IT’S 9PM ON A Sunday evening in April. Hundreds, maybe over a thousand, spectators dressed in gold and white are crowded around a makeshift stage the length and breadth of an Olympic swimming pool. There are babies and toddlers, teenagers and parents, grandparents, great-grandparents and a thirty-five-piece brass orchestra crammed beneath a decorative but not entirely protective bamboo shelter outside the Pura Sakenan temple in Petulu, Bali. When it rains, it drenches but no one moves; rather, revellers huddle close, sometimes eight to an umbrella as sanctification for the sacred Barong dance begins.

First, a prelude by the instrumentalists: the gamelan gong. Spearheaded by the whimsical suling or bamboo flute and carried by the rapid puncture of the metallophone, I hear light and fire as musicologist Colin Mcphee calls its alternating rhythms.1 Next, five women dressed in white carry platters of artfully arranged fruit to centre stage. They lay mats of palm on a red-carpet stage and place the offerings before them. One woman bends to splash holy water over the picnic. With striking posture, she rises and walks around the edge of the carpet, blessing the audience with her tonic as she goes. Enter: resplendent male warriors known as baris enter carrying sharp, pointed spears. They wear embroidered gold and red shields over loose white garb and sit at intervals holding the space. Finally, the costumes parade by. They are not worn but carried above the head by aides in bit parts: the crazed but joyful painted masks of three Barong separated from their shaggy bodies and the grey-haired witch, Rangda, hoisted high on a stick. More special water is spritzed about; a swath of incense is lit, and a high priest sits at the nexus of it all, praying.

Now, the dance may commence, and on this night, it lasts six hours.

The Barong narrative or Calon Narang as it is also called, is simple but it is serious practise for believers: Balinese Hindus and Indigenous tribes alike. The Barong is a protective force. Imported from Chinese mythology a millennia ago, he is known as the ‘king of the spirits’ and takes the form of an animal – most often a lion, but also a dog, pig, elephant or tiger – when he is animated in gesture and costume (he also sits as a sort of stone figurehead at the entrance to traditional buildings and temples). The witch Rangda is his opposite. She is the yin to his yang, evil twin to his overwhelming goodness and scandalmonger of disease and destruction. If there a number of cancer diagnoses in a single village say, it is considered corollary of Rangda’s demonic, black magic and while she wants to wreak havoc, the Barong are empowered to safeguard against it. The dance, which is a really a clash, goes on and on.

At one point, a legion of young male kris dancers coveting long sharp knives come to the Barong’s rescue. They howl and chortle while holding the knives to Rangda’s haggard masked-face, but her strength is over-powering and they turn the knives on themselves (the penetration of skin is shallow, but rumour has it a weak dancer may injure or kill himself under her spell; of course this ups the ante). There is more cavorting between the two central forces and the battle ends with capitulation not victory. Rangda is pacified by the opportunity to express herself and the Barong’s emancipating qualities are strengthened. The ritual is prophetic and cathartic; a physical manifestation of the human struggle for virtue or dharma that never ends.

‘Every community should have a Barong for security,’ Made Abri, a wiry-looking professional dancer with the Sekhe Gong Pancha Artha Company and the character of Rangda tells me on this night.2 ‘My community does not pray to another.’ Indonesia’s religious orientation is predominantly Muslim but the petite island of Bali is principally Hindu and outside the capital, Denpasar, it’s coagulation of small, Orthodox villages each house three temples. The Pura Puseh is where the God Brahma allegedly resides; the Pura Desa is where Vishnu lives and Shiva’s Pura Dalem or ‘the death temple’ is where cremations take place. When the costumes are not in use, they are stored on a plinth, facing west in the Pura Dalem and locals may come to pray at liberty. If a villager falls ill, the priest usually dips the beard of the Barong into holy water and dabs it on the ailed as a form of spiritual sanitisation. If the illness is endemic, he calls a Barong dance.

