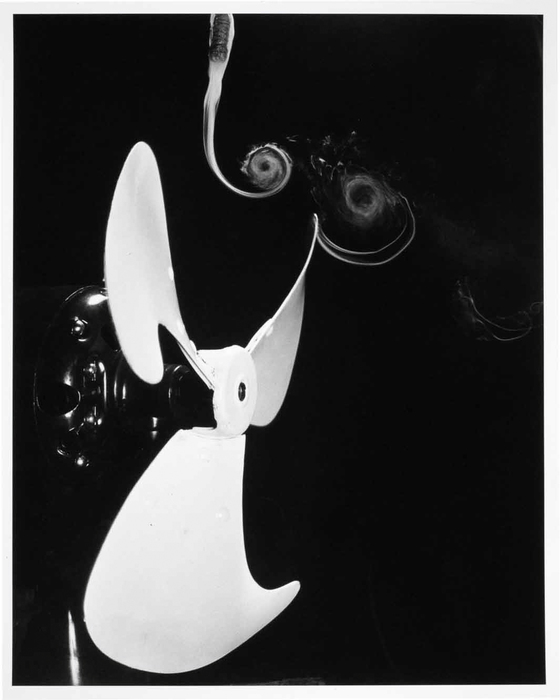

Fan and Smoke, 1934. Courtesy ICP.

Leather in all its variations becomes the smell of my father’s presence. A worn pouch in which sweet pipe tobacco was stored, the generations-old razor strop that hung in the bathroom. Shoes polished every week with a rag swirled in a gelatinous block of mink oil, a brown leather bomber jacket from the late 50s, its heavy folds frozen in place with muscle memory. And myriad colognes, the last ritual of grooming. According to society, scent should have been introduced through my mother and her perfumes, one of the first lessons of the Western feminine path of desire and its becoming. But as Wayne Koestenbaum writes, ‘as if we could neatly divide male and female dreaming!’1

A lipstick, an eyelash curler, a fine-brushed liquid eyeliner. My mother’s minimal process, the application of each as careful and studied as the stroke of her calligraphy brushes. The abbreviated beauty of motion echoing the gendered learnings of a specific culture. There was an absence of scent which I craved, associating it with a wild luxuriance I knew from playing in a rampant garden and images of classic movies, where every woman had a cache overflowing with perfume. The great black and gold stoppered boules of Lanvin—Arpège or My Sin on Bette Davis’s vanity in All About Eve, the towering factice of Robert Piguet Bandit in the Paris bathroom from which Ann-Margret applies in delight in Made in Paris spoke to some secret world. Perfumes became the ultimate luxury in my eyes, and the ultimate femininity. My assumption was that this near-mystical sillage, like the distraction of a magician’s smoke, would transport me to womanhood. But I learned a scented path is as complex in its revealings of desire and development as any perfume’s structure.

In place of a vanity, a cupboard, unassuming with white wooden shelves. In it, masculine became feminine, then neither and both. Unspoken permission, joyful olfactory explorations where everything became possible. So much of perfumery is olfactory sleight of hand, and a leather scent is never simply leather, but contains anything from birch tar or galbanum or violets, fruit to opoponax. The liquid within almost any perfume bottle is a chameleon, altering with the different skins it encounters, an ongoing Ovidian transformation from antiquity to the present. Perfume means ‘through smoke,’ and we emerge from bottles changed. I cannot remember the first commercial scent of my father’s that I surreptitiously tried—for he also made his own simple colognes—Puig Quorum, Lagerfeld Classic, Knize Ten, or Pierre Cardin, but what I immediately knew without a more articulate means of expression was our skins reflected both shared and different facets. These could not be dismissed as merely masculine or feminine, which turned my thus-far understanding of perfumes and relation to them upside-down. Writing about the artist Sherrie Levine, Donald Barthelme notes, ‘A picture on top of a picture. What happens in the space between the two.’2 Somewhere between masculine and feminine lies the understanding of all desire.

In the early 80s, femininity was big and colourful. The women of the magazines I adored wore clouds of Bellville Sassoon and the electric colours of Yves Saint Laurent; too much was never enough. Perfumes reflected these. The ‘big’ 80s scent is now a cliché, due in part to releases as Giorgio Beverly Hills, Dior Poison, and Calvin Klein Obsession, extending to teenage scents such as Coty Exclamation. Though men’s scents had their own notoriety—Guy Laroche Drakkar Noir and Yves Saint Laurent Kouros being permanent ghosts of high school hallways well into the 90s and beyond—I found the bottles which lined my father’s shelves subdued in comparison. Without the technical vocabulary of perfume, I knew them as what I already knew of the world: the scents of walking outdoors and gardens, antique shops, closets, and the small collection of objects my parents had acquired together. Despite the abundance of bottles which did not speak to wealth but the necessity of frugality which determined our lives, my father would scour outlet stores for discounted bargains, and there was an unconscious curation in his small collection which reflected his quiet nature. To wear or be worn is a choice, and in scent I discovered sillage as an extension of myself.

