Clothes were a major cause of rows, naughtiness, misery and all unpleasantness, right through my whole youth. The difficulties were caused, not only by best clothes, but by practically everything we wore.

In her own way my mother took a good deal of trouble about dress, not only about her own, but about ours, too. She used to spend hours and hours superintending a humble daily dressmaker in cutting old dresses to pieces, and putting them together again in new permutations and combinations; for that marble-hearted fiend Economy, who was her evil angel, was always putting in his spoke and preventing her from having things made at a good shop. Sometimes the results of this home manufacture were rather clumsy; but as far as my mother was concerned it really did not matter much, as she always managed to look attractive, even if it were in spite of, rather than because of, her dress. For one thing she had a very fair idea of what became her; she never wore those dreadful hard boater hats, when they were so fashionable; and she knew that soft floppy things suited her better than tailor-made suits. She was in her glory in a ‘tea-gown’; or in a summer dress, with a feather boa, ostrich-plume hat and parasol.

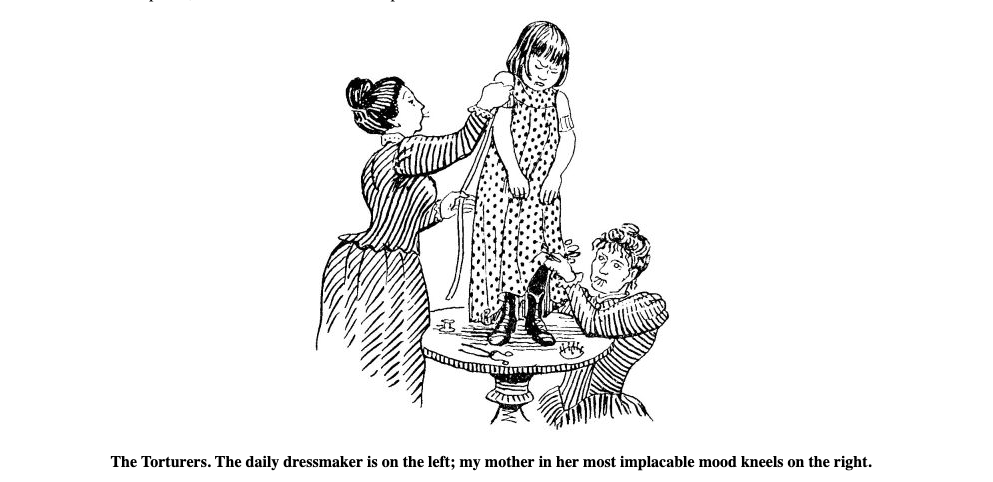

My share of the dressmaking industry was the unpicking of the old dresses, which I did most unwillingly. Sometimes, when it went on for too long, Good God, there was such a scene! But even that was not so bad as when I had to try on a new frock myself. It seemed to me then that I was kept standing on the table for whole days at a time (I suppose it may have been about twenty minutes), while she and the dressmaker fumbled about, with their mouths full of pins; cutting with ice-cold scissors against my bare neck, and constantly saying: ‘Now please stand up straight for a minute’; or ‘For Goodness’ sake do keep still’; until at last there was a real explosion.

Once, when I could not endure it a single instant longer, I went completely mad and, seizing between my teeth the pink cotton frock they were fitting on, I bit it all to pieces. I suppose I was punished for this, but I cannot remember anything except my triumphant satisfaction in my crime. Another time I fairly liquidated a hat. My mother had brought back some hats for us from Paris. They had yellow straw crowns and frilly white paper brims, and were supposed to look like daisies. After an argument, one Sunday morning, Margaret and I were made to go to King’s Chapel wearing them, and a sulkier pair of daisies you never saw. But once inside, and safe in the stalls—for Walter the Verger always put us in the High Places, though we really had no connection with King’s—once safe inside, I say, where grown-up reactions had all to be put into cold storage and their human accounts were frozen…. I took off my hat and STOOD on it, and squashed it as flat as ever St. George squashed the Dragon; and no one could ever wear it again. Glory, glory hallelujah.

For, in spite of my mother’s efforts, I thought all my clothes horrible. I can’t remember liking a single coat or hat or frock in all my youth, except for one pinafore with pink edges. There is a theory that we always admire the present-day fashions, and think those which are recently past vulgar, till lapse of time gives them a period romance again. This cannot always be true; for I certainly thought that the dresses my mother had worn in the ‘eighties were rather charming, while all the fashions from 1890 till 1914 seemed to me then, and seem to me still, preposterous, hideous and uncomfortable.

