SINCE THE RENAISSANCE, WESTERN fashion has integrated exotic dress practices associated with a spellbinding Orient. Madame de Pompadour’s Ottoman musings, Liberty’s textile imports and Paul Poiret’s cues from Ballets Russes – all flirtatious rag picking of orientalist dress – incorporated a sense of exotica into Western fashionable dress. Orientalism, and the related appellation orientalist, opens up to a wide debate on Western visions of the East, and has been used as an all-inclusive term to denote ‘the impact upon Western dress and fashions of the clothing and customs of oriental nations across many centuries; Turkish, Indian, Chinese and Japanese fabrics and forms of dress influenced Western ideas of design and construction’.1 When fashion’s orientalist interpretations are paired with risqué baring of flesh or distorting of the proportions of the body, it creates ambiguous and haunting images of otherness that trespass the loaded terrain between the shameful and the shameless.

When high fashion borrows from the Orient, it often engages in acts of reversal where, put simply, the bared and displayed body becomes covered and concealed. The ‘orientalised’ body whether it is seen as exotically fascinating, stereotyped as an ethnocentric myth of an all-encompassing East, or displayed as inferior in relation to Occidental ways of doings, releases a sense of ‘otherness’ and ‘difference’. Embedded in Orientalism, according to literary theorist Edward Saïd, are romanticised and simplified images, Western imperialist misrepresentations, of Asia and the Middle East. These often rest on Western domineering self-affirmation where the Orient ‘has helped to define Europe (or the West) as its contrasting image, idea personality, experience.’2

Orientalism in fashion straddles dichotomies of the covered and uncovered – and often stands at the crossroad of Western often skin-exposing fashion and traditional dress practices associated with modesty. What cultural theorist Stuart Hall calls ‘the spectacle of the “Other”‘3 refers to how representations of difference, here an ‘orientalised’ body, are stereotyped in the media. Hall charts how ‘difference’ and ‘otherness’ are approached through, among others, anthropological and psychoanalytical theories. The anthropological approach to understanding things is through giving them different positions of social classification. Classifying things, or organising them into binary oppositions, are significant acts of attributing meaning to them, such as the West and the East, culture and nature, good and bad. This also provides symbolic boundaries between things, which help one to understand their differences. Psychoanalysis has approached the concept of the other through the argument that ‘the “Other” is fundamental to the constitution of the self.’4 The idea is that one gains a concept of self, self-definition, through difference from others. Designers, consumers and the media often set up what Hall calls a ‘symbolic frontier between (…) “insiders” and “outsiders”, Us and Them.’5

These binary, often stereotyped, tensions remind us of the body’s unruly ammunition. While to uphold a distinction between the West and the East, inside and outside, us and them, is anachronistic, as global fashion moves freely across the world from the East to the West and vice versa, there is something interesting to be found in the brackish water of the melange. It is here we find the complexities of modesty and immodesty as well as concealment and exhibition played out. The idea that the undressed body somehow corrupts moral standard runs like a paradoxical vein throughout Western culture, as precisely the undressed body, or rather parades of fashionable flesh, is also endlessly exploited for its shock value. Nudity is everywhere both wicked and common. Not just Terry Richardson’s Gonzo-style photography and Vogue Paris’ porno chic pages, but also in wider culture we are bombarded with untiring images of exposed bodies that sell.

Exploring both the material and cultural functions of fashion, scholars have been preoccupied with these across practical functions, aesthetic or even moral qualities of clothes often arguing that the reasons why people wear clothes are based on protection, attraction, communication and modesty. Psycholoanalyst John Carl Flügel6 sought to understand fashion as a pendulum moving between modesty and eroticism with sex being repressed in civilised cultures. But what is deemed shameful and indecent by some cultures might be displayed with pride in others. The degree as to which the body and clothing are shamed is culture specific. Intrinsic to the work of many fashion scholars, and indeed to dress cultures, is how the body, as the structure of fashion, is civilised and cultured through adornment. Flesh on its own is simply less loaded.

