation, a performer who transmutes what should be melodrama into something realer and more tender, and who improves year by year, project by project. Like Huppert, she had always had sex appeal, a face not easily mistaken for another face. Unlike, say, Nicole Kidman, she did not have the tremendous load of being one of Hollywood’s great beauties, its elite wives and prime GQ cover models, on her shoulders; accordingly, it is only recently that Kidman, easing on her use of fillers, has begun to turn in great performances again, unfrozen as if by a benign spell.

Once the spell is undone, it may be difficult to look back on the years spent sleeping. Jane Fonda, also marred in early life by bad behaviour from a father figure, first buried her intellect in order to make films like Barbarella, and then allowed her repressed rage to explode pell-mell by turning into Hanoi Jane. It took her until she was forty-five to conquer her bulimia and anorexia, and until she was in her seventies to realise that her ideas were intriguing enough to withstand the fact that she no longer looked like Barbarella in the photographs accompanying her interviews. ‘I’m glad I look good for my age, but I’ve had plastic surgery, and I’m not going to lie about that,’ she offered in the documentary Jane Fonda in Five Acts. ‘On one level, I hate the fact that I’ve had the need to alter myself physically to feel that I’m OK. I wish I wasn’t like that. I love older faces. I love lived-in faces. I loved Vanessa Redgrave’s face. I wish I was braver. But I am what I am.’ Garbo, choosing to retire at the peak of her desirability, bought low and sold high. Other stars, afraid to sell at all, gamble until the thing they’re betting loses value. The house, if we are to think of Hollywood as a casino, always wins. The stock market, if we are to think of it as a stock market, does not always pay dividends.

‘[Joan] Crawford’s whole professional life has been one of great concern with her person,’ the photographer Eve Arnold wrote, recalling a collaboration with her in the fifties. ‘It is a commodity which she sells not only to the public, but also to herself.’12 In the last shoot she ever did, in 1976, Crawford is all eyes and mouth and eyebrows, like a version of Joan Crawford drawn from memory on a telephone pad. Still, she is iconic, more woman than woman, and more star than star. Lensed softly, she glows like a make-up mirror. What is notable in her last year of life is the relative subtlety of her lip colour, which no longer looks deep red or bloody, like a cannibal or a mean clown, but like the lipstick of grand dame: light pink, coral-ish, designed to flatter pallor. Two years earlier, at the Rainbow Room in New York, she had made her last public appearance as Joan Crawford, recovering from extensive, painful dental surgery, and looking roughly her real age. ‘If that’s the way I look,’ she reportedly said on seeing photographs of her and Rosalind Russell in the morning paper, ‘then they’ve seen the last of me.’

She meant it – three years of reclusion followed, later by far than they were for Garbo, meaning that we had already seen what Crawford had become. Whether her retirement from public appearances had been for her, or us – whether her aim was to relieve herself of the unkind attentions of her public, or to sacrifice herself in order to relieve us of the sight of her deterioration – was unclear. What was clear was that in the photographs of her taken the year before she died, the same conceptual certainty ran through each picture like a melody with a familiar tune: that of the star who orchestrated her self-image into inhuman oblivion presenting herself the way she would like us to remember her. She did not want us to forget the version of her we had dreamed into existence after seeing her onscreen, in publicity photographs, in paparazzi shots where she was doing nothing much but still dressed as if for a premiere. She wanted us to think always of Joan, and not Lucille. The mouth, less furious and less outré than before, spoke without actually speaking. It said: think of me the way I was, forever.

Philippa Snow is a writer based in Norwich, England.

This article was originally published in Vestoj On Capital, available for purchase here.

R Barthes, Mythologies, Les Lettres Nouvelles, 1957. ↩

Ibid. ↩

D Denby, ‘Escape Artist,’ The New Yorker, January 2011. ↩

S Considine, Better & Joan: The Divine Feud, Graymalkin Media, 1989 ↩

J. W. von Goethe, Theory of Colours, John Murray, 1810. ↩

D Bret, Joan Crawford: Hollywood Martyr, Robson Books, 2006. ↩

D Spoto, Possessed: The Life of Joan Crawford, William Morrow, 2010. ↩

D Denby, ‘Escape Artist’, The New Yorker, January 2011. ↩

J Crawford, My Way of Life, Simon & Schuster, 1971. ↩

A Hicklin, ‘Laura Dern: “I feel like I’m ready to try anything — and to dive deeper,”’ The Guardian, June 9th 2019. ↩

E Cook, ‘Isabelle Huppert: “I may try yoga one day, but I prefer to sleep,”’ The Guardian, June 24th 2017. ↩

E Arnold, ‘Joan Crawford: A Public Image,’ Magnum Photo, May 10th 2017. ↩