I remember, when I was at school in 1902, walking at the back of our Sunday crocodile, and seeing all the girls in front of me, very smart and Sundayfied, going down the hill to church. And I thought (I am afraid, with a touch of superiority): ‘How frightful they all look, and what a lot of trouble they have taken to make themselves still more frightful. I am sure I look every bit as hideous, but at any rate I haven’t taken any trouble about it at all.’ I thought them much ‘the worse for dress,’ as Uncle Lenny once said of an over-dressed lady of his acquaintance. The thought comes back to me perfectly clear, every time I get a whiff of something which reminds me of the empty, damp, suburban, Sunday-morning smell of Wimbledon Common; and then I see again their beribboned top-heavy hats, stuck on to the top of the hair they had spent so long in frizzling and puffing out; and their tightly corseted, bell-shaped figures wobbling down the hill, as they chattered their way to church.

I suppose that, in spite of the fashions, there must have been some elegant women in the ‘nineties; but even if any of them lived in Cambridge (which is doubtful) we should certainly have failed to appreciate them. Cambridge was not well-dressed; Darwins were far from smart; and we cousins despised, or affected to despise, dress. Four of us really did, largely because our clothes were imposed on us from above, without even the power of veto. Frances alone had a secret wish to be prettily dressed; but she had to pretend to be above such things; for interest in clothes showed a low moral nature. Whenever we were telling stories, if the story-teller said: ‘She was a very fashionable lady,’ we all knew at once that she was the villainess of the piece.

In a less explicit way this was the attitude to dress of all born Darwins, and of most of the married-in Darwins, too. Dressing well was a Duty, and not a pleasure: your duty to that state of life to which it had pleased God to call you. Dresses designed solely with an eye to the wearer’s age and position are apt to be rather serious affairs; but at any rate every aunt managed to look extremely dignified in one of her ‘best gowns.’ Aunt Ida always looked like a duchess, anyhow—one of the best kind of duchesses of the real old aristocracy; and Aunt Etty was magnificent on occasion. Her dresses were beautiful, too, even in that unpromising age, and her little lace caps were charming. As always, she made her position perfectly clear; she would say: ‘I shall wear my pearl necklace and then they’ll know that I’ve done my best.’ White gloves were also a sign that one was doing one’s best.

My mother, on the other hand, frankly enjoyed dress. She tells in a letter how she set out to pay some visits, ‘George in his high hat, which he only wears in London and Paris, and I in my red cloth. We both went off feeling very comfortable in our best clothes. Clothes do give you assurance, there is no doubt about it.‘ There, in a nutshell, lies the difference between her and me. For she could never have believed that this feeling was entirely unknown to me. Nor, with the best intentions in the world, did she understand that I needed very special treatment to be made tolerable; that what suited her, did not suit me.

Once, when I was about eighteen, I was made into a fat, blue-satin bridesmaid for a cousin’s wedding. It is really astonishing that I did not cast a curse over that bridal pair, such were the blackness and venom of my feelings in the church. However, the marriage has been a success, in spite of this inauspicious opening. But I can here and now lay my hand on my heart and say that I always—when I thought about it—felt a great ill-dressed lump; and when I went to boarding-school, and they all despised me, I thought they were perfectly right. In a sort of way that is; for I simultaneously thought them quite wrong, about appearances in general.

My clothes were particularly unsuccessful just then. I had a new green tweed coat and skirt, badly made by the poor little daily dressmaker; and the skirt had been lined with bright buttercup-yellow cotton, which showed round the edges whenever I moved. This was because, at the Christmas party that year, there had appeared an enormous yellow pumpkin, which suddenly split open to reveal Billy and all the Christmas presents inside it; and so my mother had economically used up the pumpkin material to line my skirt.

I endured the criticisms of the girls at school for some time—and girls are very outspoken about such matters—but at last I turned at bay. I simply made up my mind that as I could not be good-looking or well-dressed, I would never again think about my appearance at all. I would have enough clothes to be decent, but I would try to be as nearly invisible as possible, and would live for the rest of my life like a sort of disembodied spirit. Of course I knew that this was not the best possible solution, but it was the only one that seemed to me practicable. And at any rate this decision did really set me free; I hardly ever thought about my clothes or my looks any more at all; and, except sometimes at the beginning of a party, nearly always forgot to be self-conscious.

This is the first part of Gwen Raverat’s memoir, first published in 1952. Raverat (1885-1957) was a wood engraver, and a founder of The Society of Wood Engravers. She was also the granddaughter of Charles Darwin. In the preface of her book, Raverat writes: This is a circular book. It does not begin at the beginning and go on to the end; it is all going on at the same time, sticking out like the spokes of a wheel from the hub, which is me.