THE MUSEUM IS A site of power, both guardian and producer of cultural capital: museums define and reproduce notions of what is worthy of our gaze. The year 2017 reified fashion’s space within the museum: though debates as to its place in the museum still sputter on, another string of blockbuster shows in New York and London1 alone, confirmed that fashion, as a craft and art form, status symbol and performative practice, draws crowds and press in a way that few other creative mediums can do.

In the context of this increasing acceptance of the validity of fashion in museums, it is interesting to delve more deeply into what these blockbuster shows say about fashion, dress and clothes. How are clothes in the museum positioned and framed, and how do these ways of ‘dressing’ the museum shape collective ideas on our relationship to fashion and the creative self? Many of the successful 2017 exhibitions might be described as ‘designer-as-artist’ shows; shows which construct a visual narrative around the creative genius and modus operandi of a single named designer(s). These monographic exhibitions use the construct of the designer as the author (or auteur) to showcase the work of famous designers in relation to wider histories of fashion and dress, often (although not always) with secondary importance placed on the social implications of the clothing on display.

Two of the biggest fashion exhibitions of the last year, the elegant Balenciaga: Shaping Fashion at the V&A and the conceptual Rei Kawakubo/Comme des Garçons: Art of the In-Between at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, fit this model. As such viewers were treated to a reappraisal of Cristóbal Balenciaga’s technical innovation and design influence, through x-ray analysis that doubled as artistic intervention, a collaborative project with London College of Fashion students, and carefully chosen juxtapositions from the museum’s collection. The singular and spectacular innovation of Rei Kawakubo was celebrated and re-imagined, reconsidered within a conceptual framework of binaries and dualities (such as male/female, object/subject, clothes/not clothes and model/multiple) which were crossed and re-crossed as we walked around her voluptuous forms.

The monographic fashion exhibition builds upon an established exhibition-making tradition that fetishises and reifies the trope of the artist as lone genius, subtlety negating the broader creative networks and contexts in which ‘fashion’ is made. In positioning fashion as the output of a single creative mind these exhibitions often feed into the narrative so often presented by the fashion industry: where collections and brands derive from a single identifiable figurehead, rather than from collaborative studios and market decisions. Despite their extraordinary beauty and power, these exhibitions reinforce a very particular (and hierarchical) narrative of what fashion is; one, which privileges spectacle and craftsmanship over the meanings drawn from everyday dress. In presenting visual narratives that revolve around the designer-author and pristine showroom-ready garments these exhibitions present fashion as a meaningful yet glossily impenetrable surface, glamour as the implicit desired end result of our self-fashioning. As social theorist Nigel Thrift2 writing on the allure of consumer goods suggests, glamour is produced through the construction of smooth and shiny surfaces, a coalescence of technological advancement and capitalist disavowal of the untidiness of the everyday. Often this focus on fashion as a beautiful spectacle comes with the exclusion of embodied and social approaches to both fashion and dress, an exclusion that reinforces hierarchies of cultural production, leaving high fashion within the reach of a minority.

Our relationship with clothing is not only aspirational and image led, a myth that spectacular exhibitions cannot help but propagate: it is cultural, sensory and embodied, and we, as everyday dressers, are also authors of fashion. However too often fashion exhibitions centre around visual engagement with the glamorous surfaces of fashion, rather than forge connections to the real world of senses and emotions. Does this emphasis on a particular kind of visual encounter limit the viewer’s capacity to engage with the garment as a locus of multi-sensory experience, the ways we feel in and feel about our clothes?

The monographic imagining of fashion in museums sits in contrast to fashion as bodily and lived; the everyday experience of wearing clothes. We produce our clothed identities through acquiring, styling and collating clothes from multiple sources. These ideas resonate in viewing an inconspicuous closet moved from its original home in a small Greenwich Village apartment to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where it comprised the entirety of the exhibition Sara Berman’s Closet on view last year. Inconspicuous yes, but enormously powerful as we related the neat piles of clothing and other personal possessions such as worn shoes, a wooden recipe box and a perfume flask, to the tastes, smells and movements of everyday life. With the knowledge of the subject’s various pasts gleaned briefly through a wall text, we understood that for Berman, dress was a process of self and re-fashioning, the confluence of multiple agents and selves. We wondered, did her dutifully ironed and folded clothing wipe away the clutter of a failed marriage, or hark back to her childhood home in Tel Aviv, for example?