‘In my childhood village, Banjar Tebesaya, we have Barong dance very often because many disease happens,’ Ni Wayan Yudiani, Abri’s wife adds. ‘Disease we call hunk. It is whatever pain leads to death.’3

Dance in Bali is considered holy practise. There are dances for the Gods known as wali and dances for tourists or bule referred to as Bali Balihan and the Barong is performed in both capacities but with different intents. Somewhere in between are semi-sacred dances, or narrative aphorisms of the religion called bebali. They are intended for locals as educational entertainment but not for bule. If a bule would like to watch a wali or bebali enactment, they may attempt loitering at the skirts of a ceremony – easy to find thanks to the metallic pitter patter of the gamelan gong, but hard to penetrate – or request an invitation from a Balinese family and approval from the village priest. Naturally, they must also don traditional dress: double-layered sarong, shirt and headscarf for men and tightly-bound sarong, lace blouse and sash for women or they risk arrest. These are lawful distinctions after all. Designed to keep the devotional as beautiful as it may be to holiday eyes, free from mere spectacle.

Most bule as you might imagine then, tend to settle for Bali Balihan depictions of the Barong and other dance forms, and this is the way it’s designed to be. Tourists get a glimpse of the god-inspired glitz that Balinese dance can be and the support the economy, while locals are not thrust into explaining or diluting their rituals for the benefit of the uninitiated. The presentations are similar, but not the same. The Bali Balihan performances may appear religious because they are appropriated from wali storylines, but they are not consecrated and therefore considered dead, according to French anthropologist Michel Picard.4 The wali enactments can come across as amateurish from a western perspective – one that prizes technique, impact and narrative over intuitive meandering – and yet they are said to be alive,5 because the temple settings, costumes and dances are designed to invoke the supernatural called sakti. In the former, dancers perform an offering for tourists; in the latter, they sublimate themselves for those notorious connoisseurs called Gods.6 ‘We can say that all Balinese dances are religious in nature because even those that are secular have something to do with the religious life of Balinese society’ writes the Balinese cultural critic, I Gede Arya Sugiartha.7 It’s just that some are more religious than others.

Abri discerns between the two forms: wali celebrations are a way to clean away bad spirits he tells me, whereas dancing for tourists is practise. ‘It is very difficult to dance the character of Rangda,’ he says. ‘If not practise, can’t dance.’8 Rangda, who is always played by a man, wears long-matted hair and large tusks. Her nails curl seven-inches-long and she carries a rag ostensibly infused with black magic. In contrast to the fluid movements of traditional Balinese dance, she tends to stand rustically with legs apart and hands trembling. When the kris dancers attack, she is almost blasé. The Barong in contrast, is danced by two men wearing jester’s pants and bells on their ankles. In a routine that is playful, even childlike in its jumbly form, they perform leaps and turns in perfect synchronicity while energising a bear-like façade that is roughly two metres long and weighs at least fourteen kilos. ‘It’s hard for my head. Very heavy,’ says Abri of the character he prefers not to play. That the Bali Balihan shows pay cash and the religious revelries do not, does not seem sway Abri’s focus. It’s the connoisseurs he cares to impress.

