IT WAS CHRISTMAS EVE. Marya had long been snoring on the stove; all the paraffin in the little lamp had burnt out, but Fyodor Nilov still sat at work. He would long ago have flung aside his work and gone out into the street, but a customer from Kolokolny Lane, who had a fortnight before ordered some boots, had been in the previous day, had abused him roundly and had ordered him to finish the boots at once before the morning service.

‘It’s a convict’s life!’ Fyodor grumbled as he worked. ‘Some people have been asleep long ago, others are enjoying themselves, while you sit here like some Cain and sew for the devil knows whom. . . .’

To save himself from accidentally falling asleep, he kept taking a bottle from under the table and drinking out of it, and after every pull at it he twisted his head and said aloud:

‘What is the reason, kindly tell me, that customers enjoy themselves while I am forced to sit and work for them? Because they have money and I am a beggar?’

He hated all his customers, especially the one who lived in Kolokolny Lane. He was a gentleman of gloomy appearance, with long hair, a yellow face, blue spectacles and a husky voice. He had a German name which one could not pronounce. It was impossible to tell what was his calling and what he did. When, a fortnight before, Fyodor had gone to take his measure, he, the customer, was sitting on the floor pounding something in a mortar. Before Fyodor had time to say good-morning the contents of the mortar suddenly flared up and burned with a bright red flame; there was a stink of sulphur and burnt feathers, and the room was filled with a thick pink smoke, so that Fyodor sneezed five times; and as he returned home afterwards, he thought: ‘Anyone who feared God would not have anything to do with things like that.’

When there was nothing left in the bottle Fyodor put the boots on the table and sank into thought. He leaned his heavy head on his fist and began thinking of his poverty, of his hard life with no glimmer of light in it. Then he thought of the rich, of their big houses and their carriages, of their hundred-rouble notes. . . . How nice it would be if the houses of these rich men – the devil flay them! – were smashed, if their horses died, if their fur coats and sable caps got shabby! How splendid it would be if the rich, little by little, changed into beggars having nothing, and he, a poor shoemaker, were to become rich, and were to lord it over some other poor shoemaker on Christmas Eve.

Dreaming like this, Fyodor suddenly thought of his work, and opened his eyes.

‘Here’s a go,’ he thought, looking at the boots. ‘The job has been finished ever so long ago, and I go on sitting here. I must take the boots to the gentleman.’

He wrapped up the work in a red handkerchief, put on his things, and went out into the street. A fine hard snow was falling, pricking the face as though with needles. It was cold, slippery, dark, the gas-lamps burned dimly, and for some reason there was a smell of paraffin in the street, so that Fyodor coughed and cleared his throat. Rich men were driving to and fro on the road, and every rich man had a ham and a bottle of vodka in his hands. Rich young ladies peeped at Fyodor out of the carriages and sledges, put out their tongues and shouted, laughing:

‘Beggar! Beggar!’

Students, officers and merchants walked behind Fyodor, jeering at him and crying:

‘Drunkard! Drunkard! Infidel cobbler! Soul of a boot-leg! Beggar!’

All this was insulting, but Fyodor held his tongue and only spat in disgust. But when Kuzma Lebyodkin from Warsaw, a master-bootmaker, met him and said: ‘I’ve married a rich woman and I have men working under me, while you are a beggar and have nothing to eat,’ Fyodor could not refrain from running after him. He pursued him till he found himself in Kolokolny Lane. His customer lived in the fourth house from the corner on the very top floor. To reach him one had to go through a long, dark courtyard, and then to climb up a very high slippery stair-case which tottered under one’s feet. When Fyodor went in to him he was sitting on the floor pounding something in a mortar, just as he had been the fortnight before.

‘Your honour, I have brought your boots,’ said Fyodor sullenly.

The customer got up and began trying on the boots in silence. Desiring to help him, Fyodor went down on one knee and pulled off his old, boot, but at once jumped up and staggered towards the door in horror. The customer had not a foot, but a hoof like a horse’s.

‘Aha!’ thought Fyodor; ‘here’s a go!’