The exhibition didn’t answer these questions, but it provided the impetus for us to redirect the line of questioning. How do we fashion ourselves in our own daily practice of dressing, through acts of mimicry, appropriation and subversion, for instance? Occasionally in the fashion exhibition the imperfect and changeable nature of our relationships to clothing are brought to the fore – the scuffed heels and taped hems of Isabella Blow (written about so beautifully by fashion theorist Caroline Evans) displayed in Isabella Blow: Fashion Galore! (2013-14, Somerset House) for example; which poignantly embodied a fashionable life lived. These poignant garments are an example of what museum scholar Jeffrey David Feldman3 describes as ‘contact points,’ objects, which through bodily contact have become a link or bridge between the viewer and the display. As traces of their encounters with bodies other than our own, these accruals of information are the links that allow a meaningful encounter to occur. Whereas, according to Feldman, in locating the museum encounter as primarily visual, we often disregard the haptic contexts of their previous uses, and the ‘rich sensory information accumulated in objects.’4 This information, the material ways that a garment changes through interaction with the bodies and things which surround them, are powerful reminders of our own subjective experiences and emotions. In failing to highlight these contact points do fashion curators miss opportunities for their public to make these connections?

In these contexts, how might clothing on display embody the social person who once wore them? A reframing of fashion authorship in exhibitions may be a means to spur broader definitions of dress to better reflect our lived experience. Several recent exhibitions challenged the primacy of the designer-led fashion exhibition by positioning the wearer as ‘author’; as the primary creative agent of fashion practice. In this reframing they shift the creative focus from designing dress to the collation of a wardrobe, its styling. Sitting between biographical overviews, artist’s retrospectives and social histories, two recent exhibitions exploring twentieth-century artists’ lives and identities, Gluck: Art and Identity at Brighton Museum and Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern at the Brooklyn Museum both reveal a conflation of the creative, professional and personal self through dress. Fluidly moving between the author-artists’ creative outputs and dressed identities, both these practises were presented as a means of maintaining creative personae. In these explorations of the wardrobes of a famous artist protagonist, whose creativity is already acknowledged, the garments may be everyday, but the wearer extraordinary. When the ‘wearer’ is an artist or designer, their creative capacity, and thus the validity of dressing as an aspect of their creative output, is harder to challenge and fits neatly within accept narratives of authorship within artistic production.

Beyond the designer-led fashion exhibition we see the intersections between style, biography social and personal histories more frequently. Clothing took a lead role in exploring how O’Keeffe constructed her public image, a central premise of Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern. Displays of O’Keeffe’s sewing tools alongside homemade garments allowed us to begin to grasp the embodied context of production, while photographs and texts describing her everyday life began to shape the absent social body. Conversely, we left Sara Berman’s Closet wanting to know more about the subject behind the display. The exhibition presented the psychical taxonomising and curating of a wardrobe by a relatively unknown person, as a creative act. Viewers connected to the ‘everydayness’ of the scene, simple folded garments and other personal objects in a closet, while reflecting on how their own clothing choice and organisation might also function as creative acts. By leaning on personal histories and the familiarity of the everyday, these two shows provided tools to enable visitors to apply their experiences as wearer-authors themselves. To acknowledge creative agency located not in acts of design but in the production of identity through the ready made.

