WHAT IS A WORSE insult for the American man than being called a ‘suit’?

The etymology of the word is itself a sad-sack Mad Men meme: sute, from 1300, both ‘a band of followers’ and a ‘set of matching garments;’ suite and sieute, from Old French, ‘assembly; act of following;’ evolving to suit, which means to ‘be agreeable or convenient,’ from 1570 (to be ‘unsuited,’ in contrast, is to be ‘unfit’).

A suit is a tortured Don Draper in New York greys, not yet aware of the liberated fruit the bohemians in Los Angeles have found, tie knotted to brutal perfection. Just as with our bafflingly stubborn sartorial romance with the great American cautionary tale The Great Gatsby, Mad Men’s depressing suits became a defining aesthetic of the downtrodden near-Depression of the late-2000s. It is as if Americans, in flaunting our willful misunderstanding of the failure of the American Dream, believe we can somehow always get it back.

A suit is a man defined by work, which is to say by the rituals attached to the acquisition of things so as to attain more things: he is a rule-follower and the worst kind of boss; primed for a Cheever-like midlife crisis, tied to the capitalist ritual of adulthood like he is to the commuter train schedule or the e-mail alerts on his phone. Sometimes, a suit doesn’t even care if the suit fits. That’s the saddest kind of suit of all. And yet!

A suit isn’t merely a uniform, traditionally made of one fabric. It is, if one is a believer in the power of style, a sly opportunity to play with notions of passing while also signaling dissent.

Witness: The gentleman my girlfriend and I saw sitting on the steps of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Manhattan one Sunday this summer. I clocked him as at least sixty-five, and possessing the cool confidence and flamboyance of an Italian on holiday. He wore a fitted, elegantly deconstructed jacket and matching trousers in a light grey that matched his neatly groomed salt-and-pepper beard; a crisp, unbuttoned white shirt; Persol sunglasses; and beat-up white high-top Vans. His style was a kind of riff: a love letter and a middle finger to a bygone masculinity.

Because what is more symbolic of the performance of being a man than a suit? Most rites of passage still require one. The suit I wore to my mother’s memorial service was a light grey Ludlow from J. Crew, the same suit I’d worn to my brother’s wedding a few months earlier. It was the first one I ever bought off-the-rack, in a pinch back when I lived in Boston and did a brief contract gig writing copy about regional parks for the state website, a time I mostly remember as an endless search for adjectives.

I began injecting testosterone at thirty. When I slipped on the jacket in front of the mall mirror at thirty-two, I beamed. Tattooed, with a little hard-won stubble, I could see my contrasts cleanly, my aesthetics an armour telegraphing a history beyond words. A prison for some men was, for me, a church: the rare and precise glory of an integrated self.

All summer, I experimented with being a suit. (I admit that my tolerance for uniforms may be higher than most. I once spent four months wearing only black T-shirts, an exercise that exhausted and enlivened me.) It was a perfect storm: my boss, an actual Suit, was a bad-breathed tyrant who seemed to have modeled himself off the villain in Office Space. He slumped by regularly to check my work, his black Brooks Brothers jacket boxy and always a little greasy, as if he used it as a napkin in a pinch. The cubicles required us to sit with our backs-out, like a bureaucratic panopticon, and my co-workers, many of them near-retirement, spent most of their days finding creative ways to torture The Suit, who reminded us often that he came from IBM. It was into this concrete fortress of bad vibes that I’d arrive on Mondays with a steaming cup of Dunkin’ Donuts. I was early in my transition and had a glow of boyishness I lost when I grew a beard, but it was hard to wear the suit with the kind of authority that I’ve since learned makes a suit more than a uniform, but a statement.

But I learned to walk differently that summer. I went to a barbershop in Back Bay every two weeks, and discovered the small joy of a pocket square, and the many nuances of a tie. When I moved to New York that autumn, I hung up my suit for a string of jobs in digital media, where a new uniform had cropped up, a casual response to the buttoned-up worlds most journalists have left behind. In the age of the Zuckerberg hoodie, a suit at work now feels more truly reserved for Suits, those among us still working for companies without flex-time and paternity leave and ping-pong tables in the lobby.