The first thing should have been to cross himself, then to leave everything and run downstairs; but he immediately reflected that he was meeting a devil for the first and probably the last time, and not to take advantage of his services would be foolish. He controlled himself and determined to try his luck. Clasping his hands behind him to avoid making the sign of the cross, he coughed respectfully and began:

‘They say that there is nothing on earth more evil and impure than the devil, but I am of the opinion, your honour, that the devil is highly educated. He has – excuse my saying it – hoofs and a tail behind, but he has more brains than many a student.’

‘I like you for what you say,’ said the devil, flattered. ‘Thank you, shoemaker! What do you want?’

And without loss of time the shoemaker began complaining of his lot. He began by saying that from his childhood up he had envied the rich. He had always resented it that all people did not live alike in big houses and drive with good horses. Why, he asked, was he poor? How was he worse than Kuzma Lebyodkin from Warsaw, who had his own house, and whose wife wore a hat? He had the same sort of nose, the same hands, feet, head and back, as the rich and so why was he forced to work when others were enjoying themselves? Why was he married to Marya and not to a lady smelling of scent? He had often seen beautiful young ladies in the houses of rich customers, but they either took no notice of him whatever, or else sometimes laughed and whispered to each other: ‘What a red nose that shoemaker has!’ It was true that Marya was a good, kind, hard-working woman, but she was not educated; her hand was heavy and hit hard, and if one had occasion to speak of politics or anything intellectual before her, she would put her spoke in and talk the most awful nonsense.

‘What do you want, then?’ his customer interrupted him.

‘I beg you, your honour Satan Ivanitch, to be graciously pleased to make me a rich man.’

‘Certainly. Only for that you must give me up your soul! Before the cocks crow, go and sign on this paper here that you give me up your soul.’

‘Your honour,’ said Fyodor politely, ‘when you ordered a pair of boots from me I did not ask for the money in advance. One has first to carry out the order and then ask for payment.’

‘Oh, very well!’ the customer assented.

A bright flame suddenly flared up in the mortar, a pink thick smoke came puffing out, and there was a smell of burnt feathers and sulphur. When the smoke had subsided, Fyodor rubbed his eyes and saw that he was no longer Fyodor, no longer a shoemaker, but quite a different man, wearing a waistcoat and a watch-chain, in a new pair of trousers, and that he was sitting in an armchair at a big table. Two foot men were handing him dishes, bowing low and saying:

‘Kindly eat, your honour, and may it do you good!’

What wealth! The footmen handed him a big piece of roast mutton and a dish of cucumbers, and then brought in a frying-pan a roast goose, and a little afterwards boiled pork with horse-radish cream. And how dignified, how genteel it all was! Fyodor ate, and before each dish drank a big glass of excellent vodka, like some general or some count. After the pork he was handed some boiled grain moistened with goose fat, then an omelette with bacon fat, then fried liver, and he went on eating and was delighted. What more? They served, too, a pie with onion and steamed turnip with kvass.

‘How is it the gentry don’t burst with such meals?’ he thought.

In conclusion they handed him a big pot of honey. After dinner the devil appeared in blue spectacles and asked with a low bow:

‘Are you satisfied with your dinner, Fyodor Pantelyeitch?’

But Fyodor could not answer one word, he was so stuffed after his dinner. The feeling of repletion was unpleasant, oppressive, and to distract his thoughts he looked at the boot on his left foot.

‘For a boot like that I used not to take less than seven and a half roubles. What shoemaker made it?’ he asked.

‘Kuzma Lebyodkin,’ answered the footman.

‘Send for him, the fool!’

Kuzma Lebyodkin from Warsaw soon made his appearance. He stopped in a respectful attitude at the door and asked:

‘What are your orders, your honour?’

‘Hold your tongue!’ cried Fyodor, and stamped his foot. ‘Don’t dare to argue; remember your place as a cobbler! Blockhead! You don’t know how to make boots! I’ll beat your ugly phiz to a jelly! Why have you come?’

‘For money.’

‘What money? Be off! Come on Saturday! Boy, give him a cuff!’

But he at once recalled what a life the customers used to lead him, too, and he felt heavy at heart, and to distract his attention he took a fat pocketbook out of his pocket and began counting his money. There was a great deal of money, but Fyodor wanted more still. The devil in the blue spectacles brought him another notebook fatter still, but he wanted even more; and the more he counted it, the more discontented he became.