Calvin Klein’s CK One was yet to be imagined, and Yves Saint Laurent’s 70s utopian dream of a shared perfume, Eau Libre, had failed. Perfume was firmly entrenched in gender, each side striving to be the ultimate embodiment of femininity or masculinity. Yet for some reason a lot of what my father wore—fougeres (herbal-greens) and aromatic ambers or woods—was disconnected from their advertising imagery (a 1984 Quorum ad shows a man in a suit lying on his side, his shadow that of a devil. The caption: ‘a cologne for the other man lurking inside you’). On my skin Quorum was the smell of forest walks, tobacco, and leather. If it reminded me of walks with my father, his pipes, razor strops and leather polish, it also became mine, something I can now only describe as the smell of thinking, as I would walk to school sniffing my wrist and considering what it was I wore. I knew full well that he knew I wore them and perhaps he never said anything because he wanted me to feel I had the right to take his scents and make them my own; an act of necessary theft rather than a gift which risked the burden of present lesson or future expectations.

So the idea of gender as a necessity of perfume fell away, just as it was beginning to in clothing—borrowing from both my mother’s store of kimonos and accoutrements as well as my father’s oversized sweaters and tweed blazers—and how I had long felt about my sexuality. The olfactory revelations of those morning walks and the realisation that my parents had unknowingly gender-swapped the stereotypes of minimal and more elaborate beauty rituals began to answer the questions and feelings I had long had as to why I ‘must’ be a certain type of person; both in dress and desire in the eyes of others. In an essay about the clothing designer Eileen Fisher, Janet Malcolm writes about some samples ‘the image … wafted out of them like an old expensive scent.’, as well as noting something of importance she reads in a Fisher brochure titled ‘Simply—To Be Ourselves’: ‘the underlying philosophy of our design—no constraints, freedom of expression.’3 That Fisher was influenced by the kimono in her simple designs reminded me that in design, perfume, and desire, there are simply elements: one takes those and becomes the person they wish to be in the world. To (re)create, manipulate, and distract from the norm; the magician’s smoke and sleight of hand.

As I learned more about the technical aspects and narratives of scent, gender, leather and smoke began to blur. According to Robert Piguet Parfums, Bandit was ‘based on a “Bad Boy” concept … Piguet shows featured models sporting villain masks and brandishing toy revolvers and swords.’4 Chanel’s Cuir de Russie scent was inspired by Coco’s lover the Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich.5 In 2000, Editions de Parfums Frederic Malle released Le Parfum de Therese, an until-then private fruity-leather 50s creation by the perfumer Edmond Roudnitska for his wife.6 Malle’s entire line is marketed as gender-free, but it is especially endearing that Therese is now for all. My father once expressed that he liked Guerlain Shalimar, but my mother would not wear it—a revelation of two parts: first, she had no desire to conform to someone else’s, especially as a young Japanese wife, and second, that Shalimar is a leather ‘oriental’ (rich in amber and/or other resins; here, opoponax and incense). Years into adulthood, I look at my ever-evolving collection and see that it still echoes my father’s cabinet: the smoky vetiver of Chanel Sycomore, powdery leather of Celine Reptile, the sweet tobacco of Boucheron Ambre d’Alexandrie. I prefer feminine scents with a touch of austerity, like the sombre mossy rose of Dior Gris Dior, or full-blown carnality, in the sunny fleshiness of Divine L’etre Aime Femme.

I recall a moment as barely a young adult, being asked with surprise by a female work colleague if I was wearing a men’s cologne. This was the (mostly) minimalist 90s, with Bvlgari Eau Parfumée Au Thé Vert, Issey Miyake L’eau d’Issey, and of course, CK One. I wore Halston Catalyst for Men, a rich herbal-leather warm with bay, nutmeg, and woods. I replied yes, to which she said with a laugh, ‘you would wear something like that!’, a compliment, but telling in that she adhered to a divide she would never cross or erase. Some time ago, I was sent a beautiful booklet by the perfume house Le Galion with descriptions of all their scents as well as vintage images. I smiled at the advertisement shown for Sortilège, a 1936 powdery aldehydic floral: featuring a beautiful Newton-esque model in a plunging black and white gown, chic black headwrap, diamonds and rubies, and glamorous makeup, the caption read: ‘Cette année, les femmes ressemblent à des femmes. C’est Sortilège leur parfum’ (roughly: ‘This year, women look like women. It’s their perfume Sortilège’). Perfume remains a state of skin and smoke, the division and blur where gender and ritual can play.

Tomoe Hill is not a writer, but in her words rather ‘someone who writes.’ She once studied philosophy at King’s College, London and is now at work on a book, tentatively called Songs for Olympia.

W Koestenbaum, My 1980s & Other Essays, FSG Originals, 2013. ↩

D Barthelme, Not-Knowing, Counterpoint, 1997. ↩

J. Malcolm, Nobody’s Looking at You, Text Publishing, 2019. ↩

ttps://robertpiguetparfums.co.uk/collections/classic-collection/products/bandit-eau-de-parfum ↩

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cuir_de_Russie ↩

https://www.fredericmalle.co.uk/product/19566/50136/perfume/le-parfum-de-therese/by-edmond-roudnitska ↩