In 2014, a woman posed a question to the 1.1 million members of a Reddit thread called Female Fashion Advice. The post was titled ‘Help, I need to wear an ID badge/key card at work!’and it was right in between ‘Help! Uniform for conference interns’ and ‘Enamel pin badges — how do you wear yours?’ How, she wanted to know, do you wear an ID without messing up your outfit?

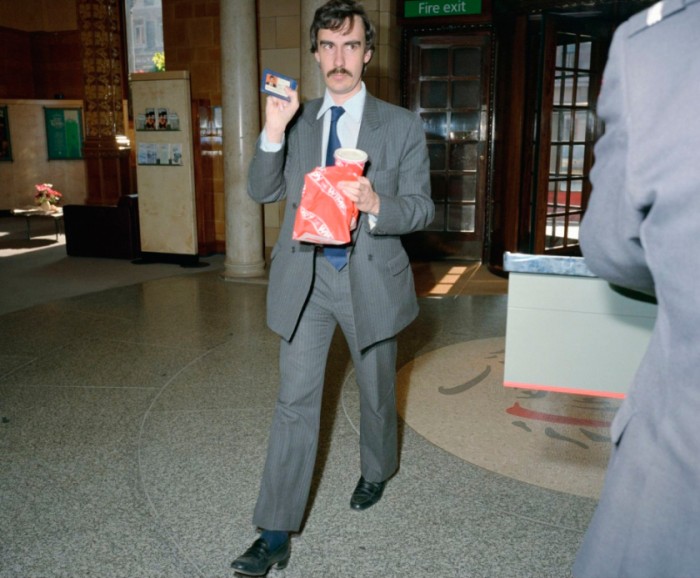

Each day millions of people — a veritable army — put on an ID badge and go to work. The badge is usually a plastic card clipped to a lanyard with a photograph that looks like state-issued documentation.

Forty-three of them were quick with a reply: carry a purse, a phone case with card slots, use a retractable badge, hang it on a silver necklace like the one the commenter’s mother wears.

In design parlance this is known as a workaround. When people hang jackets on doorknobs, write PIN numbers on their hands and chain bicycles to park benches, says designer Tim Brown, the adaptation reveals an unmet need.1 On Reddit, the tone was supportive and friendly. Everyone agreed it was a pain, but a necessary one. If the ID badge is a collective fashion problem, and the Reddit thread suggest that it is also, by turns, a status symbol, an ergonomic challenge and a proxy for the changing nature of work. As with any other aggravation, from ugly smoke detectors to hidden security cameras, millions of people have, in their own ways, learned to deal with it.2

The lanyard was once useful — it originated as an accessory to war. Everything from badges and lanyards, worn at work, to camouflage, worn worldwide, to food pouches, now feeding babies globally, was developed by the military. In its first incarnation it was a strap made of rope, threaded through hooks to rig sails or attached to a knife or a whistle. Early news references to lanyards often involved wartime activity. ‘Early Bradley Pulls First Lanyard as All American Artillery Pieces in France Hurl Steel Against Germans’ Positions,’ reads a New York Times headline from 1944. One pulled, but did not wear, a lanyard.

But our badges serve the same purpose as they do in the army. Agreeing to wear them is an act of ‘consensus essential to community life,’ like using hello as a greeting.3 The badge stratifies, keeping its wearers in and others out. At Davos, for example, where heads of state and celebrities meet to discuss global affairs, the badge system is colour-coded and complex. Different shades denote varied levels of access, which sometimes results in paranoia. ‘Every encounter begins with an unabashed glance or two down at the other’s badge. It is Davos Man’s defining gesture,’ writes Nick Paumgarten of his time there. ‘So frequently did gazes slip to reexamine my badge that I came to know what it must be like to have cleavage.’4

Employees express the same kinds of feelings. A Google contract worker described her disappointing badge on Forbes like this: ‘This may seem like a silly thing…but never has something made me feel like I stood out more in a workplace. Google employee badges are 3D and have the standard picture along with different colored bubbles. The contractor badge had the standard picture and a very obvious red background, not to mention starting out with the big red C, which we nicknamed the scarlet letter.’5

So what of the lanyard of the future? The system that created the lanyard is a system predicated on the fragile thesis that people don’t mind wearing plastic tags around their necks when they leave the house. But the remote worker, who is the worker of the future, doesn’t need a badge. They were designed for the workers of the last century, who never left their desks. Workers are now untethered, meeting in communal spaces or a warehouse in Brooklyn. They have standing desks and walking meetings. Their phone is the office they carry with them.

Where we work, and how we feel about it, has also changed in the last decade. In 2005, Enron book-ended the dot com bubble. The first episode of The Office aired. Two years later, Joshua Ferris published Then We Came to the End, a bestseller about corporate culture, and Matthew Weiner created Mad Men. Work became a setting to explore alienation and anxiety, and revealed a cynicism about how it might set us free.

The very idea of identification has changed along with it. We’re being surveilled in more ways than ever before. Fingerprints and eye scans are replacing photographs. There’s a laser that can track a heartbeat. Technology, and identification, is binding itself to our bodies in irreversible ways. Sociometric badges were once used to monitor and track office behaviour in a scientific study and people found it creepy. But worrying about a badge that gathers data now seems quaint since we worry about being tracked online and on the street. If ID badges suggested there was a freedom to the twenty-first century office, a boomeranging ease to come and go as we pleased, this new kind of identification signals its end.

Jordan MacInnis lives in Toronto, and works as a writer and in PR.

T Brown, Change By Design, New York: HarperCollins, 2009, p. 40–41 ↩

B Katz, Make It New: The History of Silicon Valley Design, Cambridge: MIT Press, 2015, p.178 ↩

U Eco, Travels in Hyperreality, San Diego: Harcourt, Brace & Company, 1986, p.177 ↩

N Paumgarten, ‘Magic Mountain,’ The New Yorker, March 5, 2012. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2012/03/05/magic-mountain ↩

Quora Contributor, ‘What It’s Like to Work at Google as a Contractor,’ Forbes, September 24, 2014. https://www.forbes.com/sites/quora/2014/09/24/what-its-like-to-work-as-a-google-contractor/#296983737ac9 ↩