In the evening the evil one brought him a full-bosomed lady in a red dress, and said that this was his new wife. He spent the whole evening kissing her and eating gingerbreads, and at night he went to bed on a soft, downy feather-bed, turned from side to side, and could not go to sleep. He felt uncanny.

‘We have a great deal of money,” he said to his wife; ‘we must look out or thieves will be breaking in. You had better go and look with a candle.’

He did not sleep all night, and kept getting up to see if his box was all right. In the morning he had to go to church to matins. In church the same honour is done to rich and poor alike. When Fyodor was poor he used to pray in church like this: ‘God, forgive me, a sinner!’ He said the same thing now though he had become rich. What difference was there? And after death Fyodor rich would not be buried in gold, not in diamonds, but in the same black earth as the poorest beggar. Fyodor would burn in the same fire as cobblers. Fyodor resented all this, and, too, he felt weighed down all over by his dinner, and instead of prayer he had all sorts of thoughts in his head about his box of money, about thieves, about his bartered, ruined soul.

He came out of church in a bad temper. To drive away his unpleasant thoughts as he had often done before, he struck up a song at the top of his voice. But as soon as he began a policeman ran up and said, with his fingers to the peak of his cap:

‘Your honour, gentlefolk must not sing in the street! You are not a shoemaker!’

Fyodor leaned his back against a fence and fell to thinking: what could he do to amuse himself?

‘Your honour,’ a porter shouted to him, ‘don’t lean against the fence, you will spoil your fur coat!’

Fyodor went into a shop and bought ‘himself the very best concertina, then went out into the street playing it. Everybody pointed at him and laughed.

‘And a gentleman, too,’ the cabmen jeered at him; ‘like some cobbler. . . .’

‘Is it the proper thing for gentlefolk to be disorderly in the street?’ a policeman said to him. ‘You had better go into a tavern!’

‘Your honour, give us a trifle, for Christ’s sake,’ the beggars wailed, surrounding Fyodor on all sides.

In earlier days when he was a shoemaker the beggars took no notice of him, now they wouldn’t let him pass.

And at home his new wife, the lady, was waiting for him, dressed in a green blouse and a red skirt. He meant to be attentive to her, and had just lifted his arm to give her a good clout on the back, but she said angrily:

‘Peasant! Ignorant lout! You don’t know how to behave with ladies! If you love me you will kiss my hand; I don’t allow you to beat me.’

‘This is a blasted existence!’ thought Fyodor. ‘People do lead a life! You mustn’t sing, you mustn’t play the concertina, you mustn’t have a lark with a lady. . . . Pfoo!’

He had no sooner sat down to tea with the lady when the evil spirit in the blue spectacles appeared and said:

‘Come, Fyodor Pantelyeitch, I have performed my part of the bargain. Now sign your paper and come along with me!’

And he dragged Fyodor to hell, straight to the furnace, and devils flew up from all directions and shouted:

‘Fool! Blockhead! Ass!’

There was a fearful smell of paraffin in hell, enough to suffocate one. And suddenly it all vanished. Fyodor opened his eyes and saw his table, the boots and the tin lamp. The lamp-glass was black, and from the faint light on the wick came clouds of stinking smoke as from a chimney. Near the table stood the customer in the blue spectacles, shouting angrily:

‘Fool! Blockhead! Ass! I’ll give you a lesson, you scoundrel! You took the order a fortnight ago and the boots aren’t ready yet! Do you suppose I want to come traipsing round here half a dozen times a day for my boots? You wretch! you brute!’

Fyodor shook his head and set to work on the boots. The customer went on swearing and threatening him for a long time. At last when he subsided, Fyodor asked sullenly:

‘And what is your occupation, sir?’

‘I make Bengal lights and fireworks. I am a pyrotechnician.’

They began ringing for matins. Fyodor gave the customer the boots, took the money for them, and went to church.

Carriages and sledges with bearskin rugs were dashing to and fro in the street; merchants, ladies, officers were walking along the pavement together with the humbler folk. . . . But Fyodor did not envy them nor repine at his lot. It seemed to him now that rich and poor were equally badly off. Some were able to drive in a carriage, and others to sing songs at the top of their voice and to play the concertina, but one and the same thing, the same grave, was awaiting all alike, and there was nothing in life for which one would give the devil even a tiny scrap of one’s soul.