There are numerous examples of this dialogue within high fashion, and often designers appropriate Orientalism as a potpourri of Otherness. Riccardo Tisci with his autumn/winter 2009 haute couture collection for Givenchy visited Berber tribes with drop-crotch trousers (which have been embraced by a variety of designers for many seasons), full-length skirts, hooded veils, draped transparency and jewelled headpieces. This was an aestheticised and romanticised take on Berber dress, adorning the Western body in connotations of ethnicity rather than releasing fashion’s omnipresent paradoxes of shame and shamelessness.

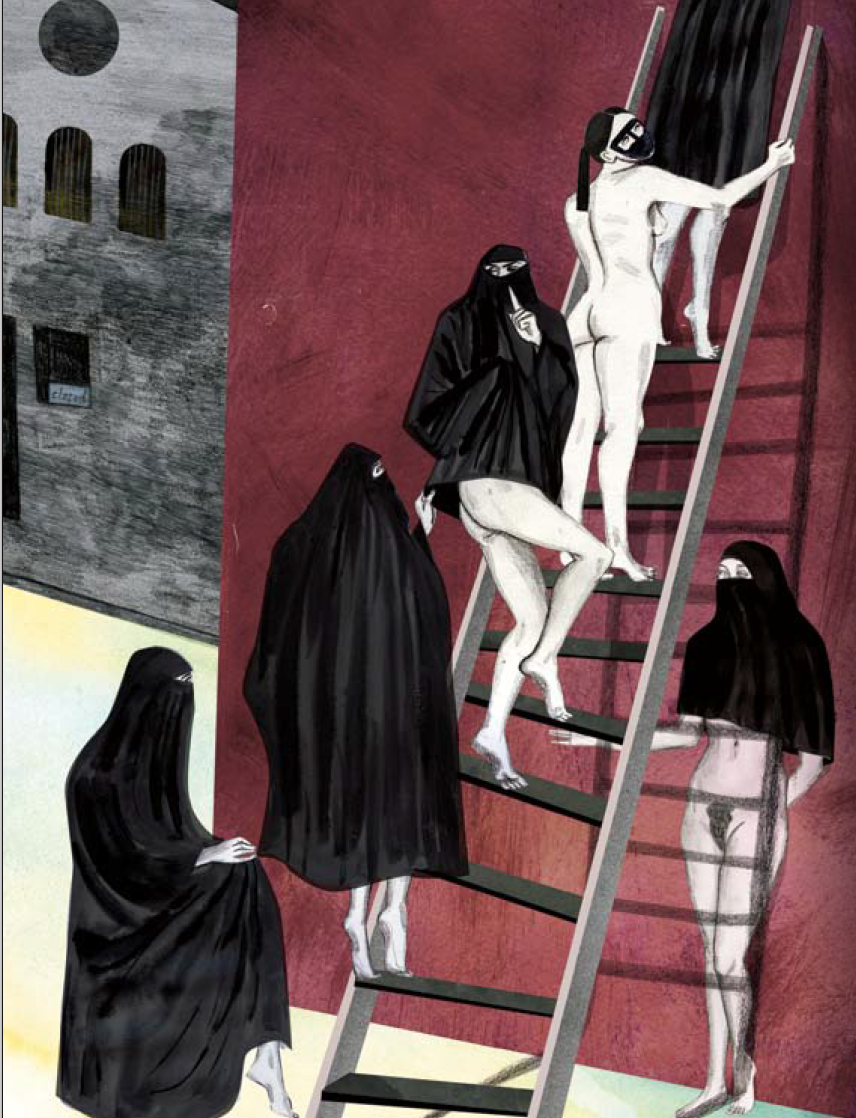

Different is Hussein Chalayan’s spring/summer 1998 ‘Between’ collection. Evoking Daniel Rabel’s enigmatic seventeenth-century painting ‘Première Entrée des Fantômes’ with four spectres clad in head-to-toe black cloth, Between casts a shadow of phantoms of extreme beauty on the screen of fashion. The finale of Chalayan’s show saw six models wearing black chadors of different lengths, from naked to totally covered – all of them with their faces covered. Like ‘nudes… wearing ghosts of absent clothes’7 the show can be seen as both spectacle and spectre, throwing up a range of complex issues around shameful eroticism, modesty dress and cultural identity.