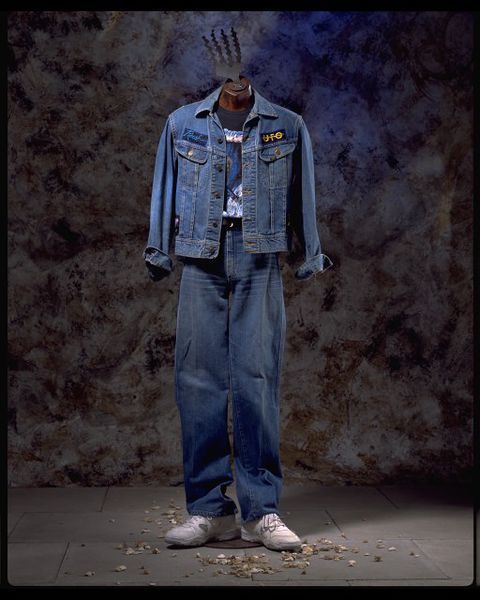

In parallel, a spate of thematic shows displaying clothing belonging to anonymous wearers or made by anonymous hands brings a very different perspective on dress. In Items: Is Fashion Modern? at the Museum of Modern Art, display objects functioned variously as archetypes, stereotypes and prototypes of a design idea, encouraging viewers to consider the creative practises of both the high fashion designer and mass-manufacturer. The equalising display of a range of objects challenged hierarchies of visual culture. The wearer-author entered into the exhibition narrative through the display of garments that were ‘everyday,’ such as a red Champion sweatshirt and Levis jeans. Despite their unworn nature, these garments contain elements of Feldman’s ‘contact points,’ for in viewing them, our bodies ‘fit’ back to them through memories we possess of wearing similar garments. Although Items unpacked traditional boundaries between high and low design, it lacked tangible engagement with the experiential and bodily elements of dress, which blocks us from identifying as author of these narratives.

In contrast, bodies were materialised and made playfully present in North: Fashioning Identity at Somerset House. Despite a limited amount of clothing on display, fashion was the central focus in North, an exploration of the image and culture of the north of England. Multilayered installations shaped a picture of looking and feeling ‘northern’: garments featuring alongside diverse groupings of multimedia work, photography and film. Jeremy Deller’s interactive interiors asked viewers to sit in others’ chairs, and to contort their bodies to another’s posture, a demand which spoke to the fact that our dress is an interface between the body and space. Installations by designers John Alexander Skelton and Christopher Shannon, and Jason Evans’ photographs, showed clothing in contexts of a constantly refashioning self, which exposed a subtext of self-authorship and the embodied nature of dress.

The ways clothing is mediated to a museum audience affects collective ideas on the significance of clothing and dressing, and in turn has the potential to shape people’s realities and agency. The anxiety expressed about fashion exhibitions in museums can often be understood as a fear that, in bringing clothes into the gallery it will become a site of commerce rather than culture; a glorified designer showroom. In order to differentiate the role of cultural institutions from spaces of commerce and fashion media let us look for ways of integrating the embodied and experiential nature of our everyday relationships with clothes into the fashion exhibition. Whilst it is undoubtedly true that the increasing collaboration between big brands and big museums both alter and reinforce hierarchies of cultural capital, exclusivity and wealth, might dress in the museum also offer an opportunity to democratise and enliven these sites of power, so that they become spaces for radical affect.

Ellen Sampson and Alexis Romano are co-founders of the Fashion Research Network (London). Dr. Sampson is an artist, curator and material culture researcher, and Associate Lecturer at Chelsea College of Art. Dr. Romano, a historian of design and visual culture, is a Visiting Lecturer at Parsons, the New School for Design.

A sampling of these shows include Paris Refashioned, 1957-1968; Black Fashion Designers; The World of Anna Sui; Veiled Meanings: Fashioning Jewish Dress; Present Imperfect: Disorderly Apparel Reconfigured; fashion after Fashion; Counter Couture: Handmade Fashion in an American Counterculture; Jessica Ogden: Still; and Volez, Voguez, Voyagez – Louis Vuitton. ↩

N Thrift, ‘The Material Practices of Glamour.’ Journal of Cultural Economy, 2008. ↩

JD Feldman, ‘Contact Points: Museums and the Lost Body Problem,’ in E Edwards et al, ed., Sensible Objects: Colonialism, Museums and Material Culture (Bloomsbury). ↩

Ibid., 251. ↩