What one wears to the dinner party of a Mongolian khan-emperor can be a perilous decision. The host has just conquered half the world — it may be imprudent to challenge his dress code. But in 13th and 14th century Mongolia, meeting the imperial standard was no easy feat: the banquet’s requisite zhisun robe was woven of actual gold, studded with pearls and gemstones.1 It was doubtless a tad expensive and perhaps also just a tad bit heavy.

Research today on surviving examples of the zhisun is the opposite: it’s quite light, which is unfair.2 This seldom studied silk ensemble was revolutionary in its day. Now it stands as a small, handcrafted gateway into not only the Mongol past, but also into our globalised present.

The zhisun was skirted and long, tight-sleeved and tight-waisted. Royal versions were colourful, brocaded all-over, and, as might be imagined, surely dazzling among all those silken tents and glowing torches set up for an evening feast on the Eurasian steppe. Khubilai Khan, grandson to the more terrifying Chinggis (Genghis) Khan, had his summer capital built a short 860 kilometers north of modern Beijing. The vast riches of the whole Mongol Empire would have been on display there for such summer parties. Around the imperial family and their guests, the steppeland’s rolling sea of endless grass would have stretched on as far as the eye could see — a natural visual allegory for the Empire’s great reach.

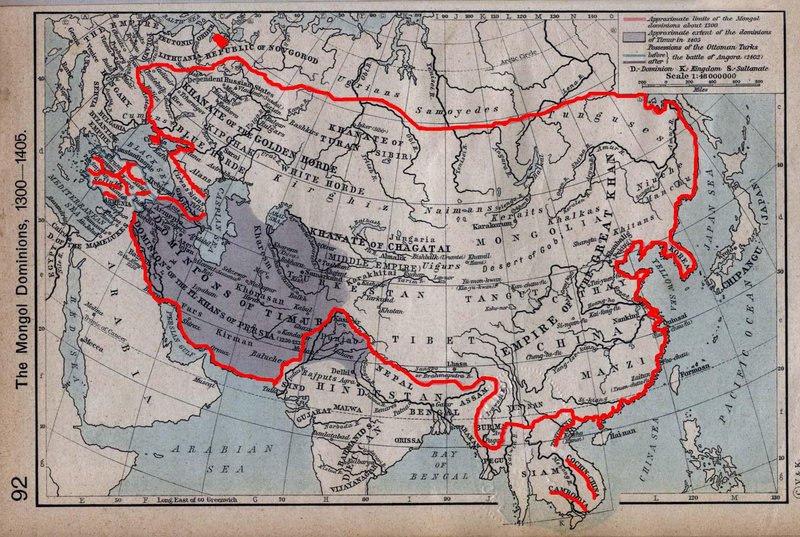

Khubilai directly ruled over just one part of the larger Mongol confederation that ran from Korea to the Danube in Europe. His relatives lorded over those pieces farther west: the Chagatai khanate in Central Asia; the Ilkhanate in Persia and into modern Turkey; the Golden Horde in Eastern Europe, the Caucasus, Russia. But Khubilai’s piece was the richest. He, the Great Khan, had China. There he founded his Mongolian-led Yuan dynasty in 1271.

The Yuan lasted about a century, but the dynasty still resonates today in the twenty-first century as we grapple with similar currents of globalisation. Geographically, with their horses, trade routes, and a medieval postage system, the Mongols linked up Eurasia in more ways than ever before. Temporally, their empire sat abreast of groundbreaking technologies: printmaking, gunpowder, cannonfire, plus tea and high-fired porcelain that grew to fuel maritime trade to global markets.3 It was the era of Marco Polo. It was the world of the Silk Roads. Our own present day might be dubbed the moment of 5G and AI, or the small, small world of affordable air travel and Amazon dot com. Connection, trade, newer and better technology, the list of parallels goes on. And despite this year’s blip of coronavirus, globalisation will go on, too.

For a nomadic society like the Mongols, lightweight, foldable, multi-use textiles represented the most practical way to showcase, store, and transport wealth. The textile of choice was Chinese silk. It could be worn. It could be traded. It was used for tents, for bags and travel, for blankets, for a makeshift floor spread out atop the steppeland grasses. Silk is also a protein fibre: like wool or fur, it is durable, warm, quick to dry. This tenacity against the elements matched silk’s versatility in larger artistic processes of brocade, embroidery, appliqué, tapestry and painting.

