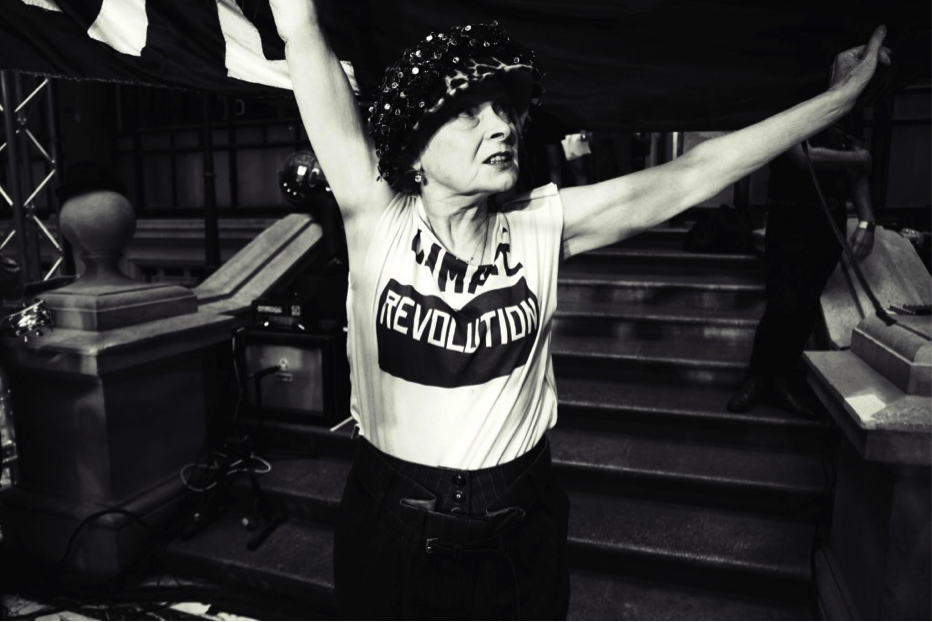

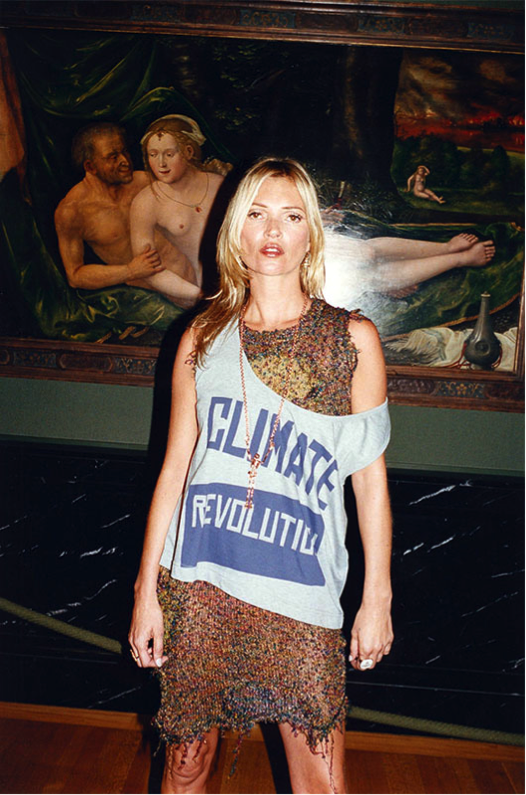

VIVIENNE WESTWOOD’S ABILITY TO provoke public discussion – both through her fashion and her media appearances – has characterised her career since the 1970s. In the past ten years Westwood has regularly taken advantage of her status to raise awareness on climate change and to protest against the political institutions that support the overexploitation of natural resources. As such, she is adamant that her clothes should be perceived as public statements and politically-charged products. The titles of Westwood’s latest collections mirror this; ‘Gaia The Only One,’ ‘Climate Revolution,’ ‘Save The Arctic’ and ‘Ecocide,’ all explicitly address environmental issues. It is no surprise then, that her autobiography is a further extension of the designer’s activist persona. But while the book explicitly presents her fashion and political engagement as parallel and complementary, it also downplays the contradictions at the roots of her public self. Specifically, it fails to resolve the ethical contradictions of the most outspoken activist against climate change in the fashion industry, who also happens to be the designer behind a global brand that produces seven different lines. In fact, the reader is often left wondering whether the designer’s apparently seamless navigation of celebrity culture, activism and branding makes Westwood’s persona a case of contemporary commodity activism rather than radical revolution.1