Recently, I showed up to work in a bright blue summer suit with a white shirt, no tie, and new brown brogues. I was attending a mayoral gala that night, and didn’t have time to go home and change. The effect was tremendous: co-workers kindly complimented me, but also treated me differently, like an elegant artefact, an object of celebration, a mysterious animal deserving of a gentle respect. My hand tattoos popped beneath the cuffs of the jacket: a lion on my right hand, a lamb on my left. I felt handsome, and like a ghost of myself, and like myself.

I’d bought this latest suit the same weekend this summer that I saw that Italian guy on the cathedral steps. As I took the train to meet my girlfriend, I remembered her pointing to him, and the sense of recognition that passed through me as I glanced his way.

‘That’s you in thirty years,’ she said, and I grinned. I’d never felt more seen.

Thomas Page McBee was born in North Carolina and, according to his birth certificate, became a man at age thirty-one. His memoir Man Alive: A True Story of Violence, Forgiveness and Becoming A Man was published in 2014, and he’s now working on his second book, Amateur.

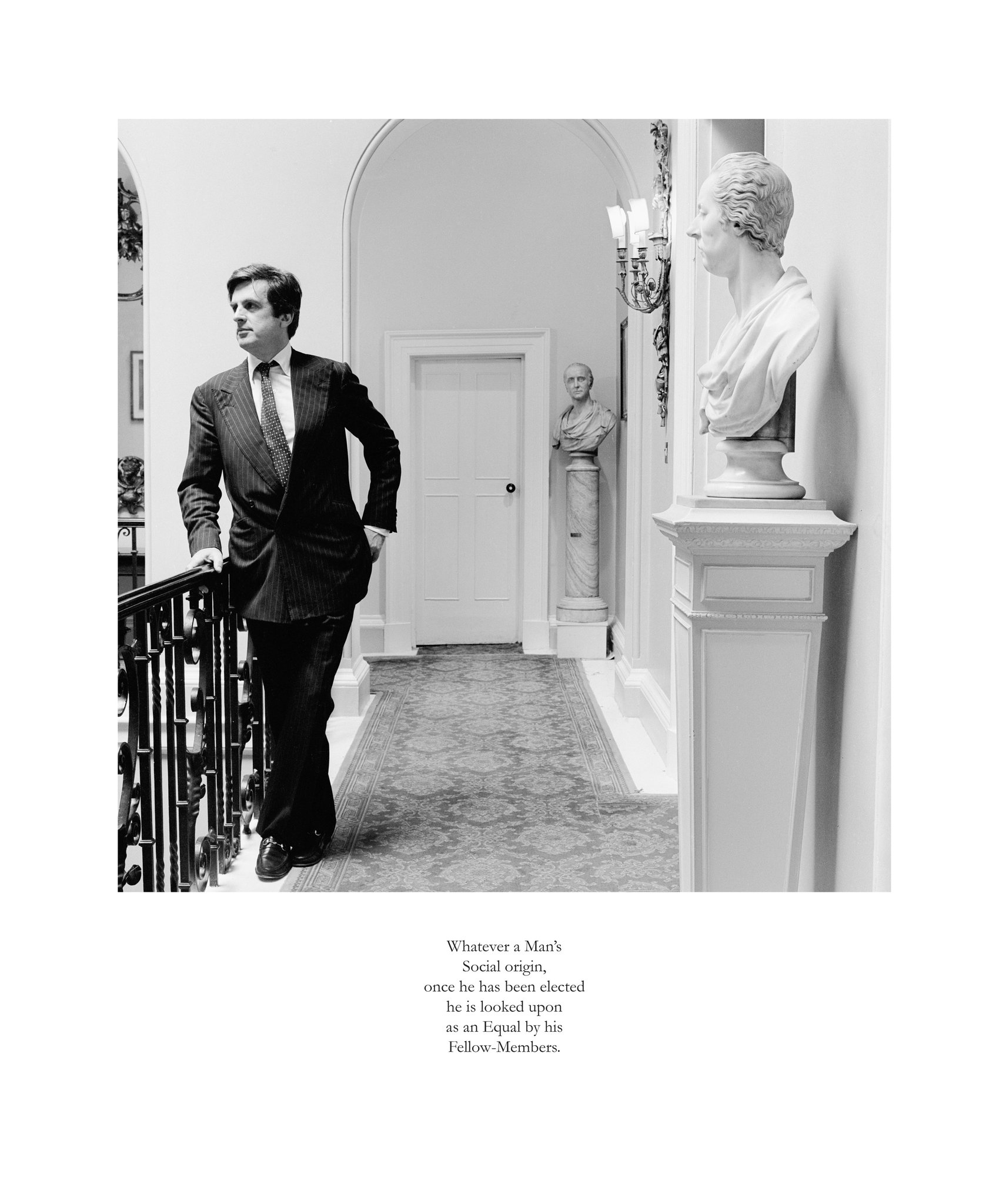

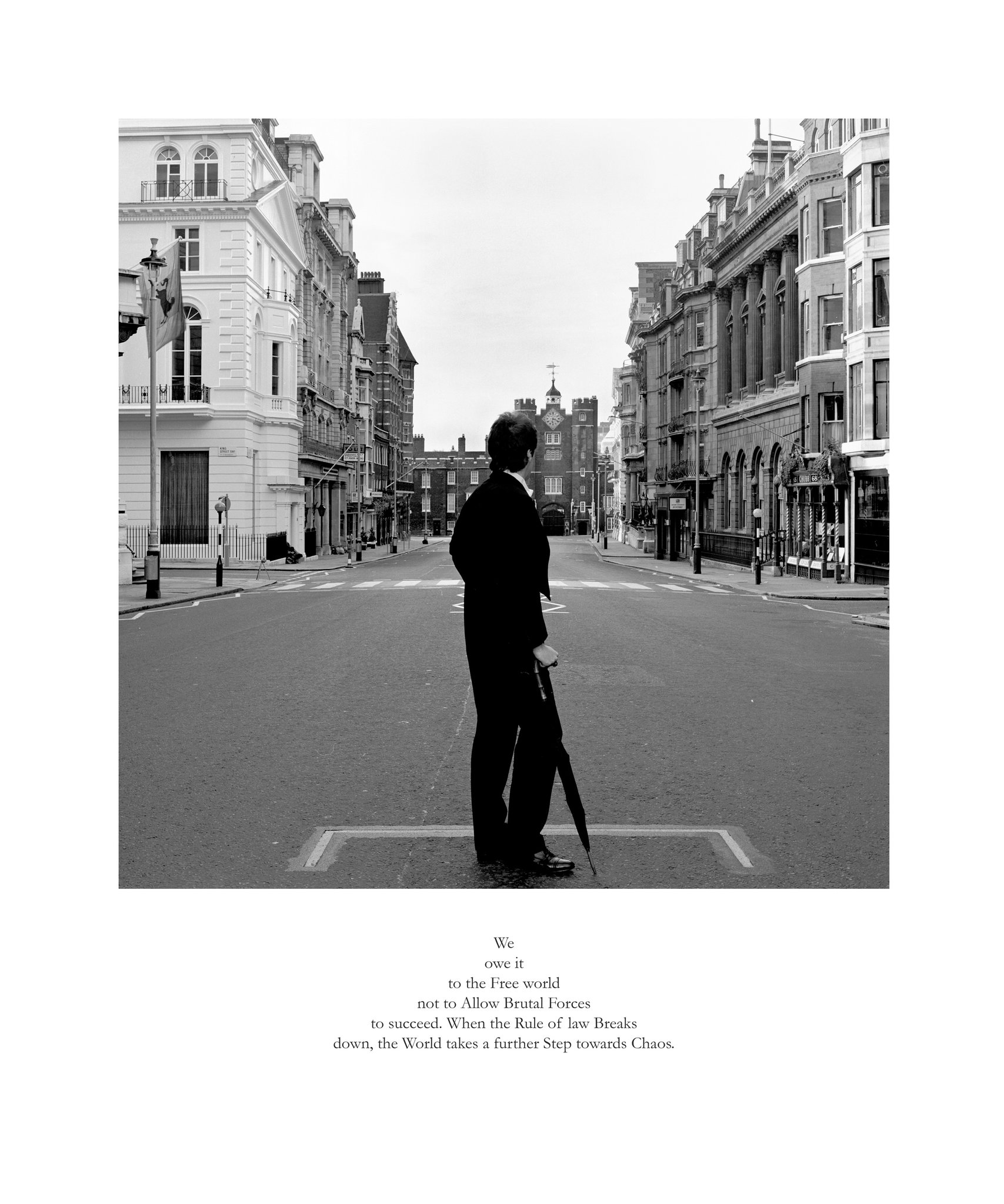

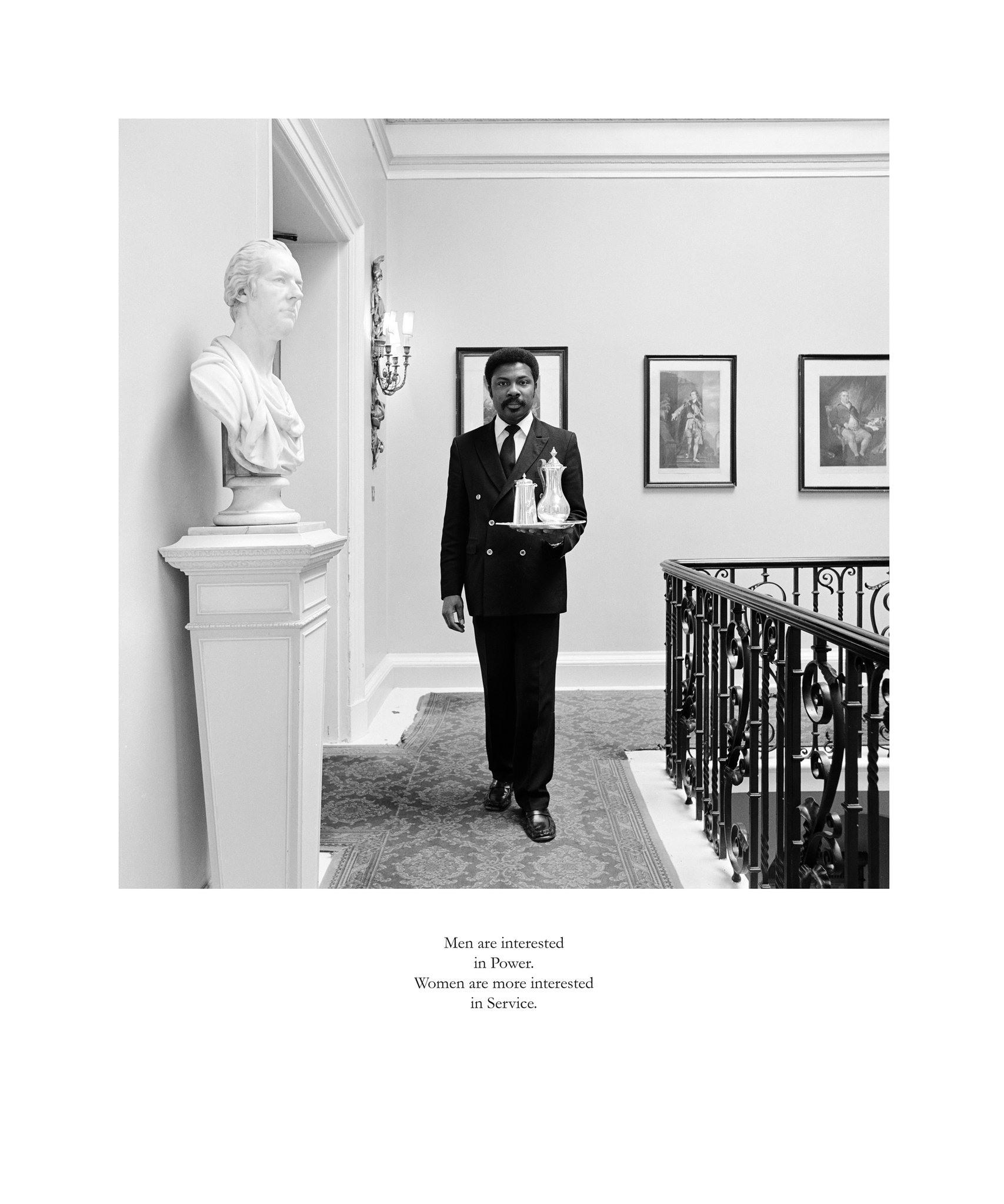

Karen Knorr is known for her architectural scenography, a style she codified in the 1980s: typically she creates fictionalised spaces to reflect on Western cultural traditions. In Gentlemen, a book published by Stanley/Barker in collaboration with Eric Franck Fine Art and from where these images are taken, she investigated the values of the London upper class by juxtaposing images of an exclusive 1980s gentlemen’s club with text from parliament speeches and news from the same era.

This article was originally published in Vestoj’s latest issue ‘On Masculinities,’ available on www.vestoj.com and in select bookstores now.