The practices of veiling have a long and complex history throughout the Arab world, and whereas countries like Turkey have banned the veil, it has enjoyed a revival from the 1970s amongst Egyptian women as part of a wider Islamic movement.8 But covering is, of course, not a practice confined to Muslim modesty (as Reina Lewis argues elsewhere in this issue). Throughout the history of ‘Western’ and ‘Eastern’ dress practices, the distinction between dressed and undressed has been carefully guarded, and by now the exhaustive flaunting of flesh has somehow desexualised, overexploited and clichéd the body. Yet, it seems nudity triggers a certain consuming gaze, as the most private is made available to scrutinise without shame. According to Anne Hollander the nude in art was invented to both legitimise and idealise the otherwise profane nakedness.9 While Chalayan’s models are fashioned and idealised, and thus not naked, their nudity is uneasy precisely because they are also veiled – a dress practice widely associated with modesty. The juxtaposition of nudity and the veil is loaded with shock value and notions of sacrilege.

Across cultures we learn from a young age what parts of the body are shameful, and the genitals are certainly one of them. The Fall of Man, with Adam and Eve and the fig leaves, is one of the first examples to connect bodily exposure, more specifically the genitals, with shame and profanity. Vivienne Westwood explored the potency of this part of the body in 1989 with her fig leaf tights which instead of covering the genital area shamelessly drew attention to it. Chalayan’s veils of varying lengths similarly charge the sense of nakedness further and capitalise on its shock value.

Growing up in Cyprus, on the colliding frontier between the Muslim and the Christian world, implicit in Chalayan’s wider work is an anthological inquiry into cultural difference and identity, exploring cultural exiles, people without identity in shadowing no man’s land, inhabiting some sort of cultural transit in the interface of high technology and local ethnicity. The religious motif of ‘Between’ was a continuation of his previous collection ‘Scent of Tempests’ (autumn/winter 1997) which was an attempt to create attire for worship as Chalayan found it curious that ‘people who worship pray for bad things not to happen.’10 Further to Between’s obvious religious connotations, its transgressive power lies in questioning the issues of bodily identity, quite literally with ‘faceless’ models. Chalayan was exploring how through ‘the religious code you are depersonalised’,11 and in doing so making yet another curious link between fashion, religion and identity. Chalayan is not singular in denying his models faces – Maison Martin Margiela has also utilised this to lengths. Surrealist photographers, like Man Ray and Blumenfeld, also embraced Freud’s theories and used masks to play with hidden, dreamlike identities. Chalayan’s collection not only comments on the seemingly replica identity of models, reducing them to mere unidentifiable, depersonalised bodies rendered by the veil, it also casts light on fashion’s aggressive exposure of flesh and its worship of identity.

Chalayan’s ‘Between’ elicits questions about cultural melange and the exposure of seemingly binary dress practices where the body is equally, if not shamed, then exposed as an ideological site of identities in motion. As such, the collection treads a loaded territory of the veiled, faceless, unidentified women and their exposed bodies. It renders visible both Western and Eastern approaches to the body and in doing so mirrors the other, becoming the spectacle of the Other. The concealed becomes the shadow side of the exposed, and vice versa, and herein lies the dynamics of the collection, exaggerating two inextricably linked approaches to the body – exposure and concealment – which is the core dynamics of fashion.

