‘I think my roof needs a little repairing too! Please send him (:’

‘Damn, Tony looks like he could be a D&G model. Que guapo!’

‘I think my electric cables are broken…’

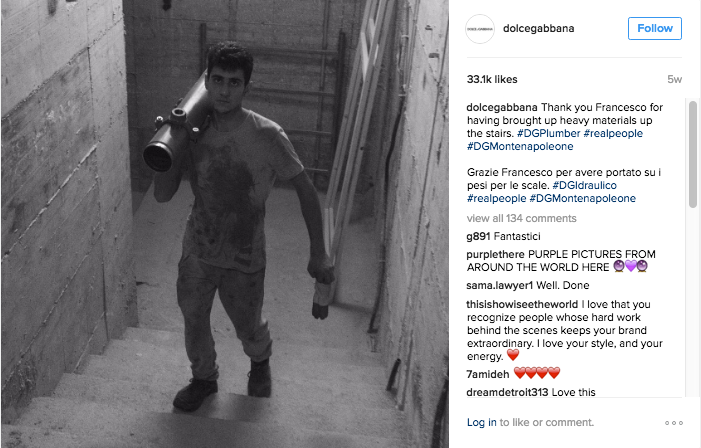

THESE ARE INSTAGRAM COMMENTS below black and white images of workers being ‘real men’ – building, plastering, carrying heavy weights, fixing things or more generally just getting their hands dirty. Some of them in tight T-shirts, some of them shirtless. One of them looks directly at the camera, aware that he is being looked at. The caption says ‘thanks you for the hard work,’ followed by a hashtag, #realpeople. Things get even more real – pun intended – as each worker has been dutifully branded: #DGPlasterer, #DGElectrician, #DGPlumber and so on. This is a Dolce & Gabbana social media campaign, designed to promote the opening of the brand’s new flagship store in Milan’s über-fashionable Via Montenapoleone – an area where such ‘real’ people are arguably hard to come by. An Instagram user seems rather perplexed: ‘Lol they call him “real people” what do “un-real people” look like or behave like?’

Do not fear; Stefano Gabbana and Domenico Dolce are not quitting fashion for documentary photography. They have just taken one further step in the inclusion of ‘real’ people – non-models – in their advertising campaigns. Only this time it is not cute Sicilian grandmothers or an exotic bullfighter, but rather working-class men and used as props in the never-ending quest to sell more handbags, perfumes and shoes.

The photographs seem to celebrate the human component behind the perhaps less-than-real architecture of capitalistic desire, but may in fact elicit the opposite response. The reality of the workers is literally filtered – most likely through Instagram’s Inkwell – and turned into a black and white fantasy reminiscent of Herb Ritts’ male portraits. Dolce & Gabbana is famous for this visual approach, as its underwear campaigns and the D&G coffee table book Uomini (‘Men’) show. Behind these images of ‘real’ people is a not-so-subtle invitation to eroticise the workers, their bodies, their performance of ‘real’ masculinity. It unintentionally brings to mind Elizabeth Hurley’s classist use of the term ‘civilians’ for non-celebrities on Larry King Live in 2000.1 The hashtag #realpeople implies a distance, both erotic and social: they are ‘real’ people, we are not; this is ‘real’ work, ours is not.

Another step towards the marketing of the ‘real’ is the brand’s autumn/winter 2016-17 advertising campaign, which portrays models catapulted in the streets of Naples, where they wander around the city and interact with locals. The ‘real’ people pictured in D&G’s autumn/winter 2016-17 campaign are locals and passersby that happened to be on location on the day of the shoot. The campaign was ‘meant to bring fashion to the people’ and depict ‘real life,’ according to the designers.2 The idea of spontaneity also dictated the choice of working with Franco Pagetti, a war photographer, who was convinced to shoot the campaign after the designers reassured him with the words: ‘We don’t give a damn about fashion. Who cares about clothes and glossy images. We want photos that are real, emotional, authentic.’3 And who better to capture reality than a war photographer? Indeed, some reality managed to sneak into the images. Bags from rival brands like Armani and Givenchy show in the images, for instance – as an effort to preserve the spontaneity of Pagetti’s approach, according to Gabbana. But as observed by a fashion commentator, ‘next to the rich, highly adorned D&G looks … everything else looks pretty blah.’4 This means not only that the D&G products look desirable in comparison to those by other brands, but also that the clothes worn by the ‘real’ people in the campaign, and therefore by extension their bodies and their visual presence, look ‘pretty blah’ too. The consumers are invited to look at drab ‘real’ people next to fashionable, desirable Dolce & Gabbana products – so much for not giving a damn about fashion.