Published in 2014, Westwood’s self-titled autobiography is, more than most other examples of designer life writing, a case of celebrity autobiography. Westwood is not only an influential designer, but also the ‘godmother’ of punk, and a Dame that embodies a certain English eccentricity we have come to know and love. Name-dropping, quotes from famous musicians and actors, as well as personal letters to the likes of Naomi Campbell, are key ingredients of the book. Vivienne Westwood is also an example of collaborative autobiography; the volume was co-written with Ian Kelly, actor and biographer of fashionable figures such as Beau Brummel and Giacomo Casanova. Their collaboration is perhaps best articulated by Westwood herself in the book: ‘Nothing in the past is entirely true. But you are only in those scenes properly when they are put together. That’s what we should do, you and I, Ian: sew together all the life scenes.’ However suggestive, the sartorial metaphor is rather ill-suited. If the authorship of a garment is always collective, despite the symbolic identity between designer, maker and brand on the label, this is not the case in autobiography, where narrator and subject are usually the same person. Whether explicit or in the form of ghostwriting, then, collaborative autobiography is always bound to raise ethical concerns about the objectivity of the narrative.

Autobiography scholar G. Thomas Couser has indeed pointed out that ‘autobiographical collaborations are rather like marriages and other domestic partnerships’ in that writer and subject ‘produce an offspring that will derive traits from each of them.’2 Ian Kelly seems aware of the risks of collaborative autobiography. His attempts to distance himself from his subject and the fashion system at large are implicit in his narrative strategies. This is evident in his use of quotation marks to indicate direct speech from Westwood or members of her circle of family and friends as well as explicit clarifications. For instance, in one passage Westwood explains her love of platform shoes: ‘“[…] Women should be on pedestals. Like art. Sometimes. Or look like they have stepped out of a portrait. I wear them all the time.” (It’s true.)’ Through commentary like this, Kelly establishes himself as an external, objective narrator, trustworthy of honest, impartial portrayal of the designer. However, throughout the book, the extensive use of interviews establishes a format of oral history, text that – by definition – is subjective. Subjective anecdotes such as this are often the very stuff the mythology of fashion is made out of. A premise that makes the reader wonder what degree of truth is to be expected from an autobiography, one that has been called a ‘gossip session’ by the Press Association. Accusations of plagiarism and historical inaccuracy by Paul Gorman, author of the 2001 book The Look: Adventures In Rock and Pop Fashion, have also called into question the credibility of Kelly and Westwood’s account.3