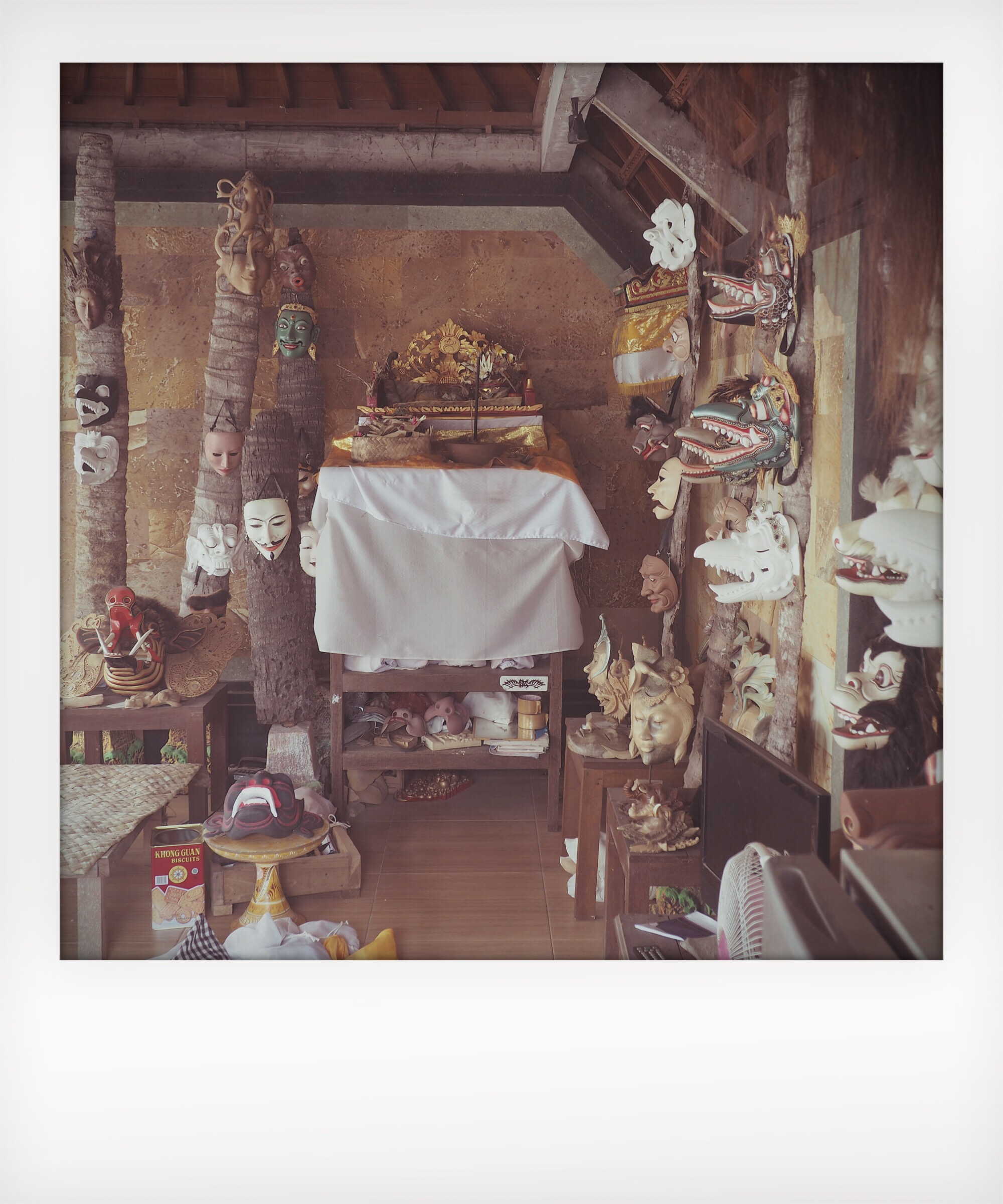

Nyoman Setiwan, a broad-shouldered costumier offers more context when I visit his studio in Sukawati. ‘In Bali, it’s more important to have a good connection with God than money in the bank. If you have a lot of good karma it can help you,’ he says.9 Setiwan is a fourth-generation mask-maker and one of only three artisans on the island relied upon to carve and appendage sacred masks: Barong and Rangda, but also Topeng façades for Bebali rituals. More than half his business is ‘sacral’ as he puts it, which means the manufacturing process is different but also, he doesn’t charge for his time or expertise – even when materials surmount to over US $15,000.00 as they do for a Barong when I visit (nestled into his studio altar, Setiwan shows me the donation he received for the job: roughly US $350.00).

‘For example, my daughter is blind,’ Setiwan tells me as he paints a decorative mask of Visnu for an American theatre producer. ‘When I go to the specialist doctor, I must have a lot of money.’ He doesn’t have a lot of money he says, so he applied for assistance through Rotary Australia, a health-based charity with international reach and as karma would have it, his application was granted. Since then, she has undergone three operations at the Princess Margaret Children’s Hospital in Perth and she sees with low vision. ‘This is why I make the sacral masks,’ Setiwan tells me. ‘The reality is god helps me with no money.’

To look at two Barong costumes – one fashioned for tourists and the other for religious purposes, it can be difficult to see the disparities. Aesthetically, the variances are subtle: a wali barong sports hair glossy like a shampoo advertisement – sometimes it’s human hair; sometimes horse, goat or the stringy park of the prakso tree – and a Bali Balihan does not. It looks synthetic. The painted features of a wali mask appear softer, almost milky, an upshot of using ground, stone pigment instead of acrylic paint. The Bali Balihan version is more defined. And then there is the gilt crown. If the village commissioning the ceremonial costume is wealthy, a tourist destination perhaps, the tiara will made of layers of gold leaf while the commercial emulation is cut from leather and spray-painted. The similarities are refined.