Silk textiles reached a level of importance such that Khubilai and his queen, Chabi, renewed a process first begun under the khans in the early 1200s: they forcibly relocated craftsmen from all corners of Eurasia into production centres nearer to the imperial wardrobe. Herat in Persia was one key source of weavers, as was Samarkand in today’s Uzbekistan. Beshbaliq in the Uighur vassal state of Qocho (today’s Chinese Xinjiang), sent hundreds of skilled artisans to regions around the main Yuan capital in Beijing. The most brilliant fabric in production was nasij — the cloth of gold.4

A neutral silk gauze acts as the ground weave in nasij. It is the structure. Overlaying it, concealing it, are designs and patterns woven from silk threads individually wrapped, one-by-one, in paper or even leather that has been painted with gold leaf. This is the fabric of the royal zhisun, the imperial banquet dress and a costume of Yuan court.

No intact, royal-class zhisun has been located, but textual references abound and scraps of nasij fabric have been uncovered in tombs. Surviving paintings also depict Mongolian aristocrats wearing such gowns in formal portraits and even hunting or sports scenes.

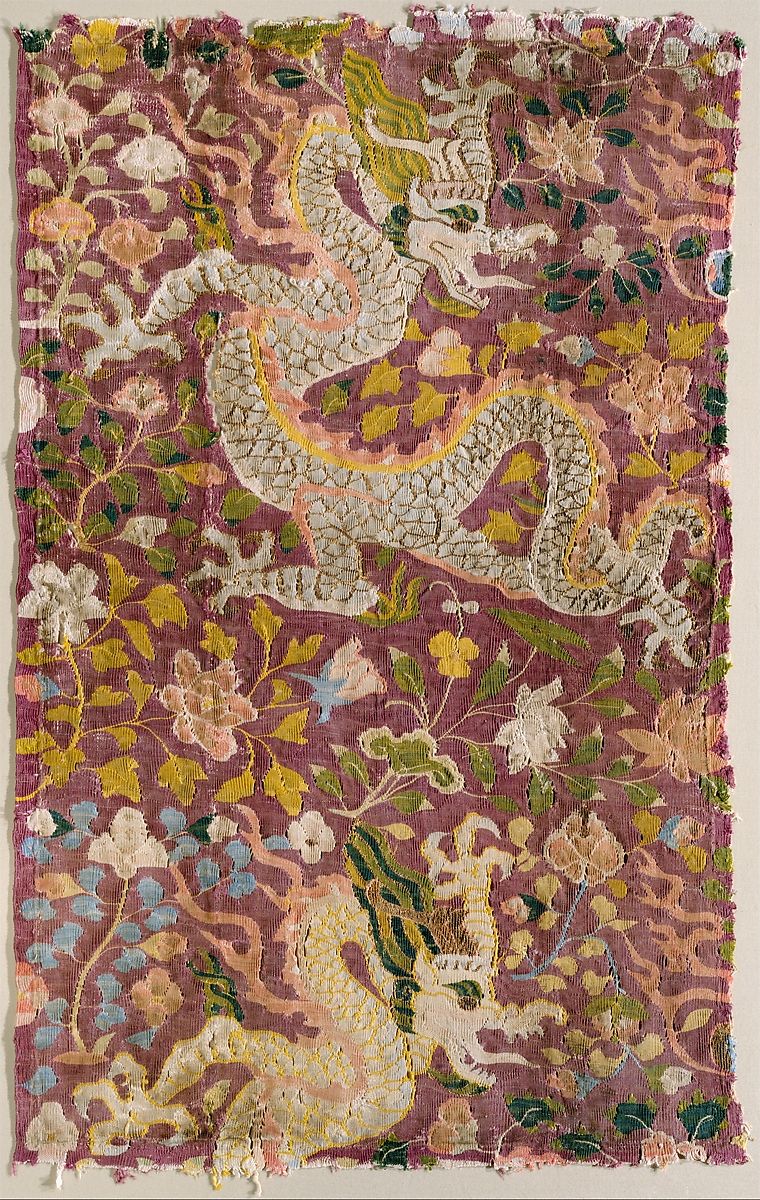

Broken down, the nasij-woven zhisun is the hallmark of Yuan China’s transcultural experience. The high technical skill evidenced by existing nasij samples, plus their frequent use of that other Chinese invention, paper, suggest a government-sponsored workshop where Chinese weavers worked alongside Persian and other Central Asian transplants. The winged, paired lions and griffins on the example here — the former’s wings decorated with Chinese cloud design — are foreign motifs in China; their origin lies to the west, in the Persian cultural sphere.5

Yet even so, replace these creatures with the iconically Chinese dragon and the foreign influence still has startling effects.