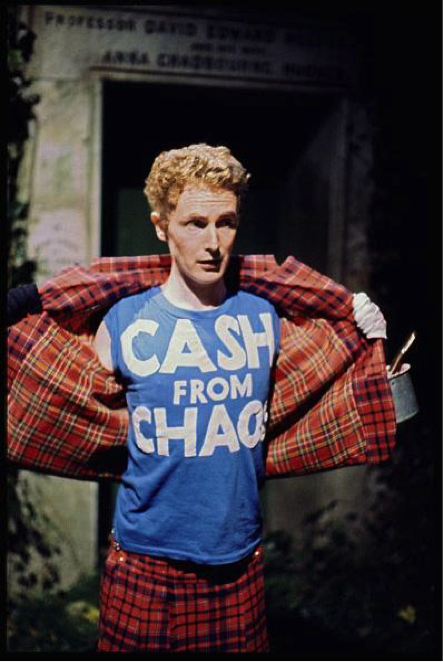

The narrative of Westwood’s autobiography is built on her parallel engagement in fashion and activism, a dynamic she has maintained since her punk years. She and her one-time partner, Malcolm McLaren have been credited with having made fashion explicitly political through the creation of the punk uniform. According to Westwood the pair were, at the time, heavily inspired by Guy Debord’s Situationist ideas, and supposedly originally conceived their clothing as ‘agitprop.’ In London during the Thatcher years, these political messages and motivations became the selling point with the disaffected youth market, de facto turning anarcho-Situationist ideas into a powerful marketing tool. Westwood acknowledges this in the book: ‘But I concluded very early on with punk that it was an immediate marketing opportunity […] punk is to do with an aesthetic but sometimes I think the only good thing that came out of it was the “Don’t trust the government” idea and that meanwhile I do think I looked great!’ Kelly also highlights this ‘shock and sell’ technique that McLaren and Westwood successfully championed – though, despite his claims of objectivity, he fails to point out the limited reach of the scene hosted in the different reincarnations of the shop on 430 King’s Road. In fact, the vast majority of ‘punks’ couldn’t afford clothes sold at SEX or Seditionaries (McLaren and Westwood’s infamous punk boutiques), nor were they influenced by the music of the McLaren-managed Sex Pistols. More often than not, punks would independently purchase commercial or second-hand fashion and alter it through DIY and a make-do-and-mend attitude.4 Ben Westwood’s claim that his mother and McLaren ‘were the beginners and enders of punk and that’s all you can say about punk’ – one of the many instances of oral history in the autobiography that is left unquestioned – sounds unrealistic to say the least and fails to recognise the essential cultural context of the movement in its entirety.

Westwood’s transition from punk to environmental activism is too readily resolved by the designer: ‘what I am doing now, it still is punk – it’s still about shouting about injustice and making people think, even if it’s uncomfortable.’ Yet what is more uncomfortable is, perhaps, her limited vision on sustainability in fashion, which borders on greenwashing and relies heavily on the rhetoric of spectacle – an ironic position considering the designer’s alleged familiarity with Situationism. While her donations to charity Cool Earth, occasional use of eco-friendly materials for her brand’s diffusion lines and advocacy across multiple platforms and events are worthy of recognition, her design house is nonetheless a multi-million global brand that neither makes its socio-environmental standards public nor provides any report or tangible data on its carbon footprint.5 Thus the seemingly easy transition from punk to environmentalism is more problematic that she lets on to be and, ultimately, highlights the uncomfortable blurring of political engagement and branding that has characterised her idiosyncratic career. In her autobiography, these ambiguities emerge at different moments through statements such as: ‘What I’m always trying to say is: buy less, choose well, make it last; though sometimes I might as well say, ‘buy Vivienne Westwood!’ While one may agree with a broad-sweeping mantra of ‘buy less, buy better,’ if we are to enjoy the privilege of choice, Westwood’s unabashed self-promotion ultimately undermines not only the authenticity of the persona she and Kelly present in her autobiography, but also her overall credibility as an activist.

Alessandro Esculapio is a writer and PhD student at the University of Brighton, UK.

See R. Mukherjee & S. Banet-Weiser (eds.) Commodity Activism: Cultural Resistance In Neoliberal Times, New York: NYU Press, 2012. ↩

G. T. Couser, ‘Making, Taking and Faking Lives: The Ethics of Collaborative Life Writing,’ Style, Summer 1998, 32, 2, p. 335. ↩

See http://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2015/sep/02/paul-gorman-vivienne-westwood-plagiarism-claim. ↩

See for instance S. Suterwalla, ‘From Punk to the Hijab: Women’s Embodied Dress As Performative Resistance, 1970s to the Present,’ in M. Partington & L. Sandino (eds.) Oral History In The Visual Arts, London & New York: Bloomsbury, 2013, pp. 161-169. ↩

See for instance http://eluxemagazine.com/magazine/vivienne-westwood-is-not-eco-friendly/. ↩