The dynamic between the models and the passers-by suggests the temporary meeting of two worlds apart, in which the gaze once again plays a key role. On the one hand, the foreign, rather awkward look of the designers and the richly adorned models – emblems of global modernity – onto the locals; on the other, the look of the locals onto the alien creatures who suddenly appeared in their familiar landscape. In both cases, a traditional heteronormative gaze. Male models are shown as dominant; they actively interact with the locals, bond with other men and flirt with older women. Female models, on the other hand, appear to be rather overwhelmed by the interactions. One of the images shows the only black model in the campaign walking down the street, seemingly embarrassed as men look at her and one even claps behind her. Is this supposed to be what ‘real’ men do? Perhaps yes, according to the designers. ‘Boys will be boys!’ seems like an accurate description of the brand’s historical reliance on tropes of hyper-masculinity like ‘the Latin lover.’ ‘Real’ people and ‘real’ men, then, come from the post-war Italy of La Dolce Vita. ‘It is still like the 1950s here, in a way,’ stated the designers on Facebook referring to Naples.5 The reality they present is orchestrated through the choice of location and further mediated by a nostalgic gaze. This time, the feeling is of a social and temporal distance.

Ultimately, the emphasis on the ‘real’ in Dolce & Gabbana’s advertisements and social media campaigns originates in a preoccupation with authenticity, which for them is to be found in specific places and people: workers, Napolitans, Sicily, the monolithic Italian family. They all become marketable symbols of craftsmanship and tradition that the D&G brand story relies on. The authenticity is, however, heavily curated – it feels more like an episode of Keeping Up With the Kardashians than a photograph by Nan Goldin. ‘Dolce & Gabbana is the banner label of reality TV. Bling, brevity, bra straps, Beckhams,’ observed a fashion journalist in 2005.6 The brand has been attempting to rewrite its story, from reality TV bling to romanticised fantasy of ‘Italianness,’ arguably to facilitate its transition from ‘legitimacy’ to ‘heritage.’7 The pressure is arguably even stronger in countries with a strong cultural identity like Italy, where brands like Gucci, Ferragamo, Armani and Prada have respectively taken steps to ensure their status as heritage brands through archives, museums, foundations and publications. Dolce & Gabbana, perhaps realising its slight delay in the race for heritage status, seems to have strengthened its marketing strategy by resorting to the banner of the ‘real’ as a way to create a direct, emotional connection with the people who supposedly inspire the designers. Ultimately, however, the attempt to integrate ‘real people’ in its promotional campaign echoes other questionable attempts to pay homage to those with lower or non-existent social status, much like John Galliano’s controversial homeless-inspired collection for Dior in 2000. These campaigns fall into a trap that fashion is already way too familiar with: an effort to separate itself from the ‘real’ through a sellable fantasy, which in turn relies on the commodification of the real itself. None of these ‘real people’ could actively partake in, and much less buy into, Dolce & Gabbana’s ‘real’ world. So while the brand’s marketing strategy aims to be a fresh take on heritage branding, it has ironically succeeded in communicating the outdated policy that high fashion and ‘stuffy’ museology share: ‘you can look but you can’t touch.’

Alex Esculapio is a writer and PhD student at the University of Brighton, UK.

http://transcripts.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/0010/20/lkl.00.html ↩

M Romani, ‘D&G: umanità e bellezza, chi se ne frega della moda,’ la Repubblica, 19 June 2016, http://www.repubblica.it/venerdi/articoli/2016/06/09/news/umanita_e_bellezza_chissenefrega_della_moda-141658616/ ↩

Ibid. (my translation) ↩

A Vingan Klein, ‘Dolce & Gabbana Features the People of Naples (and Other Brands) in Fall 2016 Campaign,’ Fashionista.com, 14 June 2016, http://fashionista.com/2016/06/dolce-and-gabbana-fall-2016-campaign ↩

Ibid. ↩

L Armstrong, ‘The guys who got the girls to get their bras out,’ The Times, 20 May 2005 ↩

E Corbellini & S Saviolo, Managing Fashion and Luxury Companies, Rizzoli ETAS, 2012 ↩