This silk tapestry, a Chinese kesi, was found in Central Asia and dates from the 11th or 12th century. Artisans in Bukhara or Samarkand or some other Silk Roads city had mastered the kesi and the Chinese dragon, but they now placed the beast atop their own Central Asian, groundless field of flowers and foliage. The un-grounding of the dragon, which was normally very fixedly attached as a handle on ceramic or jade, or otherwise given some sort of surface to perch and crawl upon — it evokes a weightless quality, a mood of flight. The airborne dragon can now twist and turn, coiling and uncoiling. He is also masculinised with an added beard, a stockier snout (perhaps adopted from depictions of the Indian giraffe), and he has been given much more thickness and muscle. The dragon is shifting from its age-old Chinese signification as an auspicious guardian or bringer of good fortune into a symbol of authority, a projection of strength and power.6

This groundlessness readies the dragon for greater textile deployment, especially within the imported Persian roundel. The Mongol Yuan adopted wholesale this repeat pattern of often mythical beasts folded into repetitious pearl-like windows (see the nasij sample above). The roundel can be found even on the inner flaps of this more common zhisun from the 13th century.

The dragon-in-roundel is now a talisman, an authoritative signifier of power and strength worn by the khan and his elites. The un-grounded beast can appear anywhere at any time. There’s an implied omniscience and omnipresence that matches the Mongol Yuan’s martial prowess, their horseback armies appearing atop a distant hill on the steppe, demanding submission or else bringing annihilation.

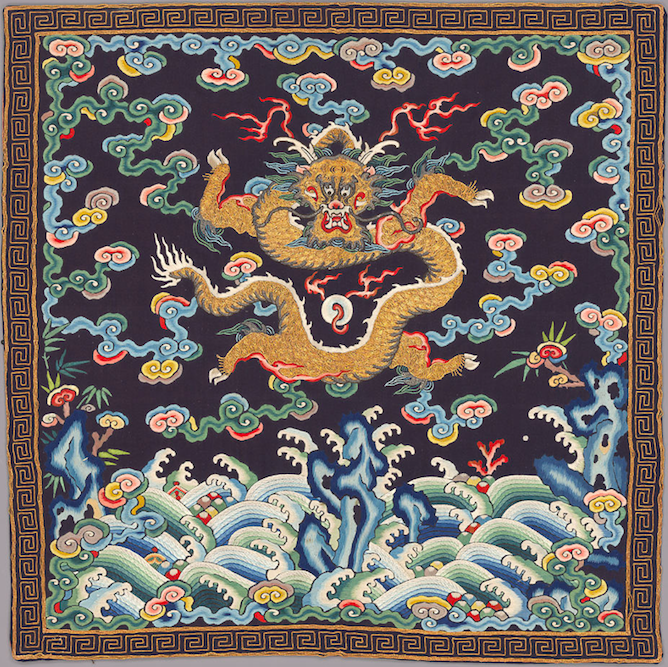

The Yuan zhisun amalgamated diverse visual motifs and complex textile construction techniques, doing so through processes of both subtle cultural diffusion (the spread of the dragon or the griffin motif) and state-directed exchange (the forced relocation of craftsmen). The zhisun also altered later fashion trends in its host country of China. In a nod to the Mongol tradition, the rulers of succeeding Ming (1378-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties kept their sleeves tight — all the better to ride a horse or shoot a gun or bow and arrow. These later dynasties also birthed what’s labelled in museum exhibitions everywhere today as the imperial Dragon Robe. The compacted dragon, now given real power and authority, takes flight emblazoned across the emperor and empress’s silk attire — a talisman of the imperial right to rule, a decorative symbol restricted to exclusive use by royalty and titled aristocrats.

Textile art perhaps went further during the Yuan than during any other Chinese dynasty. For the first and last time, imperial portraiture was done in silk tapestry in addition to being painted on scroll or mural. And the dragon robes described above may be linked to a Mongol convention of brocading detailed scenes as a large badge across the chest or back of a zhisun. Today these are commonly called ‘mandarin squares,’ more well-known for their use by the Ming and Qing to designate rank or status.