Another bodily representation of otherness is present in Comme des Garçons’ spring/summer 1997 ‘Dress Becomes Body, Body Becomes Dress’ collection where tight-fitted, transparent dresses with asymmetrical ‘tumour piece’12 padding made for unorthodox, almost alien bodies. Across dress and fashion history there are various examples of bodily alterations and augmentations, such as foot binding, cod pieces, neck rings, corsets and crinolines. Protruding stomachs seem particularly peculiar to contemporaneous eyes – such as the male peascod bellies of the sixteenth century – most famously represented by Jan Van Eyck’s 1434 painting of the Arnolfinis. A normative fashioned body streamlined in proportion is absent, and ‘Dress Becomes Body, Body Becomes Dress’ instead gives way to a transformed, almost pathological body, evoking the shamed hunchback and the leper wrapped in fabric. While this grotesque body may be uneasy, it is, as fashion curator Harold Koda notes, ‘nowhere near the exaggerated scale of the panniered gowns that were in vogue in the eighteenth century.’13 Kawakubo’s Japanese background affects her sense of aesthetics and also the way she approaches the body. In traditional Japanese society, sexuality is never revealed explicitly,14 and Kawakubo argues that her take on the body is ‘different from the pleasure Western women take in showing the shapes of their bodies. It bothers Japanese women… to reveal their bodies’.15 Indeed, the underlying body in her wider work is different, and more enigmatic, to the exposed and sexualised body so often present in ‘traditional’ Western fashion. Instead the collection’s morphed, disproportioned form seems a carnivalesque, if not shameless, suggestion of a different body.

Shame is the shadow of fashion. Bodies and aesthetics not immediately performing to the ideal template of the time are so often consumed by a fashion system that instead internalises and reworks them into shameless reversals. Big bellies, disproportioned hips and, of course, exposure of pubic hair are but a few features considered disgraceful – albeit they are part of the very human body. Perhaps it is when fashion casts light on what is deemed human flaws, the imperfect, that we understand that ‘bodies are potentially disruptive’.16 The work of Chalayan and Kawakubo provide us with a symbolically different perspective through which we fundamentally understand both our own body and the system of fashion. It is through such work that we come to understand fashion’s ability to make visible and capitalise on complex cultural values.

Dr Ane Lynge-Jorlén is an independent Copenhagen-based fashion reseacher and curator, and a former editor of Vestoj.

Emma Löfström is a Stockholm-based artist and illustrator.

This article was originally published in Vestoj On Fashion and Shame.

‘Orientalism.’ The Berg Fashion Library, (n.d.). (accessed 13 Nov. 2011 ↩

E Saïd, Orientalism. Vintage Books, New York, 1978. pp. 1-2. ↩

S Hall (ed), Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices, Sage, London, 1997, p. 225. ↩

4. Ibid. p. 237. ↩

Ibid. p. 258. ↩

J. C. Flügel, The Psychology of Clothes, AMS Press, New York, 1976. ↩

A Hollander, Seeing Through Clothes, Viking, New York, 1978, p. 86. ↩

F El Guindi, “Veiling Resistance”, Fashion Theory: The Journal of Dress, Body & Culture, 3 (1). 1999, pp. 51–80. ↩

A Hollander, Seeing Through Clothes, Viking, New York, 1978. ↩

P Golbin, ‘A Synoptic Guide to Hussein Chalayan’s Mainline Collections 1993-2011’, Hussein Chalayan, Rizzoli, New York, 2011, p. 271. ↩

Ibid. ↩

P Golbin, ‘A Synoptic Guide to Hussein Chalayan’s Mainline Collections 1993-2011’, Hussein Chalayan, Rizzoli, New York, 2011, p. 271. ↩

Ibid. ↩

C Evans, ‘Paris 1996’, 032C, issue 4, 2002/2003, pp. 82-83. ↩

H Koda, Extreme Beauty: The Body Transformed, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2001, p. 113. ↩

J Entwistle, The Fashioned Body, Polity Press, Cambridge, 2000, p. 8. ↩