Spiritually however, the distinctions are profound. They are niskala, unseen: a product of fabrication techniques and numerous rituals believed to imbue the ceremonial costumes with spiritual energy that improves the quality of dance. ‘Taksu is very important in the wali dance,’ explains I Wayan Suweca, a music and dance professor at the Indonesian University of Arts. Taksu, which roughly translate as charisma or showmanship, is matching technique with spiritual power he says. To create it, dancers must be well trained in the minutae of the form – the Barong dance is markedly different from the regal Legong for example – and know how to ‘channel,’ which is aligning themselves with spirit they intend to portray. ‘I ask my students: what is the god of Barong? How do we learn the magic power of the Barong?’10 The central skill he says is prayer. ‘In Bali, dancers always pray before they perform.’ Usually they pray at their family temple before arriving, with fellow dancers before the show and with the audience on stage – wali or not. If they are dancing wali, they will also take holy water, offer flowers, fruit and submit to the almighty again before they dress. ‘Before we put the costume on, we ask for the character’s spirit to come into the body,’ Suweca tells me. When the costume is fitted, it acts as a kind of catchment for the spirit’s intent, and on a good day the dancer will slip into trance. This is a sign they are at one. Good practise if you will.

‘Sometimes, trance but not always,’ Abri says simply of wearing the sanctified garb.11

To begin the process of making divinely charged dress, Setiwan always starts on what he calls a special day. ‘I normally start in Saraswati and finish again in Saraswati. This is normal, but some people come in full moon and finish in full moon.’ Saraswati day is every six months on the Balinese calender (Balinese months are thirty-five days). It’s auspicious and a day when more handmade gifts than usual are extended to the goddess of knowledge and arts, Saraswati. The full moon is also providential, and it’s by the midnight light, Setiwan offers a woven basket of goodies – hydrangeas and marigolds, bananas and mangosteen, an egg ‘symbolising life’ and rice crispies – to the almighty and pule tree he intends to cut from. ‘I say to the tree, ‘It’s Nyoman, I want carving for the mask. Please give me some good spirit for the wood. I want good taksu.’ Then he makes a modest incision in the tree which is grown in temple or cemetery grounds and cuts enough wood to make the mask. ‘I say thank you.’

Afterwards, with log and basket full of blessings, he heads home where he places the hamper beneath a small shrine in his open-air workshop; and there it stays emanating positive vibes until the visage is finished. This usually takes six months to a year depending on the job and his energy levels (he only works when he feels buoyant). At which point, he performs a cleaning ceremony called prasita, and sends the costumes back to the commissioning temple for more rites. These are known as pasupati. One is with a high priest and the other is a performance at midnight within graveyard walls. ‘With prasita, the power may be 40%. If after pasupati, all the gods and spirits give the power, then power is 100%,’ Setiwan assures me.

The offerings and acts of reverence, special modes of assemblage, prayer and dance all work to imbue the costumes with magical properties. This vitality I am led to believe helps bring the dancers into character and matched by skill denotes superb delivery. We have taksu. The more the dancers perform, the better the spiritual oomph of their garb and provided the dancers are well-trained – which they often are given the omnipotence of dance training; students at public schools start learning at the age of six – the show comes off. Gods are entertained. Locals are too, as submission and spectacle morph into a culturally affirming product galvanising community; tourists get a peek through its evolution. As the writer Edward Herbst notes, ‘In Bali, beauty within ritual is a basic ingredient of efficacy, and in a sense, any social activity at all.’12 Lucky are those privy to the culture.

Gudrun Willcocks is a writer who holds an MSc in Journalism from Columbia University, New York City. She lives in Sydney and specialises in writing about dance.

Colin Mcphee, Music in Bali, Yale University Press, 1966. ↩

Interview with the author, April 28, 2019. ↩

Interview with the author, April 28, 2019. ↩

Michel Picard, Bali: Cultural Tourism and Touristic Culture, Archipelago Press, 1996. p.160 ↩

Ibid. ↩

Edward Herbst, Voices in Bali: Energies and Perceptions in Vocal Music and Dance Theatre, Wesleyan Press, 1997, p.122. ↩

I Gede Arya Sugiartha, Balinese Dance and Music in Relation to Hinduism, SEAMAO, 2018, p.17. ↩

Interview with the author, April 29, 2019. ↩

Interview with the author, May 8, 2019. ↩

Interview with the author, June 11, 2019. ↩

Interview with the author, April 29, 2019. ↩

Edward Herbs, Voices in Bali: Energies and Perceptions in Vocal Music and Dance Theatre, Archipelago Press, p.122. ↩