The present moment is very much engaged with how to classify, label, term, and study the Mongol and Yuan periods, as well as the multifaceted histories of the Eurasian Silk Roads.7 The way in which these subjects capture ‘the core issue’ of our globalised world, which might be termed ‘the dialectical relation of particularism and universalism’ — or in our case here the relation between a Mongolian style of dress and the larger 13th-14th century Eurasian zeitgeist — is captivating.8 These discussions greatly expand ideas of transculturality.

Decentring fixed notions and dichotomies can be the first step in initiating transcultural discussions, and doing so acknowledges the interdisciplinary nature of transcultural, globalised study. History and art history, archaeology and material studies and visual studies — all of these go hand-in-hand when disassembling dishonest labels of ‘pure’ or ‘original’ or ‘national.’ In this way the broader realisations of hybridity, influence, or exchange can shine through.

The Chinese dragon is Chinese, but how did it become so? And what does ‘Chinese’ even mean in the context of a transcontinental empire from the 1300s? What does it mean today? Is the Mongolian zhisun simply that — Mongolian? A much more interesting line of questioning is how these constructions of silk and gold came to transport so many images, symbols, cultures, and narratives.

And such pursuits are not just endless streams of theoretical deconstruction or archaeological sleuthing up and down the Eurasian steppe. These trails can end in present-day answers that address present-day concerns. One prescient example is the soft but steady confrontation such intellectual efforts offer to the alleged cultural, political, and physical assault taking place today against the Uighur community in Xinjiang, in the geographic heart of the old Silk Roads. Just as many Uighurs were once forcefully relocated by the Mongol elite, so, too, is the current population being intentionally scattered about in factories and labour camps where they produce everything from apparel to coronavirus PPE.9 Just as Mongol nobles once fretted over what to wear to the imperial banquet, so, too, must we worry about what we wear and where it comes from.

Tracking down and dismantling narratives of cultural purity or ethno-nationalism, even unto their deep historical roots, has never been more important. For it is these narratives that enable the darker elements of globalisation.

Walsh Millette is a graduate student at Peking University studying Chinese history.

Joyce Denney, ‘Mongol Dress in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries.’ In The World of Khubilai Khan: Chinese Art in the Yuan Dynasty, edited by James C. Y. Watt, 74-83. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2010. ↩

Patricia Buckley Ebrey, and Shih-shan Susan Huang. ‘Introduction.’ In Visual and Material Cultures in Middle Period China, edited by P. B. Ebrey and S. S. Huang, 1-37. Leiden, Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill, 2017. ‘Scholarship on the visual and material cultures of the Middle Period is already quite substantial. Some time-honoured topics, such as connoisseurship, landscape paintings, court art and politics, and connections to the art of Korea and Japan continue to attract scholarly endeavour and yield new results. Architecture and textiles, which had been somewhat neglected, are now being reconsidered as visually powerful material’ (p. 7-8). ↩

James C. Y. Watt, and Anne E. Wardell, ‘Introduction.’ In When Silk was Gold: Central Asian and Chinese Textiles, 14-19. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1997. ↩

Joyce Denny, ‘Textiles in the Mongol and Yuan Periods.’ In The World of Khubilai Khan: Chinese Art in the Yuan Dynasty, edited by James C. Y. Watt, 241-267. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2010. ↩

James C. Y. Watt, ‘The World of Khubilai Khan: Chinese Art in the Yuan Dynasty — A Retrospective.’ 2010. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Video lecture, 47 minutes. Available from: https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2010/khubilai-khan ↩

Keith J. Wilson, ‘Powerful Form and Potent Symbol: The Dragon in Asia.’ In The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art, 286-323. Ohio: The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1990. ↩

For more on this, see Richard Vinograd, ‘De-centering Yuan Painting,’ in Ars Orientalis, 2007, vol. 37, 195-212, or Sonya S. Lee, ‘Recent Publications on the Art and Archaeology of Kucha: A Review Article,’ in Archives of Asian Art, 2008, 68:2. ↩

Cheng-hua Wang. 2014. ‘WHITHER ART HISTORY? A Global Perspective on Eighteenth-Century Chinese Art and Visual Culture.’ The Art Bulletin, pp.379-394. ↩

Jen Kirby, ‘Concentration camps and forced labor: China’s repression of the Uighurs, explained.’ Vox. July 28, 2020. ↩