Anton Chekhov originally published ‘The Shoemaker and the Devil’ on Christmas Day, 1888, in the Peterburgskaya gazeta newspaper.

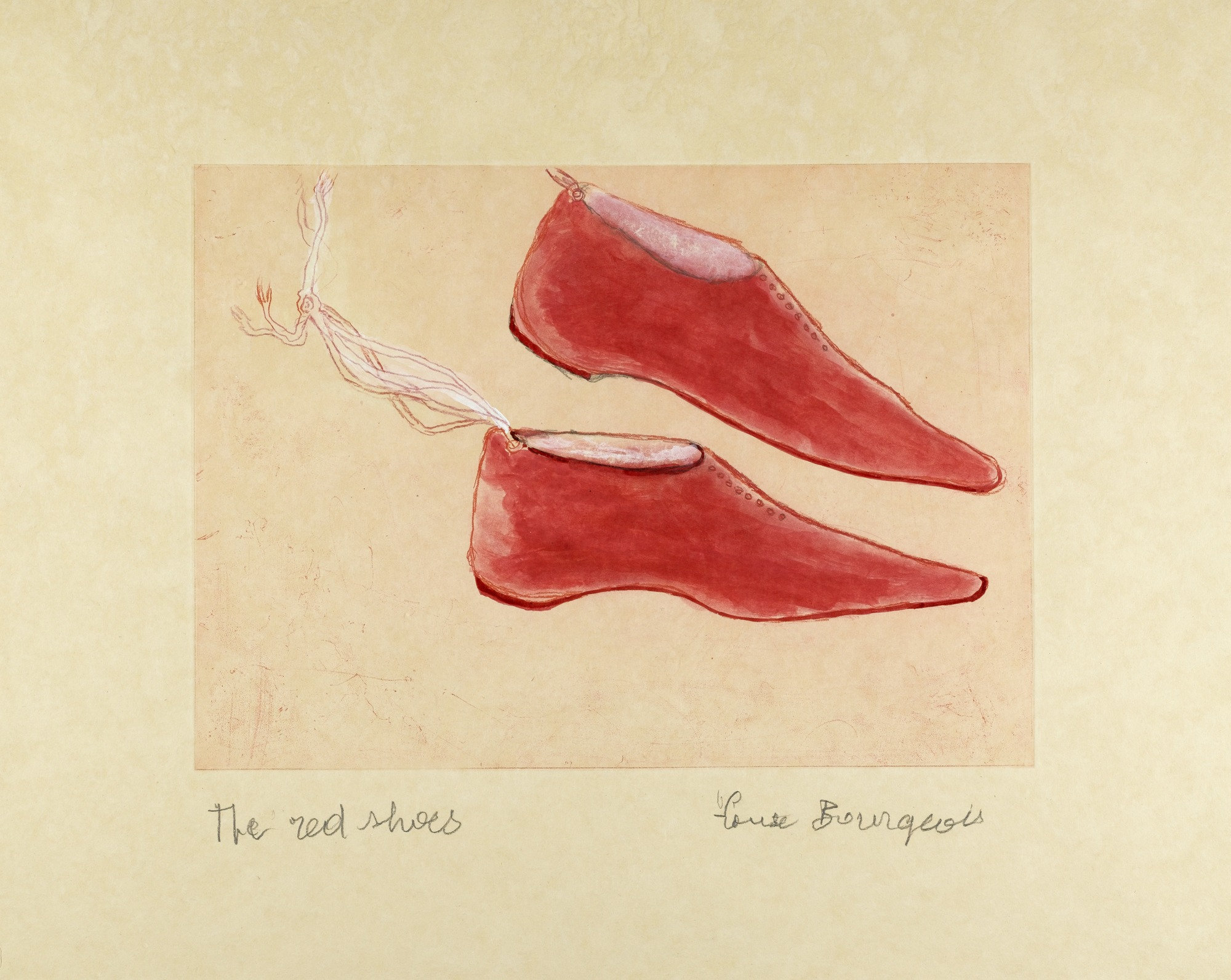

Image courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art